- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Poor Relief and Community in Hadleigh, Suffolk 1547–1600

About this book

At the cutting edge of new social and demographic history, this book provides a detailed picture of the most comprehensive system of poor relief operated by any Elizabethan town. Well before the Poor Laws of 1598 and 1601, Hadleigh, Suffolk—a thriving woolen cloth center with a population of roughly 3,000—offered a complex array of assistance to many of its residents who could not provide for themselves: orphaned children, married couples with more offspring than they could support or supervise, widows, people with physical or mental disabilities, some of the unemployed, and the elderly. Hadleigh's leaders also attempted to curb idleness and vagrancy and to prevent poor people who might later need relief from settling in the town. Based upon uniquely full records, this study traces 600 people who received help and explores the social, religious, and economic considerations that made more prosperous people willing to run and pay for this system. Relevant to contemporary debates over assistance to the poor, the book provides a compelling picture of a network of care and control that resulted in the integration of public and private forms of aid.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Poor Relief and Community in Hadleigh, Suffolk 1547–1600 by Marjorie Keniston McIntosh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The context of poor relief in Hadleigh

To make sense of Hadleigh’s system for dealing with the poor, we need to understand the setting within which it developed and functioned. This little town had an unusually interesting history during the mid and later sixteenth century. As well as being a successful cloth-manufacturing centre, it gained an early exposure to Protestant beliefs during the latter part of Henry VIII’s reign and under Edward VI; its reformist rector and his curate were then burned at the stake under Mary. The town was run by a self-appointed group of 20–25 men who termed themselves the Chief Inhabitants, though they held no formal authority at all.

Hadleigh’s physical setting and neighbourhoods

The parish or, as it was occasionally called, the ‘township’ of Hadleigh lay near the Stour valley of south-west Suffolk, some nine miles west of Ipswich and eight miles south-south-east of Bury St Edmunds.1 Its 4,288 acres included the urban community in the centre, along the river Brett, plus agricultural land and a few scattered sub-settlements. The rural areas were devoted to mixed farming, with small enclosed fields used for raising grain and other arable crops intermingled with pasturage for animals, especially cows and pigs.2 As was common in this region of Suffolk, Hadleigh did not have a single, dominant manorial landlord but was instead divided between multiple estates: three larger manors and two lesser ones, most of which held land in other parishes as well. Beginning in AD 991, the main manor of Hadleigh was held by Canterbury Cathedral Priory and after the Reformation by the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury; Toppesfield manor was held by a series of private owners.3 The primary residences of those two estates were located on either side of the parish church in the centre of the town, and they divided urban properties and the river’s corn (or grain) mills between them. The manor of Lafham, later known as Pond Hall, lay on the eastern side of Hadleigh and was acquired by the D’Oyley (Doyle) family in the fifteenth century.4 The smaller manor of Cosford Hall, located to the north of Hadleigh, went with Pond Hall into the D’Oyley’s hands, while the little manor of Mausers or Hadleighs was bought by the Timperleys of Hintlesham in the fifteenth century. Because lordship was so fragmented, manorial authority had relatively little impact and will receive scant mention in this study.

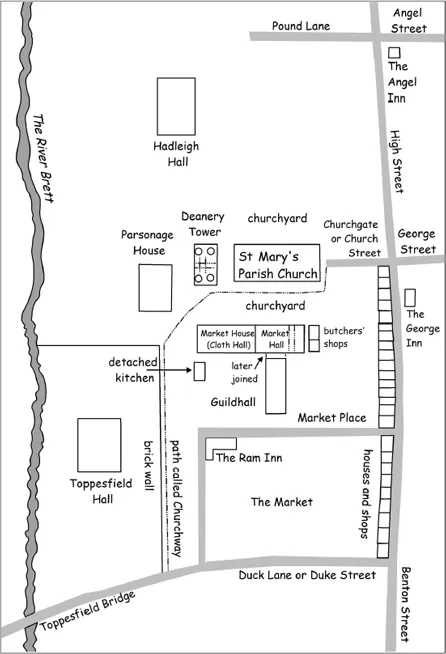

Figure 1.1 Major buildings in central Hadleigh, sixteenth century.

Hadleigh’s urban core had evidently been laid out in the earlier medieval period as a regular gridwork of streets, though it did not develop fully.5 Two primary bridges crossed the river on the edges of the town: Hadleigh Bridge to the north, and Toppesfield Bridge to the south. By the Elizabethan period the town’s physical, religious, economic and social centre was situated in a cluster of buildings that lay to the west of what is now High Street, Hadleigh’s main north-south thoroughfare, between Hadleigh Hall and Toppesfield Hall. As Figure 1.1 shows, that area contained the parish church (dedicated to St Mary) and cemetery, the parsonage house, the Deanery Tower and the marketplace with its associated buildings (the Market House, Market Hall and Guildhall).6

The religious buildings were the most impressive. Hadleigh’s church had been enlarged in the Decorated architectural style during the fourteenth century, with only its tower remaining from the previous structure; at the peak of the town’s prosperity in the fifteenth century parts of the church were rebuilt in the Perpendicular style, adding a clerestory and large stained glass windows.7 The church’s tower contained six medieval bells, and the clock on its eastern face had a fourteenth-century bell that rang the time. Thanks to the generosity of pious merchants and clerics, St Mary’s was well provided with crosses, plate, vestments and some books prior to the Reformation.8 Behind the church stood an imposing three-storey tower erected by William Pykenham in the 1480s or 1490s.9 Pykenham, rector of Hadleigh and Archdeacon of Suffolk by 1471, apparently intended this grand building, made of brick with four crenellated corner towers, as a gatehouse that would lead from the church to a rectory dwelling nearer the river, which he probably intended to rebuild as well. His death in 1497 prevented the latter, leaving an old timber-frame structure as the parsonage house.

Hadleigh’s marketplace and the buildings near to it have an atypical history because from the early fifteenth century they were held by feoffees (or trustees) on behalf of the town.10 In 1252 the manor of Toppesfield was granted the right to hold a weekly market, and in 1417/18 the lords of Toppesfield granted to feoffees a piece of ground near the churchyard and an adjoining unit called ‘Cherchecroft’. After Henry VI issued a confirmatory charter in 1432 for a weekly market to be held on Mondays and a three-day Michaelmas fair in late September, the property with market rights was conveyed to a new group of Hadleigh feoffees in 1438.11 The section of Cherchecroft next to the cemetery now included ‘one long house newly constructed called le markethows, with the chambers existing below the same called almessehouses’. The market and fair were held on the open space that extended eastward from Toppesfield Hall to what is now High Street and northward from what is now Duke Street to the churchyard. Around 1451 the market feoffees erected a three-storey building with two shops below it immediately next to the older Market House. By 1469, the building formerly termed the Market House was being called the Cloth Hall, suggesting that its large upper room was used primarily for the inspection and sale of textiles, while the recently built unit had not yet acquired its later name of the Market Hall. A grant to new feoffees in 1496 indicates that the Cherchecroft property was now called the Market Ground and contained three buildings: the Market House or Cloth Hall with the rooms beneath it; the Market Hall, including two butcher’s shops, priests’ chambers and a wool house; and a newly built Guildhall somewhat to the south.12 The Guildhall was at first connected to the Market Hall by an external passageway but later was extended so that all three buildings joined.

Before the Reformation, the Guildhall was the meeting place of Hadleigh’s five lay religious fraternities, to which many male household heads belonged, perhaps joined by their wives. In addition to supporting lights to their patron saints in St Mary’s church, each guild hosted an annual feast and probably provided assistance to its members in times of need, using the funds required for admission and income from the land they had been given. Although we lack a listing of guild participants, we know that between 1542 and 1545 they were headed by some of the town’s leading men; when guild money was loaned (with interest charged) to probable members, they were people of middling status within the local economy: two weavers, two cardmakers, a carpenter, a butcher, a plumber and a cobbler, as well as a clothmaker and a yeoman.13

In 1547, all guilds in England were terminated by the central government and their property declared subject to confiscation by the crown.14 Although Hadleigh’s guilds managed to sell their movable goods and probably their stocks of land, money and animals before they were seized, they lost the Guildhall. The Guildhall was later bought from the crown by several non-local gentlemen, who sold it in turn to Henry and Richard Wentworth. Hadleigh’s Chief Inhabitants then decided to acquire it for the town. In 1569 Robert Rolfe, an important clothier acting on behalf of the Chief Inhabitants, presented a tun of wine [252 gallons] to ‘my Lady Wentworth’; three years later the town was apparently engaged in legal action with the Wentworths, for the Chief Inhabitants allowed £5 to Rolfe and £21 5d to Thomas Alabaster as reimbursement for their expenses ‘about the town suit’ or ‘suits in law’.15 In December 1573 the dispute between the Chief Inhabitants and the Wentworths was resolved by arbitration: representatives of the town were to pay 100 marks to obtain ownership of the Guildhall. The town book notes for 24 December 1574: ‘We have bought of Mr. Henry Wentworth all his title in the town house otherwise called the gelde hall, for the which we have disbursed in ready money besides all other charges – £66 13s 4d.’16

During the rest of the Elizabethan period, the Guildhall and adjoining buildings were employed for a variety of purposes, including renting out certain rooms, using other areas for storage and – at least by 1589 – accommodating the town’s workhouse. The Guildhall and the open area beside it were also the setting for stage plays. Hadleigh’s players had already been performing by 1482; in the 1520s they travelled to Tendring Hall to entertain the Duke of Norfolk and in the 1530s to Canterbury.17 Despite the Reformation, they continued to put on plays at least locally until the end of the sixteenth century, paying 5s to the town for use of a large room in the Guildhall or the space outside it. In 1597, the Privy Council wrote to the sheriff of Suffolk, William Forth of Hadleigh, and two esquires, reporting that it had been told of a plan in the town ‘to make certaine stage playes at this time of the Whitson holydaies next ensuinge, and thether to draw a concourse of people out of the country thereaboutes, pretending heerein the benefit of the towne’.18 The Council prohibited the idea, especially at a time of food scarcity, ‘when disordred people of the comon sort wilbe apt to misdemeane themselves’. The recipients of the letter were to ensure that local officers did not go forward with the plan and that the stage prepared for the plays be ‘plucked downe’. From then on, players apparently moved inside and were regulated more closely. In 1599, John Allen, Hadleigh’s market bailiff and keeper of the workhouse located in one section of the Guildhall, was instructed not to permit any plays to be performed in that building without consent of six of the Chief Inhabitants; all plays or wedding festivities were to end before dark and to cause no damage to the building.19

The rest of central Hadleigh consisted of a mixture of residential housing, shops, inns and production units.20 In the Elizabethan period neighbourhoods varied considerably in terms of the wealth and occupations of their household heads, but each contained people of diverse statuses. The people living and working within them must therefore have had some vertical as well as horizontal interactions with their neighbours. Dealings across economic and social groupings may in turn have contributed to a sense that Hadleigh was a single community and had a shared identity.

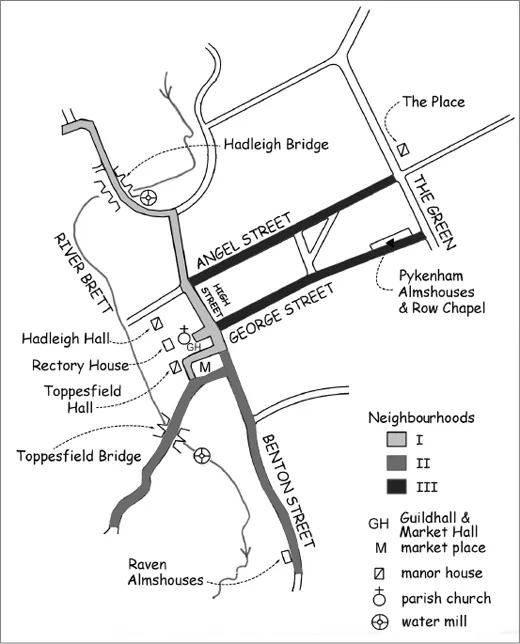

Figure 1.2 Three neighbourhoods used for collection of poor rates, 1579–85.

Hadleigh’s 660–780 households can be divided into four main economic groups, averaged over the years 1579–94, thanks to information about people who paid poor rates or received relief and other assorted sources.21 Category A consisted of the wealthiest 6 per cent, those whose heads paid poor rates on a weekly basis, for a total of 4s 4d to £1 6s annually. Category B included another 15 per cent whose heads paid only quarterly, for a total of 4d to 4s annually. The third and by far the largest category, coming to 66 per cent, comprised those households that neither paid rates nor received assistance. The remaining 13 per cent, Category D, contained members who were relieved by town officials. Though we have no locational information for most people in categories C and D, several of the poor rate records list payers in Category B by street, and we know the residences of many people in Category A.

Figure 1.2 displays the three areas within which poor rates were collected, giving modern street names.22 Neighbourhood I formed Hadleigh’s wealthiest area. Of 133 households in Categories A and B (though they were not all there at the same time), 23 per cent were in Category A and the rest in Category B. That neighbourhood contained many clothiers, mercers or gentlemen, and most of the people in Category B were independent craftsmen or traders.23 Angel Street and George Street acquired their names from the respectable inns that lay at the corners where they intersected High Street. Neigh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Appendices

- Acknowledgements and Conventions

- General Editor’s Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 The Context of Poor Relief in Hadleigh

- 2 Hadleigh’s System of Assistance

- 3 Recipients of Relief and Their Households

- 4 The Care and Training of Poor Children

- 5 Aid to Ill, Disabled and Elderly People

- 6 Why?

- Appendices

- References

- Index