- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

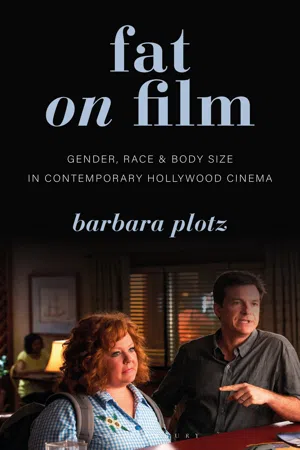

Over the last two decades, fatness has become the focus of ubiquitous negative rhetoric, in the USA and beyond, presented under the cover of the medicalized ''war against the obesity epidemic''. In Fat on Film, Barbara Plotz provides a critical analysis of the cinematic representation of fatness during this timeframe, specifically in contemporary Hollywood cinema, with an emphasis on the intersection of gender, race and fatness. The analysis is based on around 50 films released since 2000 and includes examples such as Transformers (2007), Precious (2009), Kung Fu Panda (2008), Paul Blart (2009) and Pitch Perfect (2012).Plotz maps the common cinematic tropes of fatness and also shows how commonplace notions of fatness that are part of the current ''obesity epidemic'' discourse are reflected in these tropes. In this original study, Plotz brings critical attention to the politics of fat representation, a topic that has so far received little attention within film and cinema studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fat on Film by Barbara Plotz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Critical Theorization of Fatness

Fat Studies has a sustained interest in analysing the origins and roots of modern-day fatphobia and linking those with present-day constructs and discourses of fatness. One development that in a historical perspective is seen as decisive for the beginnings of fatphobia is the establishment of the concept of normalcy in the nineteenth century. Joyce L. Huff highlights this in her investigation of William Banting, one of the first proponents of the reducing diet, who published his dieting pamphlet A Letter on Corpulence in 1863. Huff sees this new fear of the fat body as a reaction to the increasing pressure to normalize within a society that more and more relied on mass production techniques, thereby creating a physical environment based on the assumption of an average – ‘normal’ – body.1 In her argument Huff draws heavily on Foucault’s concept of disciplinary power and how its emergence at the end of the eighteenth/beginning of the nineteenth century is reliant on the concept of the norm. According to Foucault, in the disciplinary society individuals are ranked within a hierarchical order/system, dependent on how close their bodies or behaviour are to what is postulated as norm and thereby as ideal, which is how they are disciplined to conform to this postulate.2 A consequence of this development was the fascination with quantification, which allowed for the exact allocation of individuals within the hierarchy of normalization.3 Huff also draws attention to current discussions about several American airlines and their decision to charge fat passengers higher fares. She sees these decisions as prime examples of how the social imperative to conform to normalcy serves the interests of corporations – who construct our present-day environment – and negates the interests of the individual.4

These processes of normalization and quantification were relevant pre-conditions for the medicalization of fatness, a development which itself is seen within Fat Studies as decisive for present-day configurations of society’s anti-fat bias. Michael Gard and Jan Wright point out how in terms of weight, the need to quantify led to the introduction of height-weight charts by insurance companies and the invention of scales for doctor’s surgeries in the early twentieth century, which ‘allowed normality to be captured in a formula, which could be brought to bear to confirm aesthetic and moral judgments about body shape and size’.5 They also point out how the popularization of the term ‘obesity’ – which equals a certain weight with disease – contributed to the medicalization of fatness.6

The present-day biomedical and health discourse on obesity is the dominant discourse on fatness and the discourse from which all proponents of Fat Studies distance themselves. A number of medical and health professionals work on dissecting the supposedly obvious causality between ‘obesity’ and bad health, and instead propagate the ‘Health at Every Size’ (HAES) approach, which is based on the assumption that not body weight, but diet and exercise are decisive in terms of health.7 Closely related to HAES is the critical examination of how the discourses on fatness and health, exemplified by the term ‘obesity epidemic’, function and specifically how they work in terms of the marginalization and oppression of fatness.

One important argument within the field is the connection between anxieties regarding capitalism and consumerism and their displacement onto fat bodies. In his historical analysis of the beginnings of modern fatphobia Peter Stearns suggests that the rise of consumerism and the emergence of greater social and personal freedoms at the turn of the century in the United States were at odds with existing Victorian-puritan, protestant attitudes regarding self-discipline and asceticism. Consequently, the ideal of the slim body developed to compensate for these new freedoms and as a way for the individual to be an avid consumer but still display (self-)control and discipline.8 Amy Erdman Farrell agrees with this assessment and shows how in cartoons and postcards at the end of the nineteenth century not only did fat people appear as an object of mockery but they were usually depicted as members of the middle class who were excessively and tastelessly enjoying those aforementioned new pleasures and freedoms that had until then been privileges of the upper class.9 Paul Campos relates this argument to the presence and sees fatphobia as a convenient vehicle to catalyse national anxieties regarding the continued excessiveness of America and its citizens on various levels like consumerism, but also imperialism or the exploitation of natural resources.10 He also points to the fact that fat anxiety allows to make scapegoats out of those who are actually the least excessive consumers – members of the poor and working classes – and also offers a welcome opportunity to openly discriminate against other marginalized groups like African Americans, Hispanics or women. Campos suggests that the current fatphobia can be understood as ‘moral panic’, a societal phenomenon in which a group or behaviour is construed as deviant and consequently demonized as a threat to society as a whole.11 Kathleen LeBesco comes to the same conclusion and outlines in detail how the current discourse within the American public constitutes ‘fat panic’.12 Gard and Wright similarly highlight issues of morality as being at the core of the notion of the ‘obesity epidemic’ and specifically recognize the familiar narrative of Western decadence and decline being replayed in the discourse: ‘The “obesity epidemic” is, in short, a modern-day story of sloth and gluttony.’13

What enables this present-day moralization of health is the ideology of neoliberalism and specifically its paradigms of anti-intervention, individualization and responsibilization.14 While society and state are absolved of any responsibility, the neoliberal citizen is constructed as being solely in charge of their own circumstances, risks and fate. Robert Crawford points out how specifically in the US context the reframing of health as an issue of the individual was decisive not only for a rebuttal in the 1970s of prolonged attempts to establish a national health care system but also for the ideological project of responsibilization as a whole: ‘The new health consciousness became a model of and a model for what individual responsibility or its putative absence would differentially bestow and thus served as an embodied replication of individual responsibility for economic well-being.’15

The central responsibility of the neoliberal individual is that of being a responsible consumer and Julie Guthman notes how due to the conflation of eating and consumption, thinness is viewed as the embodiment of responsible consumption, and therefore takes centre stage within contemporary discourses of health. She also highlights the contradictions of the ideal neoliberal subject being an enthusiastic consumer while at the same time being expected to display a high level of self-control and how spending money on being thin constitutes the perfect solution to these potentially conflicting imperatives.16

Kathleen LeBesco draws attention to how fat citizens are constructed not only as failed consumers but also as inadequate workers, who are unable to fulfil their duty as productive members of a capitalist economy.17 In the United States these discourses have become very explicit over the last decade, as can be seen in various governmental campaigns that openly declare a ‘war on obesity’ and decidedly link patriotism with slimness. Next to the alleged costs of obesity-related illnesses for employers, these campaigns focus heavily on the large part of the national health care costs for which obesity is supposedly directly responsible, thereby constructing fat individuals as a liability to the state and establishing slimness as a precondition for being a proper American citizen. Accordingly, in 2001 then Health and Human Services Secretary Tommy G. Thompson proclaimed that ‘all Americans – as their patriotic duty – [should] lose 10 pounds’.18

Foucault’s concepts of biopolitics and biopower are often applied within Fat Studies in order to explain and analyse these discourses of obesity and citizenship. In A History of Sexuality Foucault describes how from the seventeenth century on the modern state increasingly began to consolidate its power via the control of life as opposed to the control of death, which used to be the practice previously, in the state ruled by an absolute sovereign. This control of life consists of, on the one hand, the disciplining of the individual’s body and, on the other hand, the regulation of the body of the population as a whole.19 Foucault emphasizes that this focus on life does not entail a higher regard for people’s right to live or well-being and points to discriminatory practices like racism, which are based on the exclusion – or even killing – of certain members of a state’s population based on the justification that they are supposedly endangering the life of the population as a whole.20 One of the main characteristics of this biopower is the fact that it is productive as opposed to the repressive sovereign power. ‘Hence there was an explosion of numerous and diverse techniques for achieving the subjugation of bodies and the control of populations, marking the beginning of an era of “biopower”.’21 The discourses regarding the ‘obesity epidemic’ and the knowledges and practices it produces are a contemporary example of the workings of biopower and biopolitics.22

April Michelle Herndon observes how these discourses never mention the costs of fatphobia to fat people – due to e.g. discrimination on the job market or higher health insurance rates – and also specifically target social groups already in danger of being discriminated against, namely the poor and working classes, people of colour and immigrants.23 Herndon, Campos and LeBesco, among others, all agree on the fact that this is evidence of a sublimation of certain t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Series Editors’ Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 A Critical Theorization of Fatness

- 2 The De-Masculinized Fat Male

- 3 Female Fatness as Non-Normative Femininity

- 4 The Funny Fat Body: Slapstick and Gross-Out

- 5 The Fat Eater: Food and Eating

- 6 The Fat Outsider

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Filmography

- Index

- Imprint