- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Great Auk Islands; a field biologist in the Arctic

About this book

The story of the author's research expeditions in the Canadian Arctic, this book is for professional and amateur ornithologists, students in ecology and animal behaviour.

The Arctic is one of the world's last great wildernesses: a place of outstanding beauty, history and extraordinary wildlife in which seabirds form an important component of a rich, marine environment. Like many other remote regions, it is under threat from human activities, but to protect it we need to understand it.

That understanding can come only through scientific research and the central threat of this book is to examine how such research is actually done. It describes the business of conducting biological studies on seabirds in remote parts of eastern Canada. Several themes are engagingly interwoven: the sheer beauty of the Arctic environment, the intriguing biology of its wildlife, and the discovery and exploitation of enormous seabird colonies, including the destruction of the Great Auk.

Tim Birkhead describes in personal detail the different facets of research and brings to life both the difficulties and the excitement of working in the Arctic. What is it like setting up a camp for four months on a remote and uninhabited island not far from the North Pole? How does it feel to commute daily by inflatable boat amidst icebergs to study-areas located on towering cliffs, set between ice-blue glaciers? What do you do when a Polar bear decides that you have invaded its Arctic home? Why are the seabird colonies in the high Arctic so enormous? What do we know about lifestyle of the extinct Great Auk? In 1992 Canada's legendary cod fishery was finally destroyed - what are the consequences of this for other wildlife?

These are just a few of the questions dealt with in this book. Our future as a species depends upon science and the understanding it brings of the world we live in. The work of scientists often appears obscure, but in this book, Tim Birkhead has used his experience of seven summers in the Arctic to write an accessible and straightforward account of how research is actually done in the field.

The text is enriched by David Quinn's illustrations, and by numerous photographs in both black and white, and colour.

The Arctic is one of the world's last great wildernesses: a place of outstanding beauty, history and extraordinary wildlife in which seabirds form an important component of a rich, marine environment. Like many other remote regions, it is under threat from human activities, but to protect it we need to understand it.

That understanding can come only through scientific research and the central threat of this book is to examine how such research is actually done. It describes the business of conducting biological studies on seabirds in remote parts of eastern Canada. Several themes are engagingly interwoven: the sheer beauty of the Arctic environment, the intriguing biology of its wildlife, and the discovery and exploitation of enormous seabird colonies, including the destruction of the Great Auk.

Tim Birkhead describes in personal detail the different facets of research and brings to life both the difficulties and the excitement of working in the Arctic. What is it like setting up a camp for four months on a remote and uninhabited island not far from the North Pole? How does it feel to commute daily by inflatable boat amidst icebergs to study-areas located on towering cliffs, set between ice-blue glaciers? What do you do when a Polar bear decides that you have invaded its Arctic home? Why are the seabird colonies in the high Arctic so enormous? What do we know about lifestyle of the extinct Great Auk? In 1992 Canada's legendary cod fishery was finally destroyed - what are the consequences of this for other wildlife?

These are just a few of the questions dealt with in this book. Our future as a species depends upon science and the understanding it brings of the world we live in. The work of scientists often appears obscure, but in this book, Tim Birkhead has used his experience of seven summers in the Arctic to write an accessible and straightforward account of how research is actually done in the field.

The text is enriched by David Quinn's illustrations, and by numerous photographs in both black and white, and colour.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Great Auk Islands; a field biologist in the Arctic by Tim Birkhead in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Science & Technology Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Horizon Opening

Nothing in the whole system makes sense until the natural history of the constituent species becomes known. The study of every kind of organism matters, everywhere in the world.

Wilson (1987)

As the men I have named clambered up they saw two Gare-fowls [Great Auks] sitting among numberless other rock-birds (Uria troile and Alca torda), [Common Guillemots and Razorbills], and at once gave chase. The Gare-fowls showed not the slightest disposition to repel the invaders, but immediately ran along under the high cliff, their heads erect, their little wings somewhat extended. They uttered no cry of alarm, and moved, with their short steps, about as quickly as a man could walk. Jon with outstretched arms, drove one into a corner, where he soon had it fast. Sigurdr and Ketil pursued the second, and the former seized it close to the edge of the rock, here risen to a precipice some fathoms high, the water being directly below it. Ketil then returned to the sloping shelf whence the birds had started, and saw an egg lying on the larva slab, which he knew to be a Gare-fowl’s. He took it up, but finding it was broken, he put it down again. Whether there was not another egg is uncertain. All this took place in much less time than it takes to tell it. They hurried down again, for the wind was rising. The birds were strangled and cast into the boat. . .

So reads Alfred Newton’s (1861) account of that fateful day in early June 1844 on the island of Eldey, off southwest Iceland, when the last Great Auks were seen alive. The corpses of these two birds were sold to a dealer. The whereabouts of their skins is unknown, but (remarkably) some of their internal organs were preserved and are now in the Museum of Zoology at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

The Great Auk is a symbol: a symbol of man’s greed, short-sightedness and, in the archaic sense of the word, awful ability to ignore apocalyptic warnings. The Great Auk is also a symbol of lost scientific opportunities. How much more we would have known about life, and about marine birds in particular, had the Great Auk still been extant.

How, you might ask, could the study of living Great Auks tell us more about life? The answer to that question forms part of this book, but we can also answer it in another way. For non-scientists the research done so enthusiastically by scientists must often appear desperately specialized, and it must sometimes also seem trivial. But trying to figure out what scientists do is rather like watching ants (Thomas 1974). If you sit down beside a large colony of wood ants and focus closely on just one individual you might see it dragging a pine needle, stumbling over twigs, and falling into minor crevasses. As far as you can see it appears to be moving around in an uncoordinated fashion. However, if you put the magnifying glass away and step back to look at the large and complex nest which the colony has constructed, then you begin to realize that all that seemingly random, individual effort is not for nothing. Although the contribution of each ant appears trivial, the combined effort of the entire colony produces something substantial, tangible and impressive. In just the same way many modest contributions add to the store of human knowledge, a process which ‘has been the secret of Western science since the seventeenth century, for it achieves a corporate, collective power that is far greater than any one individual can exert’ (Ziman 1969).

Few books are written about how scientists work. Scientists are often seen as a different breed from the rest of humanity and what they do often appears to be unintelligible to the lay-person. The public’s image of scientists is made worse by the media who often portray them, at best as cold, calculating and perfectly objective, interested only in ‘their’ problem, and at worst as eccentric. Of course, some scientists are all of these, but a great many are not. Because scientists are forced to tell the world about their findings through the unexciting channels of the scientific literature, it is hardly surprising that their work often appears terse and dull. ‘To the non-scientific outsider the prose style of the standard scientific paper gives the impression that the paper has in some curious way not been written by a human being’ (Charlesworth et al. 1989). But there is no need for scientists to write in a boring or esoteric way. I have always felt that even relatively complicated biological ideas can be explained simply and I tell my students to write their PhD theses and research papers so that their parents can understand them (on the basis that most of them arise from non-scientifically trained stock). Unfortunately, even if scientists adopt this type of approach, the way in which they go about their business can still be difficult to appreciate, no doubt partly due to the shortage of space in scientific journals and the telegraphic style of writing we are forced to adopt.

Although many would not admit it, I believe that scientists often dislike their own style of writing. A habit I have noticed among my colleagues is that even if they do not read a scientific paper from beginning to end, almost all of them read the ‘acknowledgements’. This is the short section at the end of a paper where the author (or authors) can thank the various people that have helped them in different ways with their study. Why are these acknowledgements so fascinating? I think the answer lies in the fact that this is often the only opportunity for scientists to try to inject a glimmer of humour or humanity into their writing. The acknowledgements section is thus the only ‘window’ the reader has through which to try and catch a glimpse of the author as a real person.

Science has been described as 5% inspiration and 95% percent perspiration. While this is largely true, it belies the effort involved in coming up with an original idea in the first place, but there is no doubt that testing ideas can entail a lot of hard and repetitive work. Long hours of field work, often carried out under dangerous, boring or exciting conditions, are usually summarized in a few dull sentences, in the name of objectivity. At an early stage in my career I read a paper in the journal Animal Behaviour on the social behaviour of orangutans. In contrast to most other papers I had read, this one described in more than usual detail the potential problems of working in the Sumatran rainforest, including tangles with snakes and other predators. This brought the paper alive for me, and I read on. . .

In this book I want to try to do something similar and thus to overcome some of the inaccessibility of science. In so doing I will describe, as a field biologist, the logistics, the peripheral benefits (such as the location itself and the other wildlife), and the thought processes involved in doing science. I will also try to convey something about both the excitement and the frustration of conducting research.

A close friend once told me, with the slightest hint of envy, that I live a charmed life, and in the sense that my work is also my hobby, this is probably true. I have been fortunate in knowing since I was very small exactly what I wanted to do. For as long as I can remember I have enjoyed watching what birds and other animals do, and many of my colleagues who are professional field biologists were also naturalists when they were young. But what causes naturalists to metamorphose into scientists? Like others interested in natural history, those that are content to remain as birdwatchers are happy simply to record or describe the organisms they see. The scientist, however, wants something more. Through a powerful creative urge they want to generalize, to pull together and synthesize lots of facts and to come up with broad explanations for the patterns they encounter in nature. However, precisely what it is that makes some of us want to pull things together’, has so far eluded those that study these things. In fact, while there have been attempts to analyse the temperament of scientists who study physics and chemistry (McClelland 1962), I can find no equivalent investigations of biologists. For what it’s worth, a study of (male) physicists found that they apparently tend to be loners as children, are ‘typically not very interested in girls, marry the first girl they date and thereafter show a rather low level of heterosexual drive’. While it is certainly true that some biologists tend to have solitary childhoods, as for the rest . . . I doubt it.

A multitude of factors determine our future course of development, but some incidents can be particularly potent in shaping our lives. I can vividly recall being taken as part of a family holiday at the age of 11 to Bardsey Island, off the Llyn Peninsula in North Wales. Everything about the place was exquisite: the islandscape, the seabirds, the wheeling flocks of Choughs, and the numerous grey seals. On our walk around the island, we saw someone sitting near the cliff edge with binoculars intently watching some birds and writing down what they saw in a field notebook. As I scrutinized them through my own binoculars, my father suggested to me that I could do something like that in the future, and the seed was sown.

Much later, as a zoology undergraduate my main interests were, not surprisingly, in the behaviour and ecology of animals in the wild. My thoughts became focused during one particular lecture, given by Robin Baker, which described some of Geoff Parker’s work on the evolutionary aspects of dungfly courtship and mating behaviour. Parker’s study appealed to me because it involved asking very specific questions, couched within a framework of evolutionary ideas. ‘Why do male dungflies remain coupled to females after they have finished mating?’ I knew from that day that this was the type of biology I wanted to do. Dungflies are not especially charismatic and do not sound very promising as sources of inspiration, but it was not the animals themselves that mattered, but the subject and the way the study was conducted that fired my imagination.

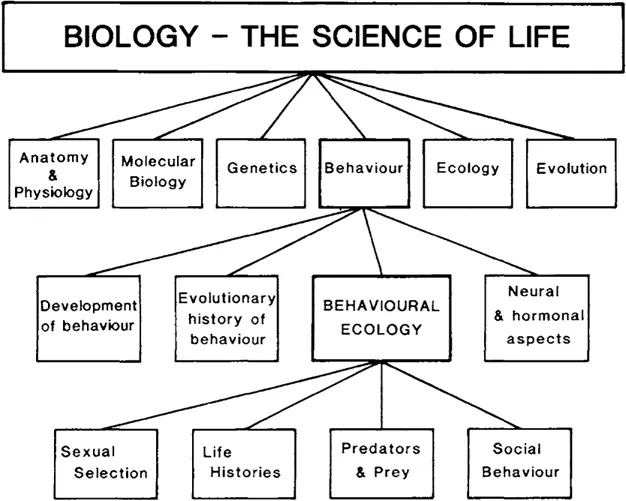

Many of the ideas described in that course of lectures subsequently developed into the discipline now called behavioural ecology. Parker’s approach was to test ideas using a common and easily observed organism, which happened to be Scatophaga stercoraria, the yellow dungfly. We were privileged as undergraduates to be told about these ideas a year or so before they were published and became sucked into the mainstream of behavioural biology. Behavioural ecology is basically natural history conducted within a robust framework of evolutionary principles (Wilson 1975; Dawkins 1976; Krebs and Davies 1978). Where it fits into the ants’ nest of science is shown in Fig. 1. The essence of the behavioural ecology approach is that behaviours, or structures associated with behaviours such as the antlers of deer or the gaudy plumes of birds of paradise, are weighed for their adaptive significance. That is, behavioural ecologists, on seeing an animal with an elaborate structure, or performing a particular behaviour, ask themselves: ‘how does this behaviour increase that individual’s chances of reproducing or surviving?’.

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram showing the relationship between biology, behaviour, behavioural ecology and some of the different components of the study of behavioural ecology. This figure is not meant to be comprehensive; its aim is simply to illustrate the way ants working on one part of a structure can contribute to the whole.

Much of Parker’s research on dungflies centred on their mating behaviour—after all, this is the way that genes are transferred, but I was intrigued to learn that all was not as it appeared. A male dungfly may successfully copulate with a female but still fail to fertilize her eggs. Such reproductive failure can arise from cuckoldry—because another male mates with the same female, displacing the original male’s sperm and replacing it with his own! And the reason why males remain attached to females after mating is to deter other males from mating with ‘their’ female. It is this element of the unexpected that makes behavioural ecology so exciting. Parker referred to the competition between the sperm from different males to fertilize a female’s eggs as ‘sperm competition’ and I wondered if anything similar might occur in birds This question became the major focus of my research over the next 20 years, but as we shall see, by a circuitous, polar route.

In the early 1970s PhD projects for postgraduate students were still very much orientated towards species, rather than being concerned with more general problems, as they are now. My PhD was on Common Guillemots on Skomer Island, off the south Wales coast, and the main reason for conducting this study was that the number of Common Guillemots in Britain had declined dramatically during the previous 40 or 50 years. My remit was to try and find out the cause of the decline. However, there was sufficient scope within the study to try to apply some of Parker’s ideas, albeit in a very limited way. The opportunity was limited because the behavioural ecology approach centres on what individuals do and I therefore needed to be able to recognize individual birds, which was not possible, at least not on the scale I required to make sense of their promiscuous mating relationships. My efforts were also limited for another reason. The hardest part of any study comes in deciding exactly which questions one wants to ask, and at that stage I was still very uncertain about just what were the right questions to ask about sperm competition in birds. Once that initial barrier is overcome, however, the rest is relatively easy. Doing science is rather like being dumped on the moors and told to find your way home: difficult, until you are given a compass and a bearing.

Bardsey was my first island experience: a haven for wildlife, but also the final resting place for large numbers of medieval holy men or ‘saints’. Their abundant remains are now occasionally unearthed by the elements and the plough. Like several other islands around the coast of the British Isles, Bardsey held a special place in the hearts and minds of saints, who chose to rest their earthly bodies there. Presumably, by being buried somewhere as beautiful as Bardsey they felt as though they were already on their way to heaven.

For both scientific and other reasons islands have always attracted biologists, such as Charles Darwin, Frank Fraser Darling, Ronald Lockley and others. Scientifically, islands offer the biologist a number of special advantages, one of the most important of which is the finite nature of the animal or plant populations they contain. The island itself sets the limit for the extent of the population; because of the surrounding sea the population cannot extend beyond the island’s physical limits. Another feature of islands that attracts biologists is the occurrence, on some islands at least, of unique forms of mainland species. St. Helena in the South Atlantic, for example, boasts the biggest earwig in the world, some 8 cm long! Skomer Island has its own vole, a larger, redder and tamer version of the mainland bank vole, with an unusual tooth (bearing an extra cusp). These special island forms evolve to be different from their mainland relatives for a number of different reasons, but partly because the ecological conditions on islands differ from those elsewhere. The tameness of the Skomer Vole, for example, is at first sight extraordinary: if you catch one and place it in the palm of your hand, it will simply remain there. Try that with a mainland bank vole and you will end up with bloody fingers and the blurred image of a rapidly disappearing s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 - Horizon Opening

- Chapter 2 - Margins of the universe

- Chapter 3 - Nameless days

- Chapter 4 - The Lives of Great Auks

- Chapter 5 - Labrador

- Chapter 6 - Skouts, Skuttocks and Strangers

- Chapter 7 - Between species in Labrador

- Chapter 8 - The Fertile Sea

- Chapter 9 - Changes

- Appendix 1 - List of common and systematic names

- Appendix 2 - Notes on the local seabird names used in Labrador

- References

- Colour plates