![]()

1

Welcome to Development Hell (A.K.A. What the Hell Is Development?)

“ Can’t you just develop the ideas that will get commissioned?

—Executive Producer (Anon.)

A couple of years ago, I saw a video of a creative session held at a big UK broadcaster: the kind of session that reassures senior managers that their organization is on the creative cutting edge. The video showcased all the programs that creative facilitators had helped through the “development” process, but the clips were from programs already in production (some had been on air for years). Whatever the creative facilitators were doing it wasn’t program development. For a moment I was baffled, and then I had a revelation: few people understand what program development is.

So what is it?

The development process starts when you have an idea and it stops when a TV channel has agreed the budget and editorial content and has given the project the greenlight to go into production. Before any program, let alone an international hit such as Deadliest Catch, American Idol, Planet Earth, or Supernanny, hits our television screens it has probably spent months, if not years, in development; being turned from a vague concept into a workable format. Before it reaches the pitch stage, an idea needs a clear narrative, suitable talent (a presenter or host) attached, access secured, a proposal written, and a pitch tape shot. However, the development process doesn’t always happen in that order: your starting point might be onscreen talent for whom you have to find a format; a blank page with a tight deadline; or sometimes even a commission. Often, you will make a taster tape, other times not; mostly you will pitch in a formal meeting, but you might find yourself pitching in a corridor; you need to write a proposal but it may never be read. And the program that ends up on screen will be different from the one you pitch, and may be unrecognizable from your original idea.

Everyone believes that to be successful in development you have to have good ideas, but the truth is that development is not just about coming up with good ideas. It’s about market forces, audience trends, and channel executives’ foibles. Development is about more than mere creativity. “It’s about the timing, your relationships with the commissioners, it’s about being one of the ‘in’ companies,” says one development producer. “It’s about getting past commissioners’ PAs and being able to convince them to meet you. It’s about being able to cater to what that channel wants, and it’s not always about how good your idea is.” Development is, in other words, all about the politics.

Independent production companies survive by selling ideas and TV broadcasters wouldn’t exist without a ready supply of programs—so who are the people who are keeping the TV business alive?

Who’s Who in Development?

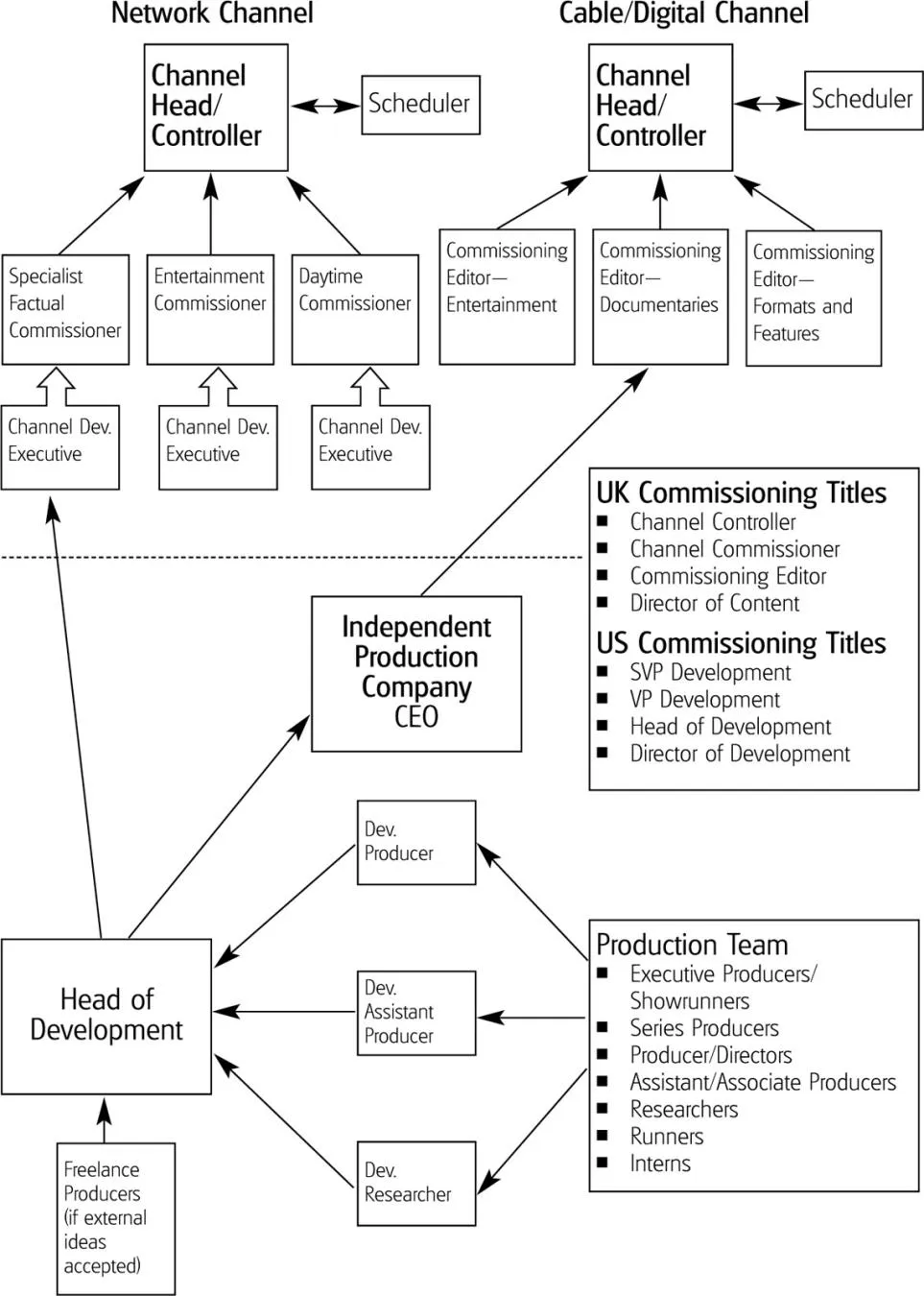

Most independent TV production companies dedicate staff to the development of new program ideas (some TV channels also have an in-house development team); in a small company it might be one person, or in a larger company it’s more likely to be a team of people. The team is lead by a head of development who reports to the company’s creative director, managing director, or CEO (every company uses different titles). Working under the head of development is a team of producers, assistant/associate producers, and researchers. The team members might work individually (in their own specialisms, such as science or history) or together as a team. Team members regularly pitch their ideas to the head of development, who decides which ones should be developed further. The head of development then pitches those ideas to the head of the company, who decides which of those ideas should be pitched to the TV channels. In some companies the head of development conducts meetings with the channels, in other companies the managing director pitches the ideas. The executive or series producer penciled in to make the program may or may not be involved in the development and pitching process.

In a well-run team everything should run relatively smoothly with well-targeted ideas being developed, pitched, and commissioned on a regular basis but, inevitably, it’s not that simple. Staff turnover in development can be high and the people charged with coming up with the next big idea are often the least knowledgeable about how the business works. “I just thought it would be that I would have a good idea and develop it a bit and then it would be commissioned,” says one producer/director. “I really did think it would be as straightforward as that: I was very naïve!”

Development is a discipline that requires an in-depth knowledge of the industry. As most programs take many months to go from idea to commission, the people with the best chance of success are those who have strong, ongoing relationships with the channel executives: their potential buyers. In other words, to be successful you need to be committed over the long term.

Development also requires a set of skills that are distinct from those of production. It can be hard for production people to get into the unique mindset needed for development—selling rather than making—and many find it immensely frustrating. One experienced producer/director who made technically difficult and emotionally demanding medical series said, “Development is the hardest job I’ve ever done,” before fleeing back to the safety of production.

Filmmakers—understandably—want to make programs about issues they are passionate about, and channel executives want high audience figures in order to attract advertisers (read: funding). Unfortunately passion projects aren’t always ratings winners, therefore, development producers have to balance pitching ideas they love with those they think will sell; alas, they will not always be the same thing.

Who’s Who at the Channels?

Once an idea has attracted initial interest from a channel executive, the idea enters the channel’s development process. Channels all have different development and commissioning structures. At some, particularly in the UK, network commissioners have their own budget and look after a specialty, for example, daytime or specialist factual (science, history, arts, religion, natural history) programs. They make a decision about whether your proposal fits their brief, and if so, work on it with you until they are happy to formally commission it (usually after they’ve obtained a confirmatory “twin tick” from their channel controller).

At other channels, particularly US cable channels, a team of channel executives (usually known as VPs/development), filter all the proposals that come into their office. The channel executives are the vital link between you and the people with the power and money to greenlight or reject your idea. They individually take pitches from producers and then pitch the ideas they like to the rest of their team on a weekly basis. As a team, they decide which ideas to pitch to the channel head and other senior decision-making executives, such as the scheduler and business affairs executive, at a regular commissioning or “greenlight” meeting. It’s a competitive environment and an individual executive’s reputation rests on pitching the most attention-grabbing idea, so they have to make sure that every idea is properly developed before they expose themselves to the gladiatorial arena of the channel pitch meeting. The senior executives are unlikely to have read your written proposal so your fortune rests on the shoulders of your channel development executive.

Cultivating a good relationship with a channel executive is the single most important thing you can do, and the more important they are in the channel hierarchy the better. “The truth of it is: once you’ve got a good idea, it’s all about knowing the right people at the channel or you won’t close the sale,” says Ed Crick, Managing Director, Bullseye (and former director of development, TLC). But it can be hard to keep track of the channel executives, as commissioning can seem like one long round of musical chairs. “It pisses me off, how one minute you’ll see [a commissioner] at a briefing and they’re so committed to their channel,” says a UK-based development producer, “and then two weeks later you see they’ve gone to a different channel, and you think hold on, where’s your loyalty?”

As you’ll find out, this tension between development producers and channel executives is never far from the surface. “TV is a funny industry in that no one is sure who has the higher status,” observes filmmaker Adam Curtis. “The producers think they have more dignity than those who commission, but to be brutal, over the last ten years the commissioners have proved to be more creative than a lot of the producers.”

The Commissioning Chain

Follow the arrows to see the path that an idea might take through an independent production company development team and channel commissioning structure in order to reach the person who can ultimately give it the greenlight. NB: every channel is structured differently and has different titles for similar jobs.

Development Master Class 1

Know Who’s Who

1. Google the names of the channel head/controller of your five favorite channels.

2. Go to the channel websites and find out who the commissioning/ development executives are in the genre of programming that most interests you.

3. Sign up for the weekly newsletter at www.tvmole.com to keep up to date with who is in and who is out in the world of development and commissioning.

4. Start a contacts book or online database. Become familiar with the names of people working in independent production company development teams or in the channel commissioning structure. Update your database every time they move jobs so you can keep track of who’s who.

5. Join a professional association and start networking with senior people in the industry. For example, Women in Film and Television has more than 10,000 members in forty chapters around the world.

Explore More

Visit tvmole.com to see who currently works where in commissioning and development in the UK and USA:

for heads of development at independent production companies:

http://tiny.cc/headdev; for channel executives at channels in the UK and USA, visit:

http://tiny.cc/channelcommissioners.

![]()

2

Do You Have What It Takes?

“ You’re obviously suffering from delusions of adequacy!

—Alexis Carrington, Dynasty

“ When Mark Burnett was a British paratrooper fighting for his country in the Falklands War it would have seemed implausible that one day he would wind up working as a nanny in Beverley Hills and then selling $18 T-shirts on Venice Beach, LA. It would have seemed even more improbable that, fewer than twenty years later, he would have a reported net worth of around $300 million. How did he go from beach bum to multimillionaire? By selling TV programs.

Mark Burnett, award-winning US producer of Survivor, The Apprentice, and Are You Smarter than a Fifth Grader?, is one of the world’s most successful TV producers, and has been named as one of Time magazine’s “100 Most Influential People in the World Today.” He’s so prolific—having produced more than 1,100 hours of television, which air in more than seventy countries—that he is the first reality producer to receive a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame. Tellingly, he’s not just won TV industry awards, but also won Brandweek’s Marketer of the Year award.

In 1993, Burnett, thirty-three years old and fresh out of the army, satisfied his taste for adventure by participating with an American team in an extreme race called Raid Gauloises in Oman. The race involved traveling in teams of five over hundreds of miles by camel, horse, and on foot. This trip started a journey that led to Burnett being credited with creating one of the most watched television shows of all time, which regularly pulled in more than twenty million viewers.

At first glance, it seems that nothing in Burnett’s background predicted his television success, but in fact everything he did foreshadowed it. When working in the army he learned to make decisions under pressure; while working as a nanny he was exposed to influential people and when selling his T-shirts he developed a talent for pitching for business. Burnett also found time to work in insurance and had a credit card marketing business, which taught him about demographics and consumer attitudes. He’d also raised sponsorship that helped turn his Raid Gauloises adventure into a series of extreme adventure competition television programs called Eco-Challenge.

Taken separately, this seems like a disparate set of skills, but together they prepared him to pitch an idea for a new television show to CBS.1 Burnett suggested putting sixteen strangers on a desert isla...