eBook - ePub

An Understandable Guide to Music Theory

The Most Useful Aspects of Theory for Rock, Jazz, and Blues Musicians

- 74 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Understandable Guide to Music Theory

The Most Useful Aspects of Theory for Rock, Jazz, and Blues Musicians

About this book

This guide explains the most useful aspects of theory in clear, nontechnical language. Areas covered include scales (major, minor, modal, synthetic), chord formation, chord progression, melody, song forms, useful devices, (ostinato, mirrors, hocket, etc.), and instrumentation. It contains over 100 musical examples.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Scales

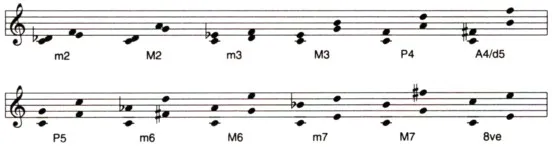

All scales and chords are simply patterns of intervals, and intervals are simply the distances between notes. They are measured in “steps.” The distance between adjacent white and black keys on the piano, or adjacent frets on the guitar, is one half-step. The distance between two white keys separated by a black key, or two frets separated by another, is a whole step. All intervals have names corresponding to the distance between the notes in them.

| Table 1 | ||

| Distance Between Notes | Interval | Abbreviation |

| ½ step | minor 2nd (semitone) | m2 |

| 1 step | Major 2nd (whole tone) | M2 |

| 1½ steps | minor 3rd (Augmented 2nd) | m3, A2 |

| 2 steps | Major 3rd | M3 |

| 2½ steps | Perfect 4th | P4 |

| 3 steps | Augmented 4th, diminished 5th (tritone) | A4, d5 |

| 3½ steps | Perfect 5th | P5 |

| 4 steps | minor 6th (Augmented 5th) | m6, A5 |

| 4½ steps | Major 6th | M6 |

| 5 steps | minor 7th (Augmented 6th) | m7, A6 |

| 5½ steps | Major 7th | M7 |

| 6 steps | Octave | 8ve |

The following musical example shows intervals as distances from middle C to notes above it, and between notes selected at random.

Example 1

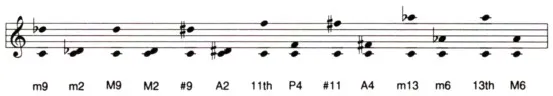

The names for intervals wider than an octave are found by moving the upper note down an octave and adding the resultant interval to the number seven (not eight). For example, the interval from middle C to Db above high C would be a minor 9th (7 plus a minor 2nd).

Example 2

These are the only intervals normally referred to in the octave-plus range; the other notes above an octave—10th, 12th, and 14th—duplicate notes already present as the 3rd, 5th, or 7th in most chords with members (notes) more than an octave above their roots. It’s also worth noting that there is more than one way to refer to many of these intervals. Beyond the octave, it’s probably more common to refer to intervals containing sharped or flatted notes as “sharp” or “flat” rather than “augmented” or “minor.” So, for example, a flat 9th (or ♭9, or flatted 9th) is the same as a minor 9th, and a sharp 9th (or ♯9) is the same as an augmented 9th.

Don’t be frightened by all of these intervals; their names are simply a convenient form of musical shorthand which musicians use to make communicating with each other easier. If you spend much time with other musicians, you’ll get used to hearing and using these interval names in short order.

Major Scales

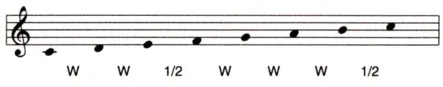

The most familiar scale is the major scale, do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-ti-do. The easiest way to the think of the major scale (C major in this case) is as the white keys of the piano, with the scale beginning and ending on C.

The distances between the notes in the C major scale are not equal. The notes E and F (the third and fourth degrees—notes—of the scale) and B and C (seventh and first degrees) are adjacent on the piano, while all of the other notes in the scale have a black key between them. The distance from E to F and from B to C is a half-step, or minor 2nd; the distance between the other notes in the scale is a whole step, or major 2nd.

Example 3

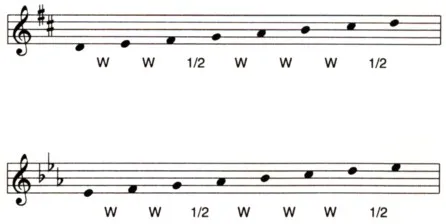

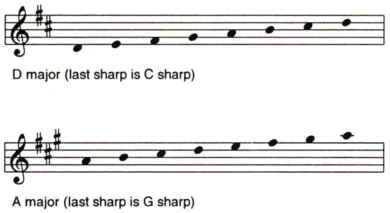

All other major scales have the same arrangement of whole steps and half-steps as the C major scale. Here are two examples, the D major and E♭ major scales:

Example 4

At this point you might be wondering how you can figure out where the major scale starts in various key signatures. The easiest way in sharp key signatures is to remember that the major scale starts a half-step above the last sharp (the sharp farthest to the right). So, for example, when the last sharp is C♯, the key is D major, and when the last sharp is G♯, the key is A major.

Example 5

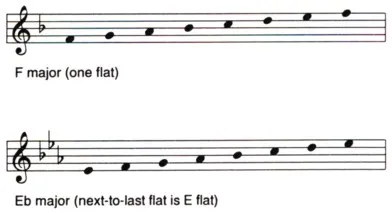

The procedure is almost as simple with flat key signatures. When only one flat is present in the key signature, that key signature is F major—in other words, the major scale begins and ends on F. When more than one flat is present, the key signature is that of the next-to-the-last flat to the right. So, for example, when the next-to-the-last flat is E♭, the key is E♭ major, and when the next-to-the-last flat is D♭, the key is D♭ major.

Example 6

And, of course, when no flats or sharps are present, the key is C major.

Minor Scales

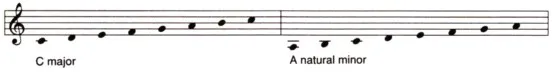

After the major scale, the next most common type of scale is the minor scale. There are three common forms of the minor scale. The simplest is the natural minor, which uses the same notes as the major scale, but which begins and ends on a different note—the sixth note of the major scale.

Example 7

The notes and key signatures of C major and A minor are identical. The only difference is that the minor scale starts on the sixth note of the major scale. Scales sharing the same notes and key signatures are called relatives. A minor is the relative minor of C major, and C major is the relative major of A minor. (Scales beginning on the same note, but sharing neither the same key signature nor all of the same notes, are called parallel; for example, C minor is the parallel minor of C major.)

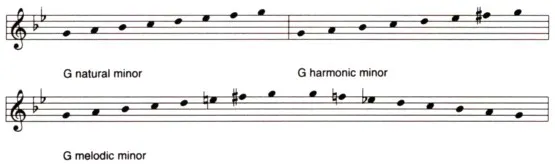

The two other common forms of the minor scale—both of which, like the natural minor, begin on the sixth note of the relative major scale—are the harmonic and melodic minor. The only difference between the natural and the harmonic minor scales is that the seventh note of the harmonic minor is raised half a step above the seventh note of the natural minor, creating a 1½-step (augmented 2nd) gap between the sixth and seventh notes in the scale. So, for example, the notes in the A harmonic minor scale are the same as the notes in the A natural minor except that the seventh note in the harmonic minor scale is a G♯ rather than a G♮ (G natural); and the distance from F (the sixth note in the scale) to G♯ is 1½ steps (an augmented 2nd).

The only difference between the natural minor and the melodic minor scales is that the sixth and seventh notes of the melodic minor are raised half a step above those of the natural minor when ascending; when descending, the notes of the melodic minor are the same as those of the natural minor. For example, the only difference between A natural minor and A melodic minor are that when ascending the sixth and seventh notes of the melodic minor are F♯ and G♯ rather than F and G natural as in the natural minor. (When descending, the two scales are identical.) The following example shows the differences between the G natural, harmonic, and melodic minor scales:

Example 8

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Copyright

- 1 Scales

- 2 Chords

- 3 Chord Progressions

- 4 Melody

- 5 Form

- 6 Useful Techniques

- 7 Instrumentation

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access An Understandable Guide to Music Theory by Chaz Bufe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Theory & Appreciation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.