![]()

1

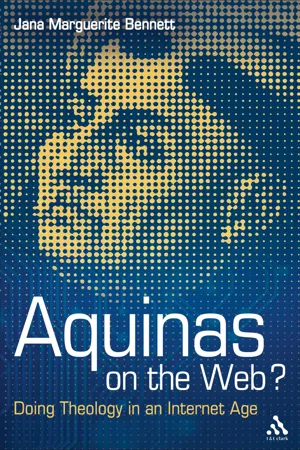

Can Thomas tweet? Theology about the internet

Kimberly Hope Belcher, Tweeting the Summa Theologiae?

Who would do that? [Oh, yes, I would.]

Obj 1:

Twitter is inappropriate for any serious endeavor. The ST is a serious endeavor. Therefore, it should not be tweeted.

Obj 2:

140 characters are not enough to get any real theology done.

Obj 3:

People on Twitter are unlikely to appreciate the substance and depth of Thomas Aquinas’ great work.

Contra:

“The Master of Catholic Truth ought not only to teach the proficient, but also to instruct beginners” (ST Prologue). Therefore http://twitter.com/summatheologiae.1

Thomas Aquinas does happen to be online in some fashion. In addition to the fact that his major work, the Summa Theologica, is being tweeted (an internet program that lets people transmit very short, instantaneous statements to those people who choose to “follow” them), he is on Facebook (an internet program that lets people “friend” others, whether they know them or not, and share mundane and also interesting information about their day, photos, and links to websites of interest), blogs (an internet version of a journal, though much more public), and web pages all his own. He has more than one Twitter account. He posts daily quotes, but what is rather more impressive is that he has a 140-character daily tweet his massive Summa Theologica.

The next question might well be whether it means anything of significance that Thomas is online and interacting with people via his twenty-first-century stand-ins. When I first started thinking about the way theology is done in an online context, it seemed to me that an apt analogy could be made between the means by which Thomas, in the thirteenth century, carried out his scholastic theology, and the means by which twenty-first-century people practiced theirs. Thomas’ disputational method took the form of first, asking a question, then probing the known authorities for their answers to the subject, developing an answer to the question that took those authorities into account (or, alternately, rejected those authorities for some good, stated reason), and then replying to the authorities on why his answer was better.

By comparison, many different kinds of internet conversations facilitate asking and answering theological questions that have some of the characteristics of scholastic disputation. For example, Yahoo! Answers is a website that invites people to ask questions such as: “Is studying Christian theology flawed because the entire subject rests on the belief that the myths are true?”2 Other internet users answer questions based on their knowledge and expertise. The question asker and other internet users then can read through the answers and make determinations about the best answers, and collectively, they can vote on the best answer. These questions often lead to further questions, again similar to the way disputational theology operated. The open-ended nature of the questions, the ability to consult a wide range of answers, and the evaluation of answers for their suitability are some of the points of comparison to Thomas’ work.

Like most analogies, of course, I found in time that this one fell short. There are ways in which internet theology is very unlike Thomas’ disputational method, such as the fact that on the internet, someone might claim to be authoritative about a subject on which they know nothing. The collective voices on the internet do not always do well in their assessment of answers; sometimes an answer is deemed “good” for its “coolness” factor. The amount of reflection that occurs over these answers is dubious by comparison to the thoughtful precision of Thomas’ analysis. Thomas’ authorities are far less able to be interactive with him than internet theologians tend to be with one another.

Still, theological conversation goes on and on; shouldn’t interested people be participating? Indeed, don’t Christians have something of a mandate to participate in theological conversations where they happen? The Christian tradition is, after all, comprised of people who care about what we say about God and how we say our words about God (I am thinking here about the many years of heated debate it took to develop the Nicene Creed that is familiar to so many).

Moreover, the theological conversations that happen on the internet have a tendency to spill over to “real life” and affect the theology done offline. Consider, for example, a chance remark that Pope Benedict XVI made on a plane trip in 2009. In an offhand comment made to reporters on his flight, the pope said that AIDS is “a tragedy that cannot be overcome by money alone, that cannot be overcome through the distribution of condoms, which even aggravates the problems.”3 What followed from his remark were days, and in some cases, weeks, of conversation about the pope’s comments, theologically and otherwise. The conversation did not chiefly take place among academic theologians, who had previously been seen as the purview for a debate like this, especially on such a hot topic as contraception. Yet, while a few academic theologians did weigh in on the pope’s comment, a search among the usual academic databases reveals very little commentary on condoms and AIDS. I suspect this is in part because academic theologians, particularly Catholic theologians, think that this is a tired debate (one that has been conducted since at least the promulgation of the 1968 document Humanae Vitae, which spells out the Catholic Church’s teachings on contraception) that has become rather irrelevant, since most American Catholics use artificial contraception anyway, and the magisterium has effectively prevented much conversation about it.

Rather, the lively conversation and vigorous debate on the Catholic Church’s teachings on contraception took place in the midst of a mostly nonacademic audience via Web 2.0 formats. This is not the first time a pope’s comment or remarks by other religious leaders has sparked debate in this form. Similar discussions emerge following mainline Protestant votes on homosexuality, for example, or in an evangelical Protestant conversation about Pastor Rob Bell’s book on universal salvation (I discuss this further in Chapter 5). In all of these situations, internet theology makes it onto the pages of the so-called secular media like the New York Times; the offline world marvels at the questions and intensity of the theological debate happening online.

Theology about the internet: The good, the bad, and the tool

That there is theology done online and that it has some kind of impact on offline theology is indisputable. Still, what is a Christian to do in terms of assessing these theologies? Just because theology is done online doesn’t make it right or good or fruitful for Christian life. For example, if we ultimately decided that the internet, as a medium, is evil, it would be rather pointless even to consider the question of whether to do theology there, any more than we could expect, say, reflections on whether murder is a theological act to lead us toward the mystery that is God.4

There have been several theologians who have raised good questions about the impact of the internet (and technology in general) on Christians’ ability to live as witnesses for God. This section discusses some of the key people who reflect about the internet. These are people largely reflecting on others’ activities, as outsiders, rather than approaching the theology from an insider’s vantage point.

Before I turn to reflection about the internet, however, some brief introduction to terminology and the state of the field is in order. One distinction is that between “online” and “offline” communication, or the online world in distinction with the “real world.” As Heidi Campbell suggests, “Online is applied to that which takes place in a computer network environment, such as interaction facilitated through the internet. . . . Similarly, the term ‘offline’ is used to describe any facet of life occurring away from the computer screen.”5 A second difference is the distinctiveness of Web 2.0 from its predecessor Web 1.0. Web 1.0 involved a person and a personal computer; as James van den Heever notes, “the application resides on the personal computer and so does whatever individual users use that application to create. . . However, as the Internet grew and developed its own culture, this paradigm began to change, and value began to move from the personal computer onto the Internet itself.”6 For example, one might consider the difference between websites that simply reiterate print information, and Web 2.0 websites that invite participation. To continue reflection on the Catholic Church, for example, we can consider that the Vatican’s website is primarily in Web 1.0 format, with not-very-easily-searchable content that mirrors the print copies of Lumen Gentium, Humanae Vitae, and the like. Their content was inputted on personal computers by Vatican officials; the appropriate Vatican office has say-so over the content; people can search the information and quote it, but they cannot change the content itself except by hacking the system. In Web 1.0, legal, social, and cultural boundaries are preserved.

By contrast, a definition from Wikipedia (of course) pinpoints what is meant by Web 2.0:

The term Web 2.0 is associated with web applications that facilitate participatory information sharing, interoperability, user-centered design,[1] and collaboration on the World Wide Web. A Web 2.0 site allows users to interact and collaborate with each other in a social media dialogue as creators (prosumers) of user-generated content in a virtual community, in contrast to websites where users (consumers) are limited to the passive viewing of content that was created for them. Examples of Web 2.0 include social networking sites, blogs, wikis, video-sharing sites, hosted services, web applications, mashups, and folksonomies.7

A common suggestion with Web 2.0 sites is that people have now entered a more democratic and freeing environment. In the imagination schooled by Web 2.0, Humanae vitae or any other Vatican document is open to user changes so that there is a communal sense of ownership with what is being written and posted. No one exclaims about copyrights, nor is anyone going to worry about whether John Doe can say what he just said in the text, because Web 2.0 simply does allow for and, more to the point, invites, that kind of interaction.8

One of the differences is that the internet has made its users “theologians” of a sort – even those who would not profess Christian beliefs find themselves using theological terms to describe the internet. For example, one technology blogger describes the “rapture” as the moment when there will be super intelligent machines.9 The internet has also caused Christians to think about theology and write about it, even if they are not clergy or professional theologians. As one blogger succinctly describes the Christian blogging world: “We know more than our pastors.”10

The internet as tool. . .

One prominent way of thinking about the internet is as a communication tool, like the telegraph or radio.11 On this paradigm, the perception is that the user bears the responsibility of determining how that paper or copy machine can be used (for throwing spitballs? Or for building origami?) because the tool itself is neutral. Those who subscribe to such a view often see that the internet is merely a recapitulation of what happened to theology during the advancement of the printing press. Elizabeth Eisenstein notes of the printing press: “[b]oundaries between priesthood and laity, altar and hearthside, were effectively blurred by placing Bibles and prayerbooks in the hands of every God-fearing householder.”12 So too, in an internet age, technology is blurring boundaries, but in a way that perhaps facilitates transmission of the gospel.

The internet is a medium for communication just like typewritten church bulletins were a medium for communication. Churches put their information “up” on the web because people use search engines to find that information, and some people exclusively so. The diversity of communication styles led, many hoped, to reaching diverse audiences and so drives the hopes of Christian evangelism in the twenty-first century.

The tool view is questioned by people who see that the internet is far more than a simple means of posting information that could otherwise be found in books. This is especially the case in a Web 2.0 world. Sherry Turkle, a psychologist at MIT who has studied the impact of computers, robots, and the internet on humans, writes against the tool view: “My colleagues often objected, insisting that computers were ‘just tools.’ But I was certain that the ‘just’ in that sentence was deceiving. We are shaped by our tools.”13 Naming the internet as a tool makes it seem to be something we can pick up and put down at will, as we would a hammer for constructing something, or a pen for signing a check. We do always have access to these tools in some kind of “Inspector Gadget” kind of way. Web 2.0, however, has perhaps given rise to tools that are often not separate. We can now name a technological class, people who are constantly connected to the internet via their smartphones, and who, moreover, find it exceedingly difficult to disconnect from them, as though their phones were a body part.

The internet as evil?

Some versions of “the internet as tool” recognize that tools are not merely neutral but, in fact, shape us and our ability to respond to the world well. So, some raise the question, “Is the internet a force for good or evil?” Is the internet largely good, or bad, for theology?

The quote at the beginning of this chapter about Thomas tweeting notes some of the reasons why theologians have been concerned about theology done on the internet: for example, that Twitter cannot be substantive or serious enough for thinking about the great Thomas Aquinas’ metaphysics and theology. Belcher imagines her interlocutors in this conversation, but the concerns she raises are concerns that underlie many peoples’ theological assumptions. In academia, online journals are often seen as lower in quality than offlin...