- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Goshawk

About this book

A large and spectacular bird of prey, the Goshawk lives in boreal forests throughout the Northern hemisphere. The Goshawk is an authoritative yet highly readable monograph of the species.

A powerful hunter of large birds and woodland mammals, it was persecuted for many years by game keepers to the point of extinction in the UK. However, escaped falconry birds led to the establishment of a new population in the 1960s, though the species remains rare and elusive - birders need a combination of hard work and a little luck to see this magnificent raptor.

The Goshawk includes chapters on nomenclature, races and morphs, biometrics, nesting, incubation and chick-rearing, migration, feeding ecology, population dynamics, and conservation, punctuated throughout with illuminating tales from author Robert Kenward's extensive field research. The book is packed with illustrations, figures and maps, and contains a selection of the author's superb photographs of the birds.

The product of almost 30 years work, this title is a classic Poyser monograph; birders will enjoy the fascinating insights into the biology of the bird, while academics will appreciate the book's comprehensive literature review.

A powerful hunter of large birds and woodland mammals, it was persecuted for many years by game keepers to the point of extinction in the UK. However, escaped falconry birds led to the establishment of a new population in the 1960s, though the species remains rare and elusive - birders need a combination of hard work and a little luck to see this magnificent raptor.

The Goshawk includes chapters on nomenclature, races and morphs, biometrics, nesting, incubation and chick-rearing, migration, feeding ecology, population dynamics, and conservation, punctuated throughout with illuminating tales from author Robert Kenward's extensive field research. The book is packed with illustrations, figures and maps, and contains a selection of the author's superb photographs of the birds.

The product of almost 30 years work, this title is a classic Poyser monograph; birders will enjoy the fascinating insights into the biology of the bird, while academics will appreciate the book's comprehensive literature review.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

Names, races and relatives

It is the summer of 1982, in Moscow. The metro is admirable, with other architecture a blend of function and stark grandeur. The display of a mere half-dozen products in neighbourhood food shops is a shock. Vladimir Galushin, a host at the 18th International Ornithological Congress, has kindly arranged for me to visit the museum, where large wooden chests carry magical names: ‘buteoides’, ‘fujiyamae’, ‘schvedowi’, ‘albidus’.

Fascinated by the concept of a white Goshawk, I open the ‘albidus’ box and start laying out birds to photograph (Plate 7). The first bird, with label neatly written in Cyrillic on a flattened and stiffly crossed leg, is the pale colour I had expected, perhaps helped a bit by bleaching in the years since its death. The second bird is pale too.

However, as I work down through the box, taking measurements and scoring plumage characteristics, some of the birds start to look remarkably like the adults and young I’ve known from Fennoscandia. It is the same in other boxes. The birds at the top make fine photographs of what is considered typical for the appropriate race, but those lower down could have come from any of the boxes. Some birds even have dark central streaks on their breast feathers, reminiscent of Goshawks from North America.

Of course, these stiff skins that smell of moth-proofing naptha lack eyes, which also change colour geographically. However, one thing is clear. If there ever were truly distinct races of Goshawk across the Eurasian land-mass, perhaps trapped by ice-ages in isolated pockets, interbreeding has long since softened the distinctions between them. Only the most typical of these morphs, the sort that are provided to museums as outstanding specimens, can be distinguished by physical characteristics alone.

Intrigued, I start measuring wing-lengths and middle toes, and scoring the colours and patterns of breast feathers and backs, in order to seek trends. The helpful museum staff read the place names in Russian. It worries me that the hawks collected in winter may have travelled some distance from their nest sites. Across the 180° of Eurasia this should be a relatively small latitudinal error, but some northern hawks may have been collected far to the south. Ideally one should examine live hawks sampled at nests at regular intervals of longitude and latitude. It is also worrying that some hawks may have been sent to the museum specifically because they were atypical: one hopes that these were few among the 209 skins. After entering the museum with a view of taxonomy as rather mundane, I leave with more appreciation of the fascinating challenges it contains, and make trips in the autumn to measure more museum skins, in Stockholm and Chicago.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Raptors are named from their prey in many languages. In English we have mouse-hawk, duck-hawk, pigeon-hawk, chicken-hawk, sparrow-hawk, for species which made themselves noticeable by what they ate. The Northern Goshawk is a pigeon-hawk in modern Danish (Duvhøk), French (Autour des palombes), Hungarian (Galambasz heja) and Swedish (Duvhök), while the Finnish (Kanahaukka) and Norwegian (Hönsehök) names allude to the theft of chickens. The Germans, in the spirit of re-naming raptors Greifvögel (birds which seize) from the earlier Raubvögel (birds which steal), have dropped an earlier ‘chicken’ prefix and just use the word ‘hawk’ (Habicht), like the Dutch (Havik). The Russian is Yastreb Teterevyatnik, literally ‘black-grouse hawk’. The Slavic word yastreb for hawk may be related to the original Latin generic name Astur, which has connotations of speed, as in strela (Russian for ‘arrow’). The Turkmen name of Garynchykar implies both speed and powerful seizure, while the Ottoman name of Çak ´yrkuþu (chakirkushu) means a greyish-blue bird, although Turkish villagers now often use Tavukkapan, meaning ‘chicken-snatcher’ (O. Borovali, pers. comm.).

In their book Pedigree: Words from Nature, Potter & Sargent (1973) had no doubt that the prefix ‘gos’ is Old English for goose, as in Gosport and gosling. An adaptation of the word ‘gross (groâ)’ for large, as in grosbeak, is also conceivable. The large size of Goshawks is recognised in a German local name Doppelsperber (double sparrow-hawk) and the Turkish Atmaca þahini (greater sparrow-hawk). However, Germans have also used the word Gänsehabicht (goose-hawk) in the past (Fischer 1980). Goshawks seldom take wild or farmyard geese nowadays, but perhaps domestic geese were smaller where Goshawks and Gänsehabichte were named.

In the scientific name, Accipiter is literally hawk and gentilis means ‘belonging to a clan or species’ (Cooper 1981). In the 12th century Latin used by Linné in 1758 to name the species, gentilis also implied ‘of good birth’ (hence the term ‘gentlemen’). The original generic name Astur links to names in Romance languages of Astor in Catalan, Autour in French and Azor in Portuguese and Spanish. The Azores are ‘hawk-islands’, although the hawks there are buzzards.

The Northern Goshawk is one of those few species with a Holarctic distribution, i.e. extending across the Eurasian Palaearctic zone as well as the North American Nearctic. If we travel a third of the circumference of the world to the west from Europe, this species continues to be named with respect and irritation. Thus, the totem pole of St’aawaas Xaaydagaay, the ruling family of the Cumshewa First Nation on Haida Gwaii (in the Queen Charlotte Islands) is topped by a blue hawk with red eyes, which is most likely a Goshawk (F. Doyle, pers. comm.); the bird is known colloquially as a chicken hawk. If we travel a similar distance east, to Manchuria, the name is Cang Ying, meaning ‘a hawk with pale plumage’ (Zhang Zhengwang, pers. comm.). Other Chinese names include Huang Ying, meaning ‘yellow hawk’ (perhaps named from the juvenile) and Ji Ying (gamebird hawk). In Japanese the Goshawk is Ootaka, or ‘blue hawk’.

The names for this species reflect human attitudes. Europeans name the Northern Goshawk from observations of predation, with northerly ‘grouse hawk’ and southern ‘pigeon hawk’ being rather accurate according to Chapter 8, and the older German ‘chicken-hawk’ less sympathetic. Moving east from Slavic to Turkic languages, ideas of speed, strength and colour became prevalent. Names based not on imputation but colour alone are used in the prolonged eastern civilisations of China and Japan, where Goshawks remained esteemed through a long history of falconry (Chapter 9).

PLUMAGE

The plumage of nestling Goshawks has been described by many authors (e.g. Siewert 1933, Bond 1942, Boal 1994a). Newly-hatched hawks have a short coat of snow-white down, grey-black eyes, and legs which turn within a few days from pinkish to pale yellow. The beaks are jet black and relatively smaller in relation to the greenish-yellow cere than at fledging.

The second coat of down, which develops at 7–10 days old, is longer and silkier, with a slight grey tinge on the back. Down always remains shorter and sparser on the chick’s underside. The main tail feathers start at 14–16 days, followed by the contour feathers on the back. By the time the birds fledge, at 35–42 days, the main flight feathers are two-thirds grown, the eyes have faded through slate-grey to blue-grey, and the cere and legs are becoming darker yellow. Feather growth is complete two weeks after leaving the nest.

There is considerable variation in the juvenile first-year plumage. Northern European birds, ascribed to the nominate race A. g. gentilis, have chocolate-brown to mid-tan crowns, body and upper wing surfaces, the feathers being edged with a paler shade which sometimes contrasts sufficiently to give a gentle speckling. The underparts have a lighter base colour (Plates 3, 5 & 7), which varies from pale cream (var. fulviana) through buff to a pale rusty colour (var. rufina). These may be distinct phenotypes, because young occasionally show very different colours in the same nest. Among museum specimens, the darker type was more common in skins from central Siberia and China, but uncommon again in the far east of Siberia and was not attributed to North American skins (Figure 1).

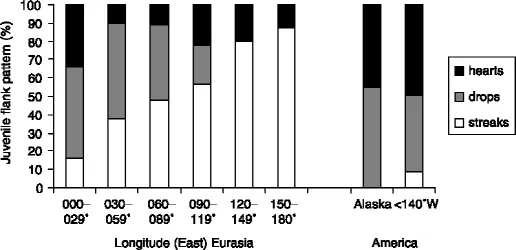

Most ventral feathers also have a chestnut to deep-chocolate central marking along the shaft, although the undertail feathers tend to be unmarked. This marking may be a relatively narrow streak of fairly constant width, or may vary along its length for up to half the width of the feather, or become a broader, often heart-shaped character (Figure 2). The heart-shaped markings are usual under the wings, and often to be seen on the flanks, while on some birds they are also noticeable on the breast (var. cordata). The juveniles that remain streaked (var. striata), have these contrast-rich markings widest and most prominent on the chest, and finer on throat and flanks (Fischer 1980). Streaked juveniles become more frequent to the east of Eurasia, but are rare in North America (Figure 3).

The pale ventral colouration is also noticeable on the eyebrows (Plate 5), although the superciliary stripe is by no means as striking as in adult hawks (Plates 1 & 4), and towards the base of the nape feathers. These nape feathers are quite white at the base, another feature which is more prominent in adult hawks and probably has a signalling function (Brüll 1964).

As in most other accipiters, the seventh of the ten primaries (fourth from the front) is normally the longest. The 12 main tail feathers (very rarely 13 or 14, Slijper 1978) have distinct dark-brown to black transverse bands, which are as wide as the paler base colour and more clearly fringed with white in some hawks than in others. There are typically five bands on the central tail feathers, six or seven on the outermost pair. The dark terminal band has an especially broad white fringe at its outer end, providing a pale tip to the tail which stands out in nestlings and first-autumn hawks, but can wear down later in the first year. The black beak and claws of nestlings become more blue-black after the birds have fledged, while the cere and legs become darker yellow. The claws on the rear and inner front toes are much larger than the others, for delivering the formidable killing grip, while the other toes are finer and usually have better developed ventral pads. The eyes have become pale yellow within a month or two of fledging (Plate 5), sometimes even before hawks leave the nest.

Figure 1. Breast colour of 161 juvenile Goshawks in musem collections.

Figure 2. Breast feathers, showing (left to right) juvenile streaks, juvenile hearts and adult bars typical for Europe and North America. Relatively pale bars on American adults make shaft streaks especially prominent on the breasts (Plates 7 & 13).

The plumage of adult and first-year Goshawks is so different that Linné considered them two species, Falco (=Astur, =Accipiter) gentilis for the young hawks and Falco palumbarius for the adults. At the first moult, when the hawks are a year old, the upper parts change from brown to a dark grey, typically with a slightly brownish tinge in second-year birds but becoming grey in subsequent moults, in shades ranging from black to an attractive blue-grey. The crown and sides of the head usually become darker than the back in later moults, and may be completely black. Contrast between back and head is enhanced by the white inner parts on the nape feathers, which give a slightly speckled impression with the feathers flat, and are very conspicuous when the feathers are raised at the back of the crown by an aggressive hawk. The superciliary stripe on each eyebrow becomes most conspicuous after the second moult, the white being flecked with black on some of the tiny feather shafts (Plate 4). Adults’ back colours were palest for museum hawks from central Eurasia and North America (Figure 4).

The main tail and wing feathers are greyer in adults than juveniles, but retain much of the first-year markings at least in the second year. The bands usually become less distinct in later moults (Brüll 1964).The detailed pattern of these feathers is consistent enough between moults for the recognition of individual hawks at nest sites (Kollinger 1964, Opdam & Müskens 1976, Ziesemer 1983, Rust & Kechele 1996, see Chapter 5). The snow-white undertail coverts are particularly striking when spread during courtship (Plate 12).

Figure 3. Pattern on flank feathers of juvenile Goshawks in museum collections.

The rest of the underparts are barred black on white (Plates 1 & 2), although the feathers often have a brownish ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Prologue

- Foreword

- Chapter 1 - Names, races and relatives

- Chapter 2 - Weights and measures

- Chapter 3 - Nesting and laying

- Chapter 4 - Incubation and rearing

- Chapter 5 - Markers and movements

- Chapter 6 - Diet and foraging

- Chapter 7 - Prey selection and predation pressures

- Chapter 8 - Death and demography

- Chapter 9 - Falconry and management methods

- Chapter 10 - Conservation through protection and use

- Appendices

- References

- Plates

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Goshawk by Robert Kenward in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.