eBook - ePub

The Skylark

About this book

The Skylark is one of Britain's most popular and inspirational birds, and in recent years it has also been one of the most newsworthy.

The species' population has plummeted as a consequence of changes in farming practice, and the RSPB has launched a major research and fund-raising campaign to save the 'blithe spirit' from further decline.

This book looks at all aspects of the life of the Skylark, from its biology, migratory patterns, breeding behaviour and habitat requirements, to its role in legend and folklore. It also discusses its recent rapid decline which has led to the species being placed on the top-priority 'red list' of Birds of Conservation Concern by the leading governmental and non-governmental conservation organisations in the UK.

Three closely related species, Oriental and Japanese Skylarks and the enigmatic Raso Lark are also discussed.

The species' population has plummeted as a consequence of changes in farming practice, and the RSPB has launched a major research and fund-raising campaign to save the 'blithe spirit' from further decline.

This book looks at all aspects of the life of the Skylark, from its biology, migratory patterns, breeding behaviour and habitat requirements, to its role in legend and folklore. It also discusses its recent rapid decline which has led to the species being placed on the top-priority 'red list' of Birds of Conservation Concern by the leading governmental and non-governmental conservation organisations in the UK.

Three closely related species, Oriental and Japanese Skylarks and the enigmatic Raso Lark are also discussed.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Hoopoe-Lark in display flight

CHAPTER 1

The larks

There appears to be no other passerine family that equals the Alaudidae in successful desert occupancy, as regards the numbers of species filling a variety of desert niches. It is tempting to speculate upon the basis for this adaptive success of the larks in the desert environment.

Ernest J. Willoughby (1971)

Larks are the favourites of few birdwatchers. They tend to be dully-plumaged, difficult to find and identify, and reach their greatest variety in austere habitats occupied by relatively few other species. Yet, on closer acquaintance, the larks are an unexpectedly diverse and interesting family.They have successfully conquered some of the most hostile environments on the planet. In a few places, in fact, they are the only birds capable of surviving. Their superficial uniformity belies a huge variation between the different species in population, distribution, behaviour, structure and ecology. The songbird species with the largest and the smallest natural geographical ranges in the world may both be larks (the Horned Lark and the Raso Lark respectively). In many respects, the larks are one of the most diverse families of songbird in existence. Yet despite this diversity, there are strong enough similarities between the different lark species to bind them into a very distinct group. This chapter introduces the larks, their variation, distribution and ecology, to identify generalities within the family that will help us better to place the Skylark in the context of its relatives and its environment.

DISTRIBUTION, HABITATS AND NUMBERS

Larks are found from the Arctic tundra to the South African veldt, and from the prairies of North America to the Australian outback. In virtually any open habitat outside the Americas, the larks form a distinctive and often conspicuous part of the bird community. Yet within this range there is a huge variation in patterns of distribution.

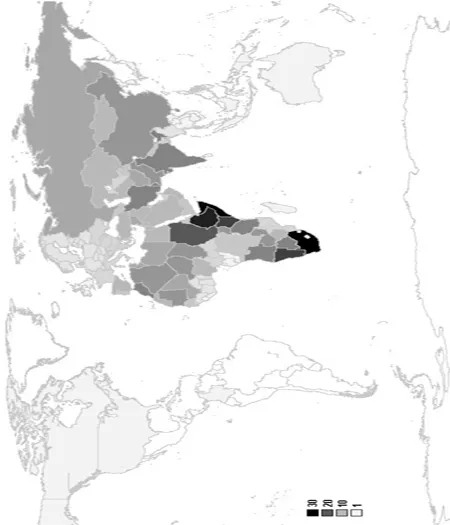

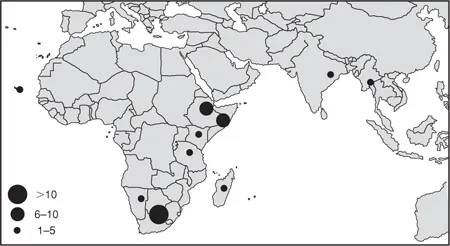

The diversity of lark species is greatest in two relatively restricted arid and semiarid areas in Africa (Figure 1.1). The northeast arid zone (Somalia and Ethiopia) and the southwest arid zone (Namibia and the Karoo) are both centres of high lark endemism and species richness. In the latter zone, the larks exhibit a higher rate of endemism by area than is found in any other family of birds in Africa (Dean &Hockey 1989), and South Africa hosts more endemic species of lark than any other country (Figure 1.2). Nine species are endemic to Somalia and Ethiopia, and several more are close to being endemic to the Horn of Africa, their ranges just extending into northern Kenya. The high diversity of species in these areas is due to two factors: a long natural history of open habitats, providing the evolutionary time necessary for adaptive radiation, and a high diversity in topography, soil type, vegetation and climate patterns, which create a mosaic of different open habitats within a relatively small area. It is also possible that the paucity of other songbirds in these austere environments has reduced competition and so allowed the larks to radiate into all the available niches. As MacLean (1970) and Willoughby (1971) have pointed out, no family of passerine birds has shown as great an adaptive radiation in the arid regions of the Old World as have the larks.

Perhaps not surprisingly for a family of African origin, larks are poorly represented in the New World by just a single species1, the Horned (or Shore) Lark, which, in the absence of competition from other larks, occupies a very wide range of habitats across North America and is extremely common. The Horned Lark is also the only lark to have penetrated the tundra zones and many alpine regions. The only Old World regions from which the larks are wholly absent are the forested boreal zone and uninterrupted expanses of tropical rainforests. With the exception of a small and isolated population of Horned Larks in the Colombian Andes, the larks are absent from Central and South America. The meadowlarks, which in the New World fill a similar niche to larks, are only distantly related. In Australia and Madagascar, the larks are again represented by single species, each of which occupies a very wide range of open habitats. The absence of speciation in Australia, which has very large areas of varied open habitats, might be due to the relatively recent arrival of the family on the continent. No larks occur naturally in New Zealand.

Figure 1.1. The distribution of the world’s lark species. The depth of shading indicates the number of species breeding in each country.

Figure 1.2. The distribution of the world’s single-country endemic larks.

Larks are primarily birds of open habitats, with or without patches of taller vegetation, and most species nest on the ground. There are no true woodland species, although some, such as the Woodlark, inhabit the open spaces between patches of woodland and live in close proximity to trees. The two large, thrush-like Pinarocorys larks of the African savannahs frequently perch in the tops of trees, but all species feed almost exclusively on the ground. Other species shun trees and taller vegetation altogether and many reach their highest numbers in habitats totally devoid of trees. A few species, such as the Dune Lark, seem capable of surviving in habitats that are almost devoid of vegetation of any sort.

Within their given habitats, larks often occur at rather low densities. Many natural open and arid habitats, such as deserts, steppes and savannah, are biologically rather unproductive, food is scarce and bird densities therefore low. However, since these habitats can cover huge areas, some of the larks are very numerous. The Horned Lark, which nests across most of the world’s tundra regions and throughout much of North America, is one of the most abundant birds on the planet. In certain arid habitats, the larks can make up a large component of the total bird community. In the steppes around Lake Baikal in Siberia, for example, over half of all the individual birds present, and the two commonest species, are larks (Sharaldaeva 1999). In the semi-deserts of the Caspian region, the larks again form the numerically dominant bird group (Shishkin 1982).

Perhaps because they tend to inhabit arid landscapes with low human population density and pressure, the larks as a family contain a lower proportion of endangered species (around 8%) than the average across all bird species (around 14%). There have been no recorded extinctions of larks in the last few hundred years (Fuller 2000). However, some species are extremely rare and have very small ranges, and eight species are now listed by IUCN as Globally Threatened (Birdlife International 2000). Two of these are in the highest Critically Endangered category, placing them amongst those bird species most likely to become extinct within the next few decades. The enigmatic and peculiar Raso Lark (Plate 3) of the Cape Verde Islands has one of the smallest ranges and populations of any bird in the world, with often fewer (and sometimes far fewer) than 100 individuals eking out an existence on a tiny, barren islet of less than 7 km2. In January 2003, the total population of this species was 98 individuals, of which only 30 were females. After long periods of drought, the population of this species may have fallen to fewer than ten pairs (Donald et al. 2003). The other Critically Endangered species is Rudd’s Lark, a rare and little-known upland grassland specialist from South Africa, where it is threatened by loss of natural grasslands to agriculture (Hockey et al. 1988, Barnes 2000). Ash’s Lark and Botha’s Lark are placed in the second highest threat category, Endangered, and four species are listed as Vulnerable. Each of these eight globally threatened lark species is endemic to a single country.

Some larks remain virtually unknown. Ash’s Lark, discovered as recently as 1981 in coastal Somalia, is known only from the original sighting, and the Degodi Lark, discovered in southern Ethiopia in 1971, is not much better known. Equally elusive is Archer’s Lark, first found in a strip of grassland in western Somalia in 1920 and subsequently at another site. It has not been seen at the original location since 1922, or at the subsequent site since 1955, although this may better reflect the political situation, and therefore the number of visiting ornithologists, than the species’ rarity. The number of threatened species seems set to increase as taxonomic research continues to identify new groups of often rare species within what were previously regarded as single common species.

EVOLUTION AND TAXONOMY

Despite their superficial uniformity, the larks (which are taxonomically placed in the family Alaudidae) are one of the most distinctive and diverse groups of songbird in existence today. The first ancestors of the songbirds (or passerines) probably evolved on the ancient southern landmass of Gondwanaland, in what is now Australia (Barker et al. 2002). From here they spread and radiated throughout the world, and modern songbirds now comprise around half of all the planet’s bird species. The larks themselves probably started to diverge from other songbirds in the Ethiopian region of eastern Africa, and the family still reaches its greatest diversity in that continent. The earliest larks are recorded from fossils dating from the middle of the Miocene, around fifteen million years ago, although the earliest fossils that can be attributed to modern genera or species are far more recent, dating from the late Pliocene and early Pleistocene, less than two million years ago. Skylarks or their ancestors were already present in Europe during the Pleistocene (Harrison 1988, Tomek 1990). The major centres of lark radiation in Eurasia were probably the steppes of eastern Europe and southwestern Asia and the semi-deserts of the Mediterranean.

The larks have uncertain affinities with other songbird families, but certainly no close relatives. They differ from all other songbirds in the structure of the syrinx, the bony-ringed resonating chamber at the lower end of the windpipe that is unique to songbirds. The syrinx of larks is distinctive in that it lacks a bony pes-sulus, a bar that lies across the top of the convergence of the bronchi, and has only five sets of muscles, as opposed to the six to eight of other oscine songbirds. A further distinction is that the back of the tarsus (the longest leg bone) is rounded and covered with small scales (or scutes), rather than having the larger, smoother and more sharply edged scales of other songbirds. These apparently trivial anatomical distinctions actually indicate that the larks have been following a lineage separate from that of the other songbirds for a very long time. The moult strategy of larks is unusual (though certainly not unique) among non-tropical songbirds: adults have a complete, rather than a partial, autumn moult, with no spring moult, and juveniles have a complete post-fledging moult. Head-scratching behaviour, previously thought by some taxonomists to be of importance in assessing the relatedness of different bird families, is indirect, the head being scratched over the partially outstretched wing.

Larks have traditionally been regarded as one of the more basal (or ‘primitive’) groups within the modern passerine assemblage, and thus are generally placed near the start of the passerines in taxonomic lists (and therefore in field guides in which birds are arranged in taxonomic order). However this view is now being challenged. Although they have ten primary feathers, the larks may be taxonomically closer to the nine-primaried songbirds, which include the buntings and finches, because of similarities in bill structure. Recent advances in DNA–DNA hybridisation support this view, and the radical changes in taxonomy brought about by this development include the placing of the Alaudidae in a grouping (the superfamily Passeroidea) that also contains such apparently dissimilar birds as the sunbirds of Africa and Asia, the Old World sparrows, the wagtails, pipits, accentors, finches, buntings, American warblers, New World orioles and the tanagers. Even this placing may, however, be incorrect, and Barker et al. (2002) used evidence from conserved nuclear genes to argue that the larks’ closest living relatives may, in fact, be the cisticola warblers (a largely African family), another group of birds that reach their greatest abundance in open habitats. Cisticola warblers are also cryptically plumaged, although this may represent a common adaptation to living in open environments with few hiding places rather than any close evolutionary relationship. Within the larks, a growing body of evidence suggests that the basal genus might be the strange (and, intriguingly, the most superficially cisticola-like) Heteromirafra larks, whose small and fragmented range might indicate a particularly ancient group (Peter Ryan, pers comm.).

Around 100 species of lark are currently recognised, the exact number depending on whether certain forms are considered as single species or groups of closely related species. Recent studies suggest that several forms that were once thought of as subspecies should now be treated as full species, and the number of generally recognised species is gradually increasing. For example, the long-billed lark co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Colour plates

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 - The larks

- Chapter 2 - Distribution and variation

- Chapter 3 - Populations and habitats

- Chapter 4 - Song and song flight

- Chapter 5 - Mating and territoriality

- Chapter 6 - Nests and eggs

- Chapter 7 - Raising the chicks

- Chapter 8 - Productivity

- Chapter 9 - Migration and other movements

- Chapter 10 - Winter

- Chapter 11 - Survival and mortality

- Chapter 12 - Skylarks and modern agriculture

- Chapter 13 - Poetry, persecution and the rise of popular protest

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Plates

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Skylark by Paul Donald in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.