- 148 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

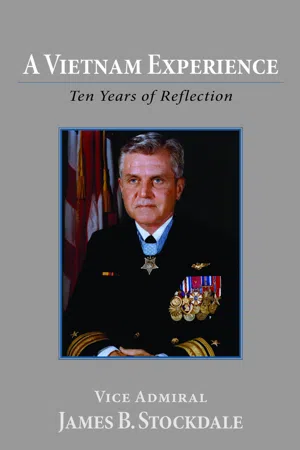

The decade that followed James Stockdale's seven and a half years in a North Vietnamese prison saw his life take a number of different turns, from a stay in a navy hospital in San Diego to president of a civilian college to his appointment as a senior research fellow at the Hoover Institution. In this collection of essays he offers his thoughts on his imprisonment. Describing the horrors of his treatment as a prisoner of war, Stockdale tells how he discovered firsthand the capabilities and limitations of the human spirit in such a situation. As the senior officer in confinement he had what he humbly describes as "the easiest leadership job in the world: to maintain the organization, resistance, and spirit of ten of the finest men I have ever known." His reflections on his wartime prison experience and the reasons for his survival form the basis of the writings reprinted here. In subject matter ranging from methods of communication in prison to military ethics to the principles of leadership, the thirty-four selections contained in this volume are a unique record of what Stockdale calls a "melting experience"—a pressure-packed existence that forces one to grow. Retired Vice Admiral James B. Stockdale, a Hoover Institution fellow from 1981 to 1996, was Ross Perot's 1992 presidential running mate and a recipient of the Medal of Honor after enduring seven and a half years as a prisoner of war in North Vietnam. He died in 2005 at the age of 81.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Vietnam Experience by James B. Stockdale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE WAR COLLEGE YEARS

II. After two and a half years in the aviation command job and a year in the Pentagon, I got the third star of a Vice Admiral and was ordered to become the President of the Naval War College at Newport, Rhode Island. That was where I belonged. High command of a peacetime military force was not for me. My natural inclinations and the practicalities of fate had shaped my drives toward those of a teacher.

Although since I had been repatriated I had gone through the motions of presiding over peacetime operations and jumping through the right hoops in the Pentagon, in a true sense all that had been a big comedown from my professional experiences in Vietnam—first a squadron commander and then a wing commander airborne with my pilots in the flak, and finally for years boss of the prison underground in Hanoi. In those jobs under life and death pressure, what I said, what I did, what I thought, really had an effect on the state of affairs of my world. It was a real world, not a paper world. I had to convince real people, people with a certain independent freedom of action, that my ideas were good; being an actor-functionary in a drama of functionaries, all players being on predictable tracks, was tame fare by comparison.

I was glad to be back in the world of ideas. I wanted to teach people about war. I had been a ringside witness to the disaster of a nation trying to engage in war while being led by business-oriented systems analysts who didn’t know anything about it.

The Naval War College of Newport, Rhode Island, was the first senior service college to be founded in America. Now over a hundred years old, its purpose is to give senior officers (colonels, Navy captains) a sabbatical from routine peacetime duties to study history, international politics, and associated subjects, to focus on war as a unique and crucial component of the human predicament. Its founders, Stephen Luce and Alfred Thayer Mahan, had the foresight to realize that peacetime military organizations need a permanent intellectual fountain of strategic insight and enrichment lest they become dominated by bureaucrats. By tradition, the Naval War College has civilian faculty members: historians, political scientists, and economists with teaching experience in the best universities in New England. As their team-teachers are selected bright and experienced military officers. The “students,” professional military officers in their forties, take up residence in Newport, with their families, for a full school year.

The fall of 1977 found Syb and me in the lovely old colonial mansion that is the President’s House, overlooking Narragansett Bay, Stan with us there as a day student in a local prep school, Taylor at Rumsey Hall school down in Connecticut, Sid in college in Colorado, and Jimmy, now married to Marina, teaching in a private school in Columbus, Georgia. My boss, Admiral Jim Holloway, Chief of Naval Operations, came up from Washington on a chilly October day to preside at the brief ceremony before student body and faculty as I took over. My remarks of that day appear below.

WAR AND THE STUDY OF HISTORY

Change of Command Address, Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island, October 1977

It has been said that “… everything depends upon the person who stands in the front of the classroom. The teacher is not an automatic fountain from which intellectual beverages may be obtained. He is a witness to guide a pupil into the promised land; but he must have been there himself.” This faculty has been there, and they hold the respect that goes with that qualification.

I spent this week with the Academic Department Heads. And, at the urging of Professor Phil Crowl, by way of preparation, I consulted The Oracle. If you remember Phil’s article in the Naval War College Review, you will recall that his is not The Oracle of Delphi but The Oracle of Newport, Rhode Island, a man I can now call my predecessor, Alfred Thayer Mahan. I’ve studied lectures Mahan gave here nearly one hundred years ago—one given in the year 1888 right over here at Founders Hall in the third year of his first term as President; another given four years later in 1892, just after he came back for his second term as President, delivered here to my right in what was then the brand new Luce Hall. Besides their courtliness (they are always addressed to the “Gentlemen of the Navy,” which I thought rather classy), one of the first things to strike you is the timelessness of these talks. Their content verifies the wisdom of the philosophy he institutionalized here. In my words, “that in the profession of arms, historic evidence indicates that the method of their employment is at least as important to victory as their design, and that the capstone of a mature officer’s education should focus on style rather than hardware.” In Mahan’s words, “the great warrior must study history.”

Mahan is not blindly dogmatic and he is openly distrustful of simplistic historic analogies. But he nevertheless believes that an educated man with sufficient classical background can often perceive recognizable trends in events that occasionally allow him “that quickness to seize the decisive features of a situation and to apply at once the proper remedy—a stroke which the French call coup d’oeil, a phrase for which I know no English equivalent.” He explains that what he speaks of is a memory bank full of historic facts that, after a fashion, form distinctive and educational patterns. Example: in the late 18th Century, French armorers discovered a method of casting cannon barrels that not only improved their accuracy but made them much lighter. To the pedestrian officer the latter advantage was a convenience. But to the Corsican Corporal of Artillery with a sense of history, and more than a little genius, the change portended an entirely new and different utilization of the weapon. It was not to be towed slowly across the plains by oxen, but quickly across the Alps by horses. Forts were to be bypassed, firepower concentrated. What was to the man on the street a metallurgical convenience was to Napoleon a geopolitical event that led to the conquest of Europe. History is full of similar examples. In our age, what was to us a nuclear event was to Hyman Rickover quite a different thing.

Another of the timeless aspects of Mahan’s lectures was the clear evidence of the pressures and crosscurrents concerning War College course content that he experienced even when this school was in its infancy, the world’s first War College. Throughout his talks he’s obsessed with the definitions of practicality and theoretical considerations. And he talks somewhat humorously of his contacts with friends in Washington when they ask him, as he steps out of the Army-Navy Club on a brisk evening, “Are you going back to the War College? Do you expect to have a session there?” “Yes,” he answers. One of his senior friends then sneers, “Are you going to do anything practical this time?” Offended, Mahan replies with questions like “What do you mean by practicality?” and so on and so forth. This theme is woven throughout his lectures. The preoccupation is there, and it is clear that he was under pressure. This pressure can still be felt.

Now, subject to possible direction by my boss, Admiral Holloway, I would like to state that I plan to make no abrupt changes in the curriculum. I get a lot of mail on this subject, from everybody from old retired acquaintances to boyhood friends. One letter that I got from a boyhood friend a few days ago read in part as follows, “… on the subject of the College curriculum, you mentioned that you have been bombarded with conflicting advice. That cross will be yours to bear as long as you are there. My advice is that you ignore all of us and get on about your own business.” That letter dated the 3rd of October 1977 and signed by Stansfield Turner.

So I do this afternoon get on about this business of educating our most promising mid-career officers. And I do so with a sense of mission and, in all honesty, with a very comfortable degree of self-confidence. For although it will take me a few months to get up to speed on all the disciplines taught here—and I think they are the right disciplines—each in my view has blind spots in critical areas vis-à-vis the nature of war itself. On the national scale, failure to account for this has cost us dearly in the recent past.

If I can firmly establish and illuminate to the students here the inevitable blindnesses of these particularized specialties or disciplines in which we must work—blindness to the psychological and subjective, as well as the objective totality of the human experience we call war—I think I will have done something for my country.

We have at times made assumptions that did not account for such facts as: (1) War is a serious business; (2) People get mad in war; (3) The laws of logic are valueless in bargaining under those circumstances; and so on. We, they, everybody should be assumed to be ready to throw proffered options in the face of the enemy. After all, their and our honor is at stake. A force at war can’t feint and engage and disengage like an adagio dancer, and it’s well to know that before you go into combat.

As the German soldier and philosopher Clausewitz has said, “War is nothing but a duel on a national scale.” And I think a professional military man can learn some bad habits by leading a life that is totally devoted to orderly processes. Duels, or street fights, are not orderly processes. Yet they are very good analogies to war.

In short, I don’t think there is anything new under the sun, or that we’re seeing the dawn of any new age. I think we can be grossly misled by statements of some of the so-called defense intellectuals of the sort commonly appearing even now, in the post-Vietnam era. For example, I quote from a scholar in a recent issue of a highly respected journal. “Waging war is no different from any resource transformation process and should be just as eligible for the improvements in proficiency that have accrued elsewhere from technological substitution.” My experience, and it has been rather recent, puts me back in old Clausewitz’ camp. He said, “War is a special profession. However general its relation may be and even if all the male population of a country capable of bearing arms were able to practice it, war would still continue to be different and separate from any other activity which occupies the life of man.” Another old warrior, William Tecumseh Sherman said, “War is cruelty and you can’t refine it.”

I think, faculty and students, that we are involved in an enterprise that deserves our best attention. And I am glad to address it with you.

At the Naval War College I had my own press that put out, among many other things, a periodical to a wide professional officer and national security academic audience: The Naval War College Review. I always wrote a short lead article for that under the title “Taking Stock.” I also found myself being invited to make dozens of speeches—commencement speeches at civilian colleges, sermons at local churches, talks to professional societies. Then there were magazine articles. And all this was in addition to institutional affairs and classroom teaching, which I soon took up.

Below, in chronological order—at least in terms of time of composition—are an assortment of all of the above. Within a week of the time I took over the President’s job it was time to compose the piece below for the Winter NWC Review.

TAKING STOCK

Naval War College Review, Winter 1978

I was both surprised and pleased during my first week as President of the Naval War College, to have had so many of those well-wishers who stopped in or phoned include in their remarks comments on the Naval War College Review. Many friends—active and retired officers, congressmen, educators, and others—closed our conversations with “keep the Review coming.” Not all its articles escape critical comment, but that is hardly surprising. This quarterly publication is not a house-organ, cranking out a particular party line, but a scholarly journal intended to stimulate and challenge its readers and to serve as a catalyst for new ideas.

I disagree with both the thrust and conclusions of some of the Review’s articles myself but my opinions do not necessarily detract from the value of those compositions. For instance, in this issue I take exception to Professor Hitchen’s writing on the Code of Conduct. The subject is, of course, very close to me and I have read countless articles about, and heard many proposals for, revising the Code. His is what I might call the outsider’s viewpoint; shared by many, it focuses on Article V (“… I am bound to give only name, rank, service number, and date of birth.”) as a flawed stipulation requiring revision. It has been my observation that those who have not served as prisoners of war but who write on such matters invariably assume that Article V is the “heart” of the Code. My further observation is that few of those who have been prisoners of war for a significant period of time have any trouble understanding or dealing with it. The Article is just a piece of good advice: to utter as little as possible except for the four items required under international law, at least until one is sufficiently certain of his ground to be able to use his words as weapons against his captors. That’s what Brig. Gen. S. L. A. Marshall meant when he wrote it, and that’s what it says.

If Article V was flawed, it was given clearer meaning in a Presidential Executive Order signed in November 1977. However, scarcely noted by commentators, a second, more important Executive Order was also signed at that time. That one dealt with Code provisions that have great significance for “insiders”; it dealt with command authority within a prison camp. The Code says that if one is senior he will take command and, that if not senior, he will obey the orders of the senior prisoner and back him up in every way. The shocking discovery for us who returned from North Vietnam was to be told that the Code did not have the force of law. Had this fact been generally known in prison, I’m afraid our POW military organizations would have been much less effective. Now that the cat is out of the bag, President Carter’s new Executive Order should go far toward remedying what could have been a serious problem in the next war. As for Professor Hitchen’s question: “Is the Code of Conduct required at all?,” I believe that the answer is “no” for about 60 percent of the American fighting men. However, some of us need its moral support to hitch up our courage, and a few of us need a little fear of the law to keep it hitched up.

Institutional nepotism aside, I thought Captain Platte’s multipolarity article was the finest in this issue. However, he isn’t immune from disagreement either. He believes the U.S.S.R. best suited by experience to play the balancer in a tripolar world. I would argue that China is equally experienced. The Chinese Communists’ World War II performance in fighting two enemies simultaneously, alternately siding with each against the other, must have set a record for aplomb and agility. At any rate, the true nature of their conflicts was certainly smoked by the man on the street in the United States. Americans, Captain Platte and I agree, will have the least affinity for three-cornered confrontations. Visualizing all the bad guys on one side and all the good guys on the other will never get us by.

I don’t intend these notes merely to be a rebuttal or even a comment on every article. Rather, I intend to use this space as a sounding board to float a few ideas of my own.

In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle, differing with his teacher Plato, held that although both are dear to us, piety requires that we honor truth even before our friends. I address this to my friends the strategists, the analysts, and the tacticians. The truth to be honored is that your analyses, your equations, your principles, and your plans too often are based on incomplete if not erroneous assumptions about the nature of man and the nature of war. The extension of rational management principles to planning and waging a war is obviously not without value. Indeed, to ignore those tools is crippling and criminally dangerous. Equally dangerous, however, is the belief that the uncritical application of those principles will bring victory in war. War is an irrational undertaking and there are no tenets of rationality to which all men subscribe. We may cry with Job, “Oh that mine adversary had written a book” but he hasn’t and yet we err in ascribing our own values, reactions, cultural processes, etc., to him. This “mirror imaging” is often warned against but as often forgotten. It is a blind spot or perhaps more properly, a false view, a mirage, that we must rid ourselves of. We must do it nationally and we are going to do it in our courses of instruction here at the War College. In a future issue of the Review I wish to look into some specific aspects of this subject.

In the first article of this issue, The Honorable Edward Hidalgo warns that striving to avoid error is not the same thing as seeking the attainment of a positive goal—that avoiding failure is not success. I intend that my term as President of the Naval War College be devoted to the quest for the positive goal, but that will require good judgment. It has been said that good judgment is based on experience, but that, unfortunately, good experience is based on bad judgment. Once upon a time I zigged when I should have zagged. At any rate—

The old order changeth, yielding place to new,

And God fulfills himself in many ways,

Lest one good custom should corrupt the world.

My second NWC Review article finally broached the subject that had been in my craw ever since my years spending my life locked in leg-irons on a cement slab bunk in central Hanoi listening to the carnival-like joyful noises in the streets o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword by Jeffrey C. Bliss

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- I. Unwinding in the Hospital

- II. The War College Years

- III. Breaking in as a Civilian Academic

- IV. Early Hoover Institution Years

- About the Author