- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

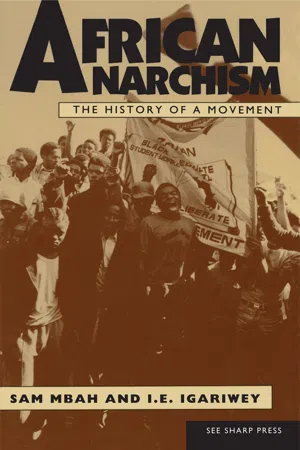

About this book

African Anarchism covers a wide range of topics, including anarchistic elements in traditional African socieites, African communalism, Africa's economic and political development, the lintering social, political, and economic effects of colonialism, the development of "African socialism, the failure of "African socialism, and a possible means of resolving Africa's ongoing crises.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

1

What Is Anarchism?

Anarchism as a social philosophy, theory of social organization, and social movement is remote to Africa—indeed, almost unknown. It is underdeveloped in Africa as a systematic body of thought, and largely unknown as a revolutionary movement. Be that as it may, anarchism as a way of life is not at all new to Africa, as we shall see. The continent’s earliest contact with European anarchist thought probably did not take place before the second half of the 20th century, with the single exception of South Africa. It is, therefore, to Western thinkers that we must turn for an elucidation of anarchism.

Anarchism derives not so much from abstract reflections of intellectuals or philosophers as from the objective conditions in which workers and producers find themselves. Though one can find traces of it earlier, anarchism as a revolutionary philosophy arose as part of the worldwide socialist movement in the 19th century. The dehumanizing nature of capitalism and the state system stimulated the desire to build a better world—a world rooted in true equality, liberty, freedom and solidarity. The tyrannical propensities of the state—any state—underpinned by private capital, have propelled anarchists to insist on the complete abolition of the state system.

The New Encyclopaedia Britannica1 (15th Edition) characterizes anarchism as a social philosophy “whose central tenet is that human beings can live justly and harmoniously without government and that the imposition of government upon human beings is in fact harmful and evil.” Similarly, The Encyclopedia Americana2 (International Edition) describes anarchism as a theory of social organization “that looks upon all law and government as invasive, the twin sources of nearly all social evils. It therefore advocates the abolition of all government as the term is understood today, except that originating in voluntary cooperation.” Anarchists, it goes on to say, do not conceive of a society without order, “but the order they visualize arises out of voluntary association, preferably through self-governing groups.” For its part Collier’s Encyclopedic3 conceives anarchism as a 19th-century movement “holding the belief that society should be controlled entirely by voluntarily organized groups and not by the political state.” Coercion, according to this line of reasoning, is to be dispensed with in order that “each individual may attain his most complete development.” As far as definitions go, these lend some useful, if superficial, insights into anarchist doctrine. But their usefulness in the elucidation of the rich and expansive body of thought known as anarchism is patently limited. The wide gamut of anarchist theory is revealed only in the writings of anarchists themselves, as well as in the writings of a few nonanarchists.

According to Bertrand Russell, anarchism “is the theory which is opposed to every kind of forcible government. It is opposed to the state as the embodiment of the force employed in the government of the community. Such government as anarchism can tolerate must be free government, not merely in the sense that it is that of a majority, but in the sense that it is assented to by all. Anarchists object to such institutions as the police and the criminal law, by means of which the will of one part of the community is forced upon another part…. Liberty is the supreme good in the anarchist creed, and liberty is sought by the direct road of abolishing all forcible control over the individual by the community.”4

Russell justifies the anarchist demand for the abolition of government, including government by majority rule, writing, “it is undeniable, that the rule of a majority may be almost as hostile to freedom as the rule of a minority: the divine right of majorities is a dogma as little possessed of absolute truth as any other.”5

Likewise, anarchism is irreconcilably opposed to capitalism as well as to government. It advocates direct action by the working class to abolish the capitalist order, including all state institutions. In place of state/capitalist institutions and value systems, anarchists work to establish a social order based on individual freedom, voluntary cooperation, and self-managed productive communities.

Toward this end, anarchism posits that every activity currently performed by the state and its institutions could be better handled by voluntary or associative effort, and that no restraint upon conduct is required because of the natural tendency of people in a state of freedom to respect each other’s rights.

Anarchists are so implacably opposed to the state system and its manifestations that one of the founding fathers of anarchism, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, proclaimed: “Governments are the scourge of God.” Mikhail Bakunin elaborated on Proudhon’s propositions, explaining the goal of anarchism as the full development of all human beings in conditions of liberty and equality:

It is the triumph of humanity, it is the conquest and accomplishment of the full freedom and full development, material, intellectual and moral, of every individual, by the absolutely free and spontaneous organization of economic and social solidarity as completely as possible between all human beings living on the earth.6

Bakunin goes on to say that “we understand by liberty, on the one hand, the development, as complete as possible, of all the natural faculties of each individual and, on the other hand, his independence, not as regards natural and social laws but as regards all the laws imposed by other human wills, whether collective or separate…. What we want is the abolition of artificial privilege, legal, official influences.”7

Such privileges are necessarily the prerogative of the state. And thus Bakunin characterizes the state as nothing but domination, oppression, and exploitation, “regularized” and “systematized”:

The state is government from above downwards of an immense number of men, very different from the point of view of the degree of their culture, the nature of the countries or localities that they inhabit, the occupation they follow, the interests and the aspirations directing them—the state is the government of all those by some or other minority; this minority, even if it were a thousand times elected by universal suffrage and controlled in its acts by popular institutions, unless it were endowed with the omniscience, omnipresence and omnipotence which the theologians attribute to God, it is impossible that it could know and foresee the needs or satisfy with an even justice the most legitimate and pressing interests in the world. There will always be discontented people because there will always be some who are sacrificed.8

As Bakunin further observes, the state was an historically necessary evil, but its complete extinction will be, sooner or later, equally necessary. He repudiates all laws, including those made under universal suffrage, arguing that freedom does not mean equal access to coercive power (i.e., government via “free” elections), but rather that it means freedom from coercive power—in other words, one becomes really free only when, and in proportion as, all others are free.

It is Peter Kropotkin, however, who provides both systematic and penetrating insight into anarchism as a practical political and social philosophy. In two seminal essays, Anarchism and Anarchist Communism, he declares that the private ownership of land, capital and machinery has had its time and shall come to an end, with the transformation of all factors of production into common social property, to be managed in common by the producers of wealth. Under this dispensation, the individual reclaims his/her full liberty of initiative and action through participation in freely constituted groups and federations, that will come to satisfy all the varied needs of human beings. “The ultimate aim of society is the reduction of the functions of government to nil—[that] is, to a society without government, to Anarchy.”9

He elaborates:

You cannot modify the existing conditions of property without deeply modifying at the same time the political organization. You must limit the powers of government and renounce parliamentary rule. To each new economical phase of life corresponds a new political phase. Absolute monarchy—that is, court-rule—corresponded to the system of serfdom. Representative government corresponds to capital-rule. Both, however, are class-rule.

But in a society where the distinction between capitalist and laborer has disappeared, there is no need of such a government; it would be an anachronism, a nuisance. Free workers would require a free organization, and this cannot have another basis than free agreement and free cooperation, without sacrificing the autonomy of the individual to the all-pervading interference of the state. The no-capitalist system implies the no-government system. Meaning thus the emancipation of man from the oppressive power of capitalist and government as well, the system of Anarchy becomes a synthesis of the two powerful currents of thought which characterize our century.10

Kropotkin posits that representative government (democracy) has accomplished its historical mission to the extent that it delivered a mortal blow to court-rule (absolute monarchy). And since each economic phase in history necessarily involves its own political phase, it is impossible to eliminate the basis of present economic life, namely private property, without a corresponding change in political organization.11 Conceived thus, anarchism becomes the synthesis of the two chief desires of humanity since the dawn of history: economic freedom and political freedom.

An excursion into history reveals that the state has always been the property of one privileged class or another: a priestly class, an aristocratic class, a capitalist class, and, finally, a bureaucratic (or “new”) class, as in the Soviet Union and China. The existence of a privileged class is absolutely necessary for the preservation of the state. “Every logical and sincere theory of the state,” Bakunin asserts, “is essentially founded on the principle of authority—that is to say, on the eminently theological, metaphysical and political idea that the masses, always incapable of governing themselves, must submit at all times to the benevolent yoke … which in one way or another, is imposed on them from above.”12

This phenomenon is the virtual equivalent of slavery—a practice with deep statist roots. This is illustrated by the following passage from Kropotkin:

We cry out against the feudal barons who did not permit anyone to settle on the land otherwise than on payment of one quarter of the crops to the lord of the manor; but we continue to do as they did —we extend their system. The forms have changed, but the essence has remained the same.”13

Bakunin expresses this thought even more poignantly:

Slavery can change its form and its name—its basis remains the same. This basis is expressed by the words: being a slave is being forced to work for other people—as being a master is to live on the labor of other people. In ancient times as today in Asia and Africa, slaves were simply called slaves. In the Middle Ages, they took the name of “serfs,” today they are called “wage-earners.” The position of the latter is much more honorable and less hard than that of slaves, but they are nonetheless forced by hunger, as well as by the political and social institutions, to maintain by very hard work the absolute or relative idleness of others. Consequently, they are slaves. And, in general, no state, either ancient or modern, has ever been able, or ever will be able, to do without the forced labor of the masses, whether wage-earners or slaves.”14

The primary distinguishing factor between the wage worker and the slave is, perhaps, that the wage worker has some capacity to withdraw his or her labor while the slave cannot.

G. P. Maximoff does not see things any differently. To him, the essence of anarchism consists of the abolition of private property relations and the state system, the principal agent of capital. He states that “capitalism in its present stage has reached the full maturity of imperialism … beyond this point, the road of capitalism is the road of deterioration.”15

But capitalism is not alone here. Marxist state socialism as expressed in the former Soviet Union, from its very inception, provided ample evidence for the anarchist argument. Says Maximoff:

The Russian Revolution … revealed the nature of state socialism and its mechanism, demonstrating that there is no great difference in principle between a state so...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1. What is Anarchism?

- 2. Anarchism in History

- 3. Anarchistic Precedents in Africa

- 4. The Development of Socialism in Africa

- 5. The Failure of Socialism in Africa

- 6. Obstacles to the Development of Anarchism in Africa

- 7. Anarchism’s Future in Africa

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access African Anarchism by Sam Mbah,Chaz Bufe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Anarchism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.