- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Greater Flamingo

About this book

A detailed monograph on an iconic bird of tropical wetlands around the world, the flamingo.

With their curious feeding behaviour, peculiar elongated body, gregarious social lives and exotic pink plumage, flamingos are among the most familiar and popular of all the world's birds. They have inspired artists, poets and amateur naturalists for centuries, but until 50 years ago very little was known about their biology.

A growing number of scientists have directed their attention to these magnificent birds over recent years; this book summarises current understanding of flamingo biology, with detailed discussion of population dynamics, ecology, movements, feeding, breeding biology and conservation, with emphasis placed on the authors' work on the famous population of Greater Flamingos in the Camargue region of southern France.

There is also a detailed guide to breeding areas, and an outline of future challenges for research.

With their curious feeding behaviour, peculiar elongated body, gregarious social lives and exotic pink plumage, flamingos are among the most familiar and popular of all the world's birds. They have inspired artists, poets and amateur naturalists for centuries, but until 50 years ago very little was known about their biology.

A growing number of scientists have directed their attention to these magnificent birds over recent years; this book summarises current understanding of flamingo biology, with detailed discussion of population dynamics, ecology, movements, feeding, breeding biology and conservation, with emphasis placed on the authors' work on the famous population of Greater Flamingos in the Camargue region of southern France.

There is also a detailed guide to breeding areas, and an outline of future challenges for research.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Greater Flamingo by Alan Johnson,Frank Cézilly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

Flamingos, like geese, cranes and other colonial waterbirds, are very eye-catching, whether foraging in large numbers or flying in skeins. However, they differ in many ways from other large wading birds in their preference for salty wetlands, their manner of feeding by filtering and their habit of raising their chicks in a nursery, or crèche. They are fascinating birds to observe, and have always been of great interest to birdwatchers and researchers alike. Standing among the most popular bird species, they are considered as a flagship for wetland conservation. Great progress in our understanding of the life history of flamingos has been achieved over the last twenty years, thanks to unique research and conservation efforts. The aim of the present book is to provide the reader with an updated review of the current knowledge.

It is not known precisely how many Greater Flamingos exist in the world, but reports of decreases in numbers in some areas are counter-balanced by increases in others, and from all available evidence, their overall numbers, roughly half a million, have not changed radically in recent decades. Since historical times, people have been fascinated by flamingos, even in countries where they do not occur in the wild, and their presence on particular wetlands has sometimes motivated the legal protection of an area. The species is protected throughout much of its range, as are many of the more important wetlands on which flamingos occur, but several of these areas remain unprotected and the species' future will depend on our capacity, and that of future generations, to conserve these sites.

FLAMINGOS AND MAN

The extent to which the flamingo has always held a place in the human imagination has been described in previous works (Allen 1956; Kear & Duplaix-Hall 1975; Ogilvie & Ogilvie 1986) and need not be re-explored here. The flamingo is portrayed in cave paintings at Tajo de las Figuras, Cádiz, in Andalusia, Spain, which date from the Bronze Age 5,000 years BC (Gurney 192 1; Topper & Topper 1988; Mas Cornellà 2000). It also figures frequently in Carthaginian, Byzantine and Greek art and was occasionally portrayed as a hieroglyph by the early Egyptians to mean the colour red (Houlihan & Goodman 1986). Early flamingo representations are also preserved on a large number of decorated predynastic ceramic vessels from the Gerzean Period (Naqada 11) of Ancient Egypt, 3500-3200 BC.

Part of man's fascination with flamingos is clearly attributable to their colourful appearance. The generic name Phoenicopterus is derived from the Greek and means scarlet-winged. In many languages, the common name directly refers to the flamboyance of flamingo wings (see Carro & Bernis 1968). All flamingo species are highly gregarious, with colonies of Greater Flamingos regularly exceeding 10,000 pairs and those of Lesser Flamingos sometimes exceeding 1,000,000 pairs. The spectacle of thousands of these birds taking wing cannot help but leave an impression on anyone lucky enough to see it. However, it is not colour alone that sets flamingos apart from other birds. Their behaviour is also quite distinctive, and flamingo displays provide one of the most impressive of avian spectacles. Considering the unique features of the species, above all the bill structure, Chapman & Buck (19 10) even suggested that they might almost be regarded as a separate act of creation!

Their choice of habitat is also unique, because in many parts of their range flamingos inhabit highly saline and/or alkaline lakes, where conditions are generally too harsh for other species, including man. Many of these areas are remote and inhospitable to humans, which is certainly why the Lesser Flamingo's breeding colonies were not discovered and described until 1954 (Brown & Root 1971). Just three years later, the James' Flamingo, which since the beginning of the century had been presumed extinct, was rediscovered in the high Andes, where it occurs mainly at altitudes above 4,000 m (Fields; & Krabbe 1990).

In the past, persecution and disturbance-in the form of hunting the birds for their flesh and raiding colonies for eggs-probably had a strong effect on the numbers and distribution of flamingos, at least throughout the Mediterranean region and in parts of Asia. The Romans are reputed to have banqueted on flamingos' tongues, which they considered a delicacy (Allen 1956), while Babar the Great (1483-1530) reportedly breakfasted on their eggs, which he collected at Lake Ab-e-Istada in Afghanistan (Paludan 1959). Recipes for the species are not difficult to find in early French, Italian and Spanish culinary literature, reflecting the prevalence of flamingo hunting throughout the Mediterranean (de Marolles 1836). Flamingos were shot in the Guadalquivir Marshes in southern Spain in large numbers well into the 1960s, while French law did not give full protection to the species until as recently as 1976, although it had been illegal to shoot flamingos since 1962. Such pressures must have driven the flamingo to nest in only the most remote places.

Remarkably, this situation has now changed, at least in the western Mediterranean, and the flamingo is no longer the wary bird it formerly was. This change of behaviour has had an impact on the species' distribution, both during and outside the breeding season. Wild flamingos can currently be found feeding in close proximity to humans, or even being fed by humans, as for example in Dubai Creek in the UAE and at the ornithological park at Pont de Gau in the Camargue. The species has increased in number throughout the Mediterranean region as a result of effective protection measures and multiple conservation efforts, and, also quite remarkably, flamingos even breed now in the suburbs of a large city, at Cagliari in Sardinia. Saltpans have probably played a major role in determining the present distribution and numbers of flamingos, at least in the Mediterranean region, and they have received considerable attention in this book (Chapters 2 and 10). However, despite these successes, it seems that the species' distribution, in particular that of the Greater Flamingo, is more restricted today than was that of its ancestor species (Feduccia 1996).

INTEREST IN FLAMINGOS: RECENT HISTORY

The second half of the 20th century saw an upsurge of interest in flamingos. On one hand previously unknown breeding areas were discovered, often in remote areas, or poorly documented colonies were revisited, and much new data were gathered on flamingo numbers and distribution; on the other hand, desk or laboratory studies were undertaken, the results of which stand as empirical works which anyone with a serious interest in flamingos will have on their bookshelves. In the first instance, Etienne Gallet and Leslie Brown, for example, who studied flamingos respectively in the Camargue (Gallet 1949) and in the Rift Valley lakes of East Africa (Brown 1975), are just two of the naturalists who made valuable contributions to our knowledge of flamingo breeding biology in the wild. Other references to breeding, dating back to the end of the 19' and the first half of the 20' century, can be found in Yeates (1950). In the second period, significant contributions came from Robert Porter Allen's field trips and desk study into the life history of all species of flamingos (Allen 1956) and from the remarkable paper by Jenkin (1957) on the diet and very specialised way in which flamingos of all species feed. This latter study was so meticulous that it seems destined to remain, even despite more recent accounts (Zweers et al. 1995), a constant source of reference for anyone wishing to learn more about flamingos' unique manner of feeding, which we ourselves have not studied in detail. Many of these works are no longer readily available, but they are not necessarily outdated and we hasten to recommend them still to readers according to their field(s) of interest. We have widely consulted them, and other 'classic' flamingo studies, in writing the present work. However, the longest-running study of flamingos in the world, and one of the longest for any bird species, was begun in the Camargue over half a century ago.

FOCUS ON THE CAMARGUE

Luc Hoffmann was still a student when in 1947 he began chasing flamingo chicks in the Camargue in order to ring them. This was the very beginning of a study aimed at finding out more about the biology, movements and longevity of these birds in the Mediterranean region. Over the following decade, breeding was closely monitored and the ringing programme improved and intensified, until, in the early 1960s, flamingos stopped breeding in the Rhône delta. During seven long years, no chicks fledged from the Camargue and there was much concern over the Greater Flamingo's future in France and elsewhere in southern Europe.

In spite of their extensive rang-e across southern Europe, south-west Asia and Africa, Greater Flamingos were nesting in only about 30 localities, one of the more important of these being the Camargue. This is certainly one of the best-documented colonies, since records of occasional breeding in the region date back to the mid-16th century (Quiqueran de Beaujeu 1551; Darluc 1782) and quite regular, albeit not annual, breeding had been reported since the beginning of the 20' century (Gallet 1949). The origins of the main conservation problems which had arisen in the Camargue were quite well understood because they had been identified by Gallet (1949) and confirmed by Hoffmann in the 1950s: erosion of the breeding islands, disturbance from various sources during breeding, particularly by aircraft, and predation of eggs and chicks by Yellow-legged Gulls, which were rapidly increasing in number throughout the region. Initiatives understandably moved away from research towards conservation and management.

For conservationists it was a great relief when in 1969 over 7,000 pairs of flamingos recolonised the Camargue, mostly at the Etang du Fangassier, and raised chicks for the first time since 1961. Breeding was highly successful, owing in no small part to wardening by staff of the Tour du Valat Biological Station, which Luc Hoffmann had established in the 1950s in the heart of the delta. There were high hopes that the flamingos would nest again regularly, and over the following years this optimism proved to be justified. Conservation and management efforts initiated by the Tour du Valat in the 1960s and 1970s, which included building a breeding island, paid off and gradually the Etang du Fangassier became the flamingo sanctuary it is today. Since that epic event of 1969, flamingos have nested every year in the Camargue, and from 1972 onwards only at the Etang du Fangassier. Threatened in the 1960s the Greater Flamingo, emblem of the Camargue, made a remarkable recovery, so much so that numbers have increased beyond those projected by the action plan, and the species has become the most abundant aquatic bird breeding in the Rhône delta. This may be seen as a positive development with regard to the species' conservation, but it has also resulted in as the birds now cause crop damage by feeding in rice fields in spring, and they are understandably not too popular with the unlucky farmers. Flamingos are now quite accustomed to human activity, including the disturbance caused by aeroplanes, and in some places are now remarkably confiding. This change in behaviour, associated with a population increase and overcrowding at the sole breeding site in France, has driven birds to colonise new areas in the western Mediterranean in the 1990s, in some of which they now breed.

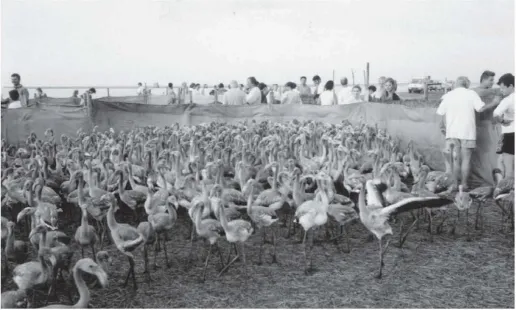

The flamingo's new-found security is due in no small degree to Luc Hoffmann's decision to warden the colony when breeding resumed in 1969. Once breeding was securely re-established, in 1977, the marking programme was reactivated (Figure 1). The advent of laminated PVC enabled us to mark birds with large coded leg-bands which allow individual recognition in the field. A band observation programme was begun both locally aid internationally, to which many amateur ornithologists were soon to contribute. In 1986, colleagues in Andalusia launched a similar conservation and research project on a regular basis at the Fuente de Piedra Lagoon (Málaga), 950 km south-west of the Camargue. The success of this colony, combined with the collection of much new data, and concern for the conservation of flamingo habitats throughout the western Mediterranean and north-west Africa, led to the organisation of an international workshop on flamingos which was held at Antequera (Málaga) in 1989 (Junta de Andalucía 1991). More recently, with flamingos breeding in Sardinia and on mainland Italy, the capture-recapture study has been further expanded to include partners in 1tak. At the time of writing, an extension of activities is envisaged to sites beyond the western Mediterranean which are poorly covered at present.

Figure 1. Capture and ringing of chicks. Between 500 and 900 flamingo chicks were captured annually for marking just prior to fledging once a year in the Camargue for over a quarter of a century. The subsequent observations of these individuals have provided the material for the study of these birds in the wild. Similar capture and marking operations, involving hundreds of people, are organised most years at breeding sites in Spain and Italy. (J-P Taris).

Multiple resightings of many thousands of flamingos have provided the basis for the study of the ecology and dynamics of the west Mediterranean sub-population of Greater Flamingos, which represents about one-fifth of the world population. Flamingos have a potentially long life expectancy, with some captive birds exceeding 60 years of age. Of those flamingos PVC-banded in 1977, one-fifth were seen back at the Fangassier colony at 20 years of age, and given our most recent estimates of adult survival, a few of those birds ringed by Luc Hoffmann in the 1950s may well still be around today!

The Camargue flamingo study has evolved as both a research and a conservation project and we have endeavoured to give adequate attention in this book to the conservation needs of these birds, while at the same time presenting the results obtained from a scientific project which we plan to pursue in the future. Management techniques which have been so successful in France and Spain could easily, where appropriate, be applied in other parts of the world. We have attempted to minimise the bias towards the Camargue but, since this area has been the theatre of such a great effort, we hope that the reader will forgive us if we have not been entirely successful in doing so.

The Camargue is one of the few places, if not the only site, in the world where flamingos breed every year, and have done so for more than 30 years now. Breeding was not so regular in the first half of the 20th century, as anyone who reads Gallet (1949) or Yeates (1950) would soon realise, and this situation is clearly anthropogenic. In addition to the effective conservation and protection of the breeding and feeding areas required to sustain a flamingo colony, annual breeding is possible because of the semi-permanent water levels of the saline lagoons which have been created and maintained by the salt industry. However, the wind of change is now blowing through this semi-agricultural industry and the Greater Flamingo's future in the Mediterranean may depend to a large degree on the survival of the historic saline complexes.

THE FLAMINGO SPECIALIST GROUP

Both individual and group initiatives undertaken during the 20th century led to a growing interest in flamingos and in particular the conservation of a species that was popular yet little studied in the wild and increasingly threatened. In 1971, the Flamingo Specialist Group was established by the former International Council for Bird Preservation (ICBE now BirdLife International) primarily in the interests of flamingo conservation (Johnson 2OOOb). One of the first initiatives of the group was to undertake, in the 1970s, a practically worldwide survey of flamingos of all species (Kahl 1975b), to update knowledge on distribution and on population estimates made earlier by Brown (1959). At the same time, the group convened a Flamingo Symposium which was held at The Wildfowl Trust (now Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust) in Slimbridge (UK) in July 1973. This was the occasion for field ornithologists to unite with ethologists such as Adelheid Studer-Thiersch, whose behavioural studies have been, and still are, carried out at the Base1 Zoo (Switzerland). The proceedings of this meeting were published as one ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1: INTRODUCTION

- 2: THE FLAMINGOS

- 3: RESEARCH

- 4: DISTRIBUTIOANND NUMBERS

- 5: MOVEMENTS

- 6: FORAGINGECOLOGY

- 7: MATINGSYSTEM AND MATE CHOICE

- 8: BREEDINBGIO LOGY

- 9: SURVNAALN D RECRUITMENT

- 10: CONSERVATIOANND MANAGEMENT

- 11: CONCLUSIONWSH: AT DOES THE FUTURE HOLD?

- 12: AN INVENTORY OF THE MORE IMPORTANT GREATER FLAMINGO BREEDING SITES

- Appendices

- Glossary

- References