- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

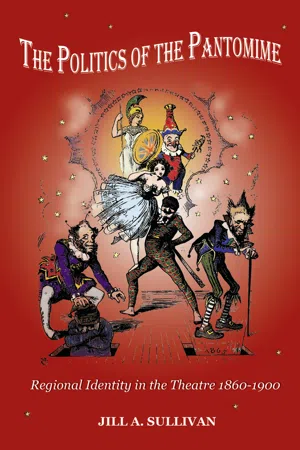

Dynamic and unique, this history examines pantomime productions in the English provinces—especially Birmingham, Nottingham, and Manchester—from 1860 through 1900. Arguing that pantomimes were rooted in specific expressions of local identity, this volume explores censorship as well as the relationships between theaters, their managers, authors, and audiences. A valuable contribution to the study of Victorian popular culture, this account also demonstrates how regional pantomime theater utilized political satire to its full advantage due to its geographical and creative distance from London.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Politics of the Pantomime by Jill Sullivan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Spectacle of Pantomime

1

The gorgeous Christmas pantomime

In late November 1860, theatre managements around the country began their preparations for the Christmas pantomime. Depending on the resources of the individual theatre, the pantomime might be a bought-in production from one of the London or other provincial theatres, a production wholly created in the local theatre, or one that drew on both locally produced and bought-in elements of scenery and script. The decision rested on the financial capabilities of the theatre, the pecuniary skills of the management and the success or failure of the preceding autumn drama season. An astute investment of time and money was crucial as the profit from the pantomime would contribute significantly to the realisation of a successful theatre season for the remainder of the year (as well as potentially providing funds for necessary alterations or repairs to the building). The Manchester Weekly Times in its preview of the forthcoming production in 1860 proclaimed that:

What would become of us if it were not for our pantomimes? so say all of us, managers the most earnestly, for pantomime has become - ‘O tempora, O mores’ - the sheet anchor of the drama. If it were not for that raddled face and those spangled pantaloons, what would become of Shakespeare and Sheridan. The former bring grist to the mill, the great immortals gobble it up.1

John Knowles, the proprietor of the Theatre Royal, Manchester echoed these sentiments at the 1866 Select Committee on Theatrical Licenses and Regulations, stating that ‘in most country towns, pantomime is ... the sheet anchor of the drama at the present moment’.2 It was crucial, then, that theatre managers provided not simply an annual pantomime, but one that both corresponded to specific expectations regarding the format and reflected national and local innovations. Traditions and variation, national patterns and local identity all shaped productions at the theatres in Manchester, Birmingham and Nottingham.

By the 1860s, the audiences of the Midlands and North West who visited their local theatres at Christmas were partaking in particular theatrical traditions and developments that epitomised pantomime productions by mid-century.3 Throughout the period the theatre managements in all three centres adhered to the basic format of pantomime, which comprised the ‘opening’, culminating in a transformation scene, followed by a short harlequinade, and concluding with an optional finale, sometimes a ballet or tableau such as ‘Shadow and Sunshine’ at the end of Harlequin Sinbad the Sailor; Or, the Red Dwarfs, The Terrible Ogre, and The Old Man of the Sea (Theatre Royal, Birmingham, 1865) or ‘Flora’s Home Amid the Honey Bouquets in the Garden of the Fairy Queen’, which concluded Robinson Crusoe at the same theatre two years later, in 1867.

During the 1860s and 1870s, the pantomime would often be preceded by a short opening play, usually a comedy or farce, a practice which lasted until the discontinuation of the stock company at the local theatres. At Manchester and Nottingham this change occurred in the late 1870s, but the Theatre Royal, Birmingham was - according to its manager Mercer Simpson - the last provincial theatre to engage a stock company: not until the 1880-1 theatre season did he have an entire season that comprised touring theatre companies.4 By 1880 the pantomime at all theatres took up the entire bill and three to three and a half hours appears to have been the accepted length of a performance. In 1890, the Birmingham Daily Gazette commented that a rehearsal of The Forty Thieves had been ‘compressed into a little over four hours’. The reviewer suggested that ‘with a judicious cut here and there, we fully expect to see it squeezed into the usual three and a half hours’.5 However, there were exceptions: the 1862 production of The House That Jack Built at the Manchester Theatre Royal lasted an exceptionally short two hours, whereas The Queen of Hearts at that theatre in 1884 exhausted its first-night audience with a five hour performance. Such excesses were not unknown at Drury Lane, but at the provincial theatres pantomimes of this length would have been edited after the first night.

Traditionally, the pantomimes opened on Boxing Day and, as Jim Davis has recently highlighted, this night combined the fashionable and the popular, with theatres up and down the country packed with expectant audiences.6 This particular tradition was not comprehensively adhered to: the multiple and highly competitive theatre managements in Manchester regularly opened their pantomimes prior to Boxing Day, sometimes by as much as a week or ten days. Most theatres shut for a rehearsal week prior to the first night, but such measures rarely guaranteed a flawless performance. Scenery would stick, the dancers were not necessarily performing in unison and lines were forgotten. Both press and audiences alike were sympathetic; the difficulties of the first night - often compounded by the piece overrunning until past midnight - were also regarded as yet another tradition. What would have been unforgivable in opera or drama was permitted at the pantomime. Very occasionally a public dress rehearsal would be held, such as that at the Theatre Royal, Nottingham in 1866, but all theatres would have staged a formal rehearsal for the press and invited guests a few days prior to the opening night. Subsequent previews, prompted by the theatre management, emphasised features that were also central to the initial newspaper advertisements. The promoted features highlighted the often extravagant expenditure on productions: between 1860 and 1900 this emphasis slowly shifted from scenic spectacle to the names of the specially engaged company, including stars of the burlesque and music-hall stage, variety acts and, by 1900, the biograph.

As the following chapters will illustrate, theatre managements all faced the annual dilemma of providing their audiences with particular elements of nationally recognised traditions, such as the transformation scene and the harlequinade, as well as responding to the latest innovations in spectacle and effects, whilst aiming to sustain audience figures for the two- or three-month run and conclude the Christmas season with a profit. In order to maintain audiences and income, many theatres resorted to what was termed the ‘Second Edition’ and, very occasionally, a ‘Third Edition’ in late January or early February. This later edition of the pantomime could include new songs, comic ‘business’ and new costumes; sometimes one or two new sets would be provided, or some of the pantomime roles recast. On rare occasions, if both the press and public had remained unforgiving after the first night, the pantomime might be completely rewritten. At some theatres, for example the Prince’s Theatre in Manchester, the Second Edition itself became a tradition. The revised version was reviewed in the local press as another stage in the organic development of a good pantomime, one that was to be expected of that theatre. In marked contrast, the management at the Theatre Royal in Birmingham refused to openly acknowledge that the pantomime needed revising, and although new features may have been added after Christmas, it was never advertised as a Second Edition. The local press again supported this decision; when in February 1894 the pantomime was revised to include new songs and jokes, the Birmingham Daily Post merely commented that such small changes were always necessary in a pantomime.7

By mid-century the productions were dominated by the opening, which consisted of between ten and twelve scenes. It was invariably based on a well-known story or fairy tale and recurring popular titles in this period included Dick Whittington, Robinson Crusoe, Aladdin, Blue Beard, Babes in the Wood and The Forty Thieves. By the 1860s, the first two scenes of the pantomime often followed a specific pattern: Scene 1 would be a ‘dark’ scene featuring nefarious magicians, evil spirits and ogres plotting to thwart the hero within settings such as ‘The Magician’s Study in the Temple of the Thundering Winds’, which opened the Nottingham pantomime of Aladdin in 1866, or ‘The Storm King’s Lair under the Deep Blue Sea’, which began Robinson Crusoe at the Theatre Royal, Birmingham in 1878. The dark scene would be followed by a second, contrasting scene wherein the Fairy Queen counterplotted to aid the hero. Such oppositions established the moral outcome of the story, with the attributes of the demons and fairies being sustained by the characters in the main plot: the hard-working and virtuous hero and heroine, and the profligate baron or wicked uncle.8 This scene order had been established in the pantomimes of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and was regarded by the newspaper reviewers as traditional, but, as Michael Booth has noted, the sequence could be reversed in pantomimes produced after the mid-nineteenth century.9 Certainly, evidence from the provincial theatres illustrates variations in the scene ordering of pantomimes of the 1860s and 1870s. For example, in 1867 at the Theatre Royal, Birmingham, the opening scene to establish the pantomime story of Robinson Crusoe was interrupted by ‘Mischief’; the first, celebratory scene in The Fairy Fawn (1872) was similarly interrupted by the uninvited bad fairy ‘Argentina’, and the opening scene of the Comedy Theatre production of Dick Whittington in Manchester in 1887 included both the good and wicked fairies debating the future of the hero. Equally, the ill-will of demons could be enacted by mortal villains in the opening scene, such as Idle Jack in Dick Whittington of 1870, or the family solicitor in Puss in Boots of 1875, both staged at the Theatre Royal, Birmingham. The 1869 and 1876 productions at Nottingham opened with the fairy scene, and in Blue Beard (1877) the ‘Abode of the Goblin King’ was moved to Scene 2 whilst the pantomime opened in Toyland, populated by a selection of topically well-informed and disgruntled dolls. In The Pantomimes and All About Them (1881), Leopold Wagner stated that many librettists had stopped including an opening demon scene, but evidence from Manchester and Birmingham shows that the traditional opening dark scene, whether solely the domain of demons or interrupted by good fairies, was in fact sustained into the 1890s.10

The remaining eight or ten scenes of the pantomime opening pursued the story of the title, the pantomimes of the mid-century culminating in another ‘dark’ scene where the hero and heroine were trapped (recalling the Georgian and early Victorian harlequinades in which Harlequin customarily lost his magic bat and had to be rescued).11 Once again the fairy appeared, to release the heroes and punish the wrongdoers, and the transformation scene followed marking the end of the opening. Whereas in pantomimes at the beginning of the century the short, spoken opening was a prelude to the longer, mimed activity of the harlequinade, by the 1860s the opening contained full, scripted dialogue. Portions of the libretto were printed and available to the audience as a ‘book of words’, which were on sale in the theatre for 1d at Nottingham and 2d at the Birmingham and Manchester theatres.12

The opening did not simply tell the tale; it was an opportunity for scenic display, grand ballets, music and comedy. Much of the last involved burlesque, so much so that the opening was often referred to as the ‘burlesque opening’.13 A popular genre that had emerged in the 1850s and 1860s, burlesque ‘was a compound of music hall, minstrel show, extravaganza, legs and limelight, puns, topical songs, and gaudy irreverence’.14 In particular, burlesque was predicated on parody and satire, and pantomime plots increasingly included liberal imitations of well-known plays and operas. The pantomimes at Nottingham, for example, could include parodies of Shakespearean drama, such as that of Macbeth in 1876 (‘Is this a corkscrew I see before me’) or of Othello in Little Red Riding Hood (1873):

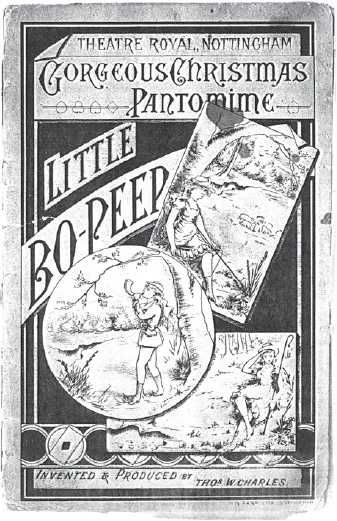

Cover of the 1883 book of words from the Theatre Royal, Nottingham, Little Bo Peep.

BARON. ‘One more, one more - when I have plucked thy rose’

GRANNY. Oh! Where’s my handkercher? let’s blow my nose.15

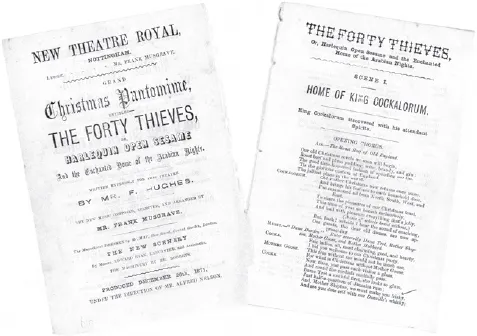

Book of words from the Theatre Royal...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part One The Spectacle of Pantomime

- Part Two The Social Referencing of Pantomime

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index