![]()

1

Silent American Films in Soviet Russia in the 1920s

The 1920s were a difficult decade for Soviet Russia. The Revolution of 1917 was followed by several years of Civil War. Hunger ravaged vast areas of the country. The economy was in disarray, with several years of War Communism being replaced by the more liberal New Economic Policy (NEP), which lasted from 1921 until 1928. This was followed by the radically different economic approach of the first Five-Year Plan and the beginnings of a planned economy. Russian society was going through changes on an unprecedented scale, with whole classes of people being virtually exterminated.1

Throughout this tumultuous decade with its many changes, one popular trend remained the same: the Russians, especially those living in urban areas, actively went ‘to the movies’, particularly the ones imported from America.2 This ardent movie going during times of such hardship in Soviet Russia can be compared to the tremendous popularity of cinema in America during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Before and After 1917: American Adventure Serials and the ‘Daredevil’ Pearl White

Russian fascination with American cinema pre-dated the Revolution. American films were first imported into Russia in 1915, and by 1916 they became Russia’s main foreign import.3 From that time, American adventure serials enjoyed vast popularity among Russian audiences. Most of these serialized films were structured around an active female lead character, played by the ‘serial queens’ Pearl White, Cleo Madison, Kathlyn Williams, Ruth Roland, and Helen Holmes.4 These fast-paced films abounded in chases and fight scenes and showed the latest American technology such as aeroplanes and automobiles. Of all the ‘serial queens’, Pearl White gripped the imagination of Russian viewers the most. Among the Pearl White films shown in Russia prior to and soon after 1917 were The Perils of Pauline [USA 1914], distributed in Russia under the name ‘Pod gipnozom millionov [Under the Spell of Millions]’; Exploits of Elaine [USA 1915], distributed as ‘Tainy Niu-Iorka [The Mysteries of New York]’; The Iron Claw [USA 1916], distributed as ‘Maska, kotoraia smeetsia [The Mask That Laughs]’; House of Hate [USA 1918], distributed as ‘Dom nenavisti [House of Hate]’; and Fatal Ring [USA 1917], distributed as ‘Sviashchennyi brilliant [The Sacred Diamond]’.5

The Russian press in the years preceding the Revolution documented the great popularity of American adventure and detective films. In 1917, M. Moravskaia wrote in Zhurnal zhurnalov (The Magazine of Magazines),

[Cinema’s] calling is to take one away from everyday life, to let one forget it. And also to imitate life, to create an illusion of great activity, a mirage of a different, foreign [ne nashei], full life, which anyone can experience for a small price, without moving from their seat.6

Two years earlier, a journalist in Petrogradsky kurier (The Petrograd Courier) noted that the audiences enjoyed watching the chases, ‘sensational murders’, and ‘mind-boggling stunts’ of imported films.7 The combination of the modern, daring physicality of actors and actresses who performed the stunts, the fast pace of chase scenes that often involved the latest technology, and the possibility of experiencing a different kind of life was what attracted wide numbers of male and female viewers to imported American films. While some journalists attributed these preferences to an ‘unhealthy psychology of the masses’, others pointed out the healthy roots of these films’ popularity. For example, Vladimir Zhabotinsky wrote in 1915,

Cinema is alive mainly due to the drama of its ‘sensational’ contents. Its strength and attraction are the jumps from a plane into a car, the shooting of bandits on the roof of a courier train, and so on. [. . . ] This popularity is, in essence, very healthy. It simply shows that the degree of individuality has risen in Europe. The human soul has become tired of the fish-like life that we lead in our police states; it wants, at least in pictures or on paper, to entertain itself with the smell of the physical struggle of strained muscles and blood.8

This telling analysis stressed not only the attraction to the speed and dynamism of modern American cinema, but also the nascent Russian (as well as European) desire to see more individualized heroes in films, as well as the need for physical engagement and struggle. The contrast that Zhabotinsky, an intellectual and one of the main authors of the newspaper,9 perceives between the inactive, ‘fish-like’ existence in pre-revolutionary Russia and the dynamic individualism of American films not only demonstrates the reasons for the popularity of American cinema in Russia, but also points to some of the social and psychological reasons for the attraction to the revolutionary ethos among the young Russian intellectuals. There is a definite parallel between the sense of modernity and struggle embodied in American adventure detective films and the leftist discourse of the Russian Revolution. As Lev Kuleshov insightfully explained in his book The Practice of Film Direction, written in 1935, ‘in our time [in the late 1910s and early 1920s] we were convinced that American montage invariably inculcated boldness and energy, indispensable to Revolutionary struggle, to revolution.’10

Pearl White was one of the earliest of Hollywood celebrities, at the very beginning of the evolution of the star system.11 In America, adventure serials were most popular with female audiences, who saw in their female stars the embodiment of the new, modern woman. Pearl White’s heroines in films such as The Perils of Pauline, Exploits of Elaine, Hazards of Helen, and House of Hate undertook thrilling adventures and possessed great physical strength, dexterity and courage.

Within the narrative of many of these films, the independence of the strong female heroine was usually curtailed by marriage at the end of the serial, reflecting the traditional view of a woman’s inability to combine marriage and a life of adventure. However, in their professional careers the ‘serial queens’ enjoyed a lot more independence than their filmic heroines and were able to achieve just such a combination of family and professional career. Moreover, the women’s filmic accomplishments were seen not only as skills honed for film cameras, but as deep-seated character traits. Their courage was genuine.12 They were independent, fit, and daring and performed dangerous athletic feats. For American female audiences, adventure serial stars like Pearl White became models of strong modern femininity.13

As Lev Kuleshov argued in his 1922 article entitled ‘Americanism’, what most attracted Russian audiences to these and other American detective-adventure films, was their ‘maximum amount of movement’ and ‘primitive heroism’.14 While this ‘primitive heroism’ was often displayed by a female heroine, it did not lead to a formation of a primarily female fan base in Russia, unlike in America. For the male, as well as the female members of the Russian audience, these films were the only alternative to the slow, static, and psychology-driven native films made in the Russian style. The gender of the main character seemed to be of less importance than her exceptional daring and ability to perform physical stunts, along with the excitement of the suspense and fast pace of the narrative.

A group of menacing-looking American ‘Indians’ in feather headbands bring a white woman to the edge of a cliff. An intertitle announces, ‘Let her destiny be fulfilled!’ Meanwhile, a white man appears on horseback, and hurries towards the cliff with a lasso in his hands. Two ‘Indians’ drag the woman down the slope, while the white man is hurrying to her rescue, in a parallel action sequence. Another intertitle, reading ‘A race with death’, raises the perception of impending danger. The woman is pushed to run down the slope, and a huge, heavy boulder is released to roll behind her. The duration of each shot becomes much shorter (from the nine-second-long opening shot to shots lasting under two seconds each), intensifying the sense of risk and suspense. In a breathtaking wide shot, the woman runs down a steep slope, followed perilously close by the enormous boulder that is gathering speed. At the last moment, a lasso is thrown, and the woman is saved, barely escaping being crushed by the advancing boulder.

This is a scene from the second episode of The Perils of Pauline, featuring Pearl White. In this particular episode, White’s character, Pauline, is saved at the last minute by her fiancé, Harry. In many other serials, however, Pearl White’s character was not simply an adventure-seeking ‘damsel in distress’ who had to be rescued by a man, but an active pursuer of outlaws (for example, the heroine of Pearl of the Army [USA 1914]), or even a ‘good outlaw’ or a positive ‘con-woman’ herself, in dangerous pursuit of riches and treasures (for example, The Lightning Raider [USA 1919]). The episode from The Perils of Pauline described above is a good example of the ‘intensity in the build-up of the action’, ‘maximum amount of movement’, and ‘primitive heroism’ pointed out by Kuleshov.

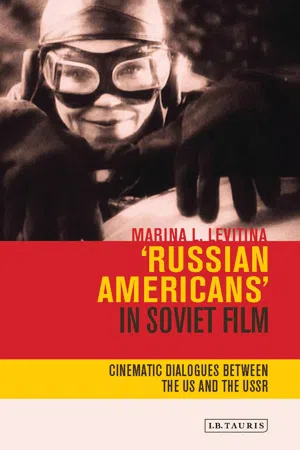

Figure 1. Pearl White driving an automobile. Wikimedia Commons

A telling article in a 1926 issue of Sovetskii ekran (The Soviet Screen) vividly describes the popularity of the films with Pearl White among the general audience in a provincial town during the Civil War:

For the first time we saw a woman as a sportsman, a horseback rider, and a boxer. [. . . ]Back then people ate little, it was a hungry time. [. . . ] There was no electricity, sunflower oil was burnt in house l...