- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Watching Birds

About this book

This revised edition of the late James Fisher's much praised Watching Birds is the work of Dr Jim Flegg, Director of the British Trust for Ornithology.

In his Preface Dr Flegg writes: 'It is a daunting task to revise the bird book on which you cut your teeth: it is the surest measure of the man who wrote it that what is needed, after thirty-odd years, is an updating and not a sweeping revision.'

Among James Fisher's deservedly popular writings Watching Birds was probably the most read and consulted. After several reprints (published by Penguin Books) he planned to re-write it, and it is wholly appropriate that the work should now be done by Dr Flegg who, like the original author, has done much to help arouse and stimulate a widening interest in watching and understanding the life and world of birds.

It is an indication of that interest today that radio and TV programmes (in which Dr Flegg has frequently participated) have audiences of millions. Such numbers are hardly surprising since few leisure activities offer as effective or as gratifying an antidote to the pressures of modern life as birdwatching - and few can be as readily and inexpensively pursued at almost any time, anywhere.

Watching Birds has been an introduction and an item of basic equipment to tens of thousands of birdwatchers in the past, and this new and revised edition is assured of an even wider audience.

Jacket colour photograph by Jim Flegg.

In his Preface Dr Flegg writes: 'It is a daunting task to revise the bird book on which you cut your teeth: it is the surest measure of the man who wrote it that what is needed, after thirty-odd years, is an updating and not a sweeping revision.'

Among James Fisher's deservedly popular writings Watching Birds was probably the most read and consulted. After several reprints (published by Penguin Books) he planned to re-write it, and it is wholly appropriate that the work should now be done by Dr Flegg who, like the original author, has done much to help arouse and stimulate a widening interest in watching and understanding the life and world of birds.

It is an indication of that interest today that radio and TV programmes (in which Dr Flegg has frequently participated) have audiences of millions. Such numbers are hardly surprising since few leisure activities offer as effective or as gratifying an antidote to the pressures of modern life as birdwatching - and few can be as readily and inexpensively pursued at almost any time, anywhere.

Watching Birds has been an introduction and an item of basic equipment to tens of thousands of birdwatchers in the past, and this new and revised edition is assured of an even wider audience.

Jacket colour photograph by Jim Flegg.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introducing the birdwatcher

to the bird

“My remarks are, I trust, true in the whole, though I do not pretend to say that they are perfectly void of mistake, or that a more nice observer might not make many additions, since subjects of this kind are inexhaustible.”

GILBERT WHITE, 9 December 1773

THE BIRDWATCHER

Though they are by no means the most ubiquitous, numerous, curious, or diversified forms of life, it is nevertheless a fact that birds have had more attention paid to them than any other corresponding group of animals. Many attempts have been made to discover why so many people like birds, but nobody has so far given a really satisfactory answer. When it comes, it will probably be found partly from a sort of mass observation and partly from the long and detailed history which birdwatching has enjoyed, particularly in Britain. Certainly birds are relatively obvious and always about us, but they are extremely mobile in contrast with other beautiful and interesting natural things like flowers.

All sorts of different people seem to watch birds: James Fisher knew of a Prime Minister, a Secretary of State, a charwoman, two policemen, two kings, one ex-king, five Communists, four Labour, one Liberal, and three Conservative Members of Parliament, the chairman of a County Council, several farm-labourers, a rich man who earns two or three times their weekly wage in every hour of the day, at least forty-six schoolmasters, and an engine-driver. To these can be added today (in reflection of both political and cultural shifts of emphasis) two Princes Consort, at least two Presidents, numerous peers, a Field Marshal and many people falling under the general heading of ‘show business personalities’. The number of birdwatchers is now impossible to estimate—our only guide to its enormity is the membership of the various formal clubs and societies, some local, some national, which must now be approaching the half-million mark. Obviously, these are only a small fraction of those with a genuine interest in, and feeling for, birds.

The reasons which make these men and women interested in birds are, surely, very divergent. Some, when asked, can give no particular reason for their liking for birds. Others are quite definite—they like their shape, their colours, their songs, the places where they live; their view is the aesthetic one. Many of these paint birds or write prose or poetry about them. Still others, like several of the schoolmasters, are grimly scientific about them, and will talk for hours on the territory theory, the classification of the swallows, or changes in the bird population of British woodland during historic times. The luckiest ones are those who blend the two: retaining the aesthetic pleasure and adding to it the delights realised by an inquisitive interest.

The observation of birds may be a superstition, a tradition, an art, a science, a pleasure, a hobby, or a bore; this depends entirely on the nature of the observer. Those who read this book may give bird watching any one of these definitions; which is a sound reason why we should get down as soon as possible to the business of introducing the bird-watchers to the birds.

THE BIRD

Birds are animals which branched off from reptiles at roughly the same time in evolutionary history as did the mammals. Though both birds and mammals have warm blood, from anatomical considerations it is clear that these two branches are quite separate, and that the birds of to-day are more closely related to reptiles than they are to mammals. The parts of the world that birds live in are rather limited. Though birds have been seen in practically every area of the world from Pole to Pole and at heights more than that of Mount Everest, yet they have rarely been found to penetrate more than about 30 feet into the earth or about 150 feet below the surface of the sea; and every year some part of their lives has to be spent in contact with land, for birds cannot build nests at sea, even though some freshwater species build floating nests and rarely step onto dry land.

In the hundred and thirty million years or so in which birds have existed as a separate class of animals, they have retained their basic structure to a remarkable extent, and, compared with the situation in other classes of animals, even the apparently most widely distinct birds are internally little different. To avoid going into anatomical details, it must be enough to say that the same bones (that is, homologous ones) exist in the wings of humming-birds and ostriches, and in the feet of hawks and ducks. What has happened in the course of evolution is that these have been modified for different purposes. The wing of the humming-bird has become perhaps the most efficient organ of flight in the animal kingdom; (the humming-bird is, as far as we know, one of the few birds which can actually fly backwards); while that of the ostrich, which can no longer fly, is used as an organ of balance and of display, The talons of the hawk, provided as they are with terrible claws, grasp its prey, and are usually the weapons which cause the victim’s death (rather than the beak); while the feet of the duck are webbed so that it can walk upon mud and swim. Figure 1 gives just some idea of the immense variety of foot adaptation and Figure 2 shows some of the adaptations of beaks to feeding.

1 Birds’ feet adapted to differing modes of life: (a) finch family (passerine birds)—perching; (b) woodpecker—tree climbing; (c) Sparrowhawky—seizing prey in flight; (d) Water Rail—load-spreading; (e) Puffin—(three-toed) swimming; (f) Coot—(lobed) swimming and load-spreading; (g) Shag—(four-toed) swimming; (h) Barn Owl—gripping prey

Many are the ways in which birds are adapted to their surroundings, and to the lives which nature (or, if you like, evolutionary history) has taught them to live. Many interesting adaptations can be seen in British birds: so that they may climb trees and cling to them while hunting insects, the woodpeckers have feet with two toes pointing forwards and two aft, and the under-side of their tail feathers is rough where these rest against the trunk of the tree as the birds climb; their beaks are like chisels, for often they carve much of their nest out of the living wood, and their food habits take the great beaks under bark and into crevices in their search for insects. The central tail feathers of woodpeckers are specially strengthened to serve as a prop while the bird feeds, but those of the Nuthatch, a bird of very similar habits, are not. The Nuthatch, however, unlike the woodpeckers, can climb both head-up and head-down because it is not dependant on support from its tail. In North America one group of woodpeckers has gone even farther, not so much in adaptation as in the habits produced by such an adaptation. They have deserted insect catching for sucking the sap of the trees—hence their name of sap-suckers—and this is a warning to the unwary: birds are not always what they seem, and adaptations may hide relationships, or indicate false ones.

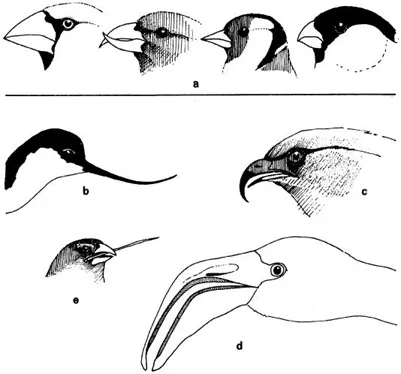

2 Birds’ beaks adapted to special feeding methods: (a) Hawfinch, Crossbill, Goldfinch and Bullfinch—seed crushing and extraction; (b) Avocet—skimming for small molluscs, crustacea, etc; (c) Everglade Kite—(snail eating) shell piercing and extraction; (d) flamingo—filtering plankton, etc; (e) Galapagos Woodpecker Finch—tool holding (stick to “winkle” insects from holes)

Many birds are beautifully adapted to their surroundings at the earliest stage of their lives: the egg. The eggs of the Ringed Plover and of other shore birds often resemble very closely the pebbles among which they are laid (Plate 14); those of birds which build open nests are often coloured with a protective pattern of pigment. But it is a biological economy to lay an egg without pigment where pigment is unnecessary. The eggs of woodpeckers and owls are white when they are laid, and coloured later on only by dirt, and these birds nest in holes where their eggs cannot be seen by enemies. Oddly enough, the egg of the Puffin still has grey or red spots, like faint copies of those of its cousin, the Guillemot, which rather suggests that the Puffin has only recently (in the evolutionary sense) taken to nesting in burrows. One of the nicest adaptations of all is shown by the Guillemot, an auk which nests on very narrow cliff ledges. The egg of the Guillemot is conical—almost pear-shaped—and if knocked, rolls in a tight circle on its narrow end, thus staying on the ledge when an egg of normal shape would surely have rolled off.

When we speak of adaptation of the sort which we have just described, we must remember that our attention is likely to be drawn to the more remarkable examples of adaptation to special needs and away from the fact that practically every organ and part of an animal is adapted (directly or indirectly, efficiently or inefficiently, in greater or lesser degree) to the animal’s surroundings, or to its demand at some period of its total or daily life. A bird is what it is partly because of the immediate environment—since food or weather may affect its colour or size—partly because of heredity—which provides machinery, producing in turn variations on which natural selection can act—partly because of chance—since chance appearance of such new variations as are ignored by natural selection may determine some of the characters of an individual or even of an isolated group of individuals. We must remember that not only special kinds of beaks but beaks in general are adaptations. A wing is an adaptation for flying. An egg is an adaptation for nourishing the young. Adaptations, in birds as in other animals, must be regarded in terms of the perspective of the ages, the dynamics of evolution, and the complicated mechanism of heredity. We may regard any characteristic as adaptive if it can be explained as fitting the bird to its mode of life.

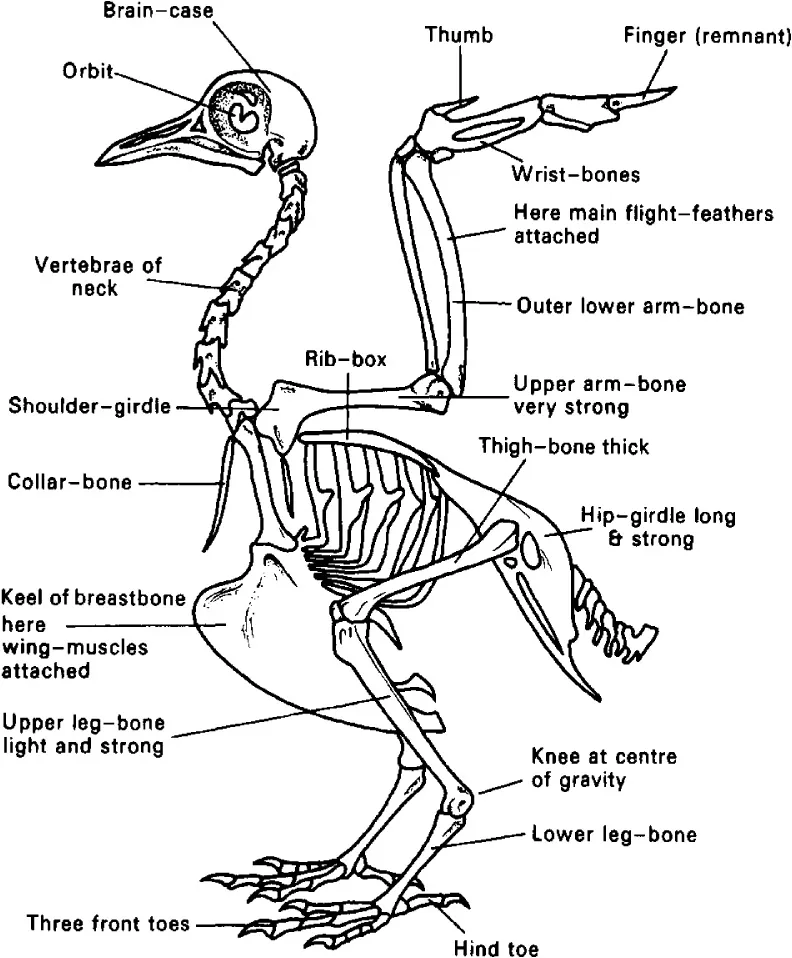

HOW A BIRD IS BUILT

The skeleton of a bird (Fig. 3) is, in general plan, the same as that of other vertebrate animals. Essentially, it consists of a strong box made up of many bony elements, with a variety of attachments. The head, first, is attached to a column of strong articulating vertebrae, the backbone. To the axis provided by the head and vertebrae are attached various appendages; to the head the jaws; to the lower vertebrae of the neck from one to four “floating” ribs; to the vertebrae of the back, ribs which curve forwards to join the huge breast-bone, forming the strong case inside which the lungs and heart lie, and to the outside of which is attached, towards the back, the shoulder girdle; to the remaining vertebrae the hip girdle. The shoulder girdle supports the elements of the wings, the hip girdle those of the legs.

The number of vertebrae in birds is most variable, unlike that in mammals. A swan may have twenty-five bones in its neck, a sparrow only sixteen. (It is odd to recollect that a giraffe, in common with man, has only seven.) In the region of the back some pigeons may have only three vertebrae whose ribs meet the breast-bone, while ducks, swans, gulls, rails or auks may have seven or eight. In the last group the thorax (the box formed by ribs and breast-bone) is very long, and the un-protected abdominal region between it and the base of the tail is very short—a useful adaptation towards a swimming or deep-diving life.

3 Bird skeleton with wings raised—common names given

One of the chief characteristics of a bird’s bones that we should expect to find is that of lightness, an adaptation towards flying. Though birds may have large bones, these have not a massive structure. Most are hollow—some have huge cavities which may contain extensions of the air-sacs of the lung—and only occasionally do we find cross-struts (as in the albatrosses). These bones owe their strength and rigidity to a structure so sophisticated as to be emulated by engineers in modern girder design. They are almost unbelievably lighter than a mammal bone of the same size.

Though there are many characteristics of a bird’s skull which show its evolutionary affinities rather than the tasks to which it is adapted, yet it is better for us, in this short review, to consider it from an adaptive point of view. There are several requirements which a bird’s skull must fulfil. First, it must be light; secondly, the loss of teeth and manipulating fore-limbs during the course of evolution must be compensated; thirdly, the brain and eyes must be accommodated and protected. The first point is covered by the fact that few skull-bones of birds are more than plates and struts; the second by the high development of the horny beak, which has to act almost as a limb, and is, in practice, a very effective one; the third by the huge orbits, which leave only a very thin partition between the eyes on each side. These restrict the rest of the brain to the back of the skull—which is accordingly broad. That part of the brain which deals with smell (of which birds have very little sense) is much reduced; that which deals with co-ordination of movement and balance is understandably large; that which deals with what are sometimes called the “higher functions” (such as logic, or aesthetic appreciation, in humans) is small. Nonetheless, some of these “birdbrains” (so wrongly called) are capable of navigating in most weathers, with really pinpoint accuracy, to a wintering place in Africa, and in the case of the Swallow, back here to the very same barn or garage to nest in the succeeding summer.

The greatest differences between the skeletons of birds and those of other vertebrates are found in the skull and in the pectoral girdle and forelimb. The latter corresponds to the shoulder-blade, collar-bone, arm, forearm, and hand of man. The pectoral girdle is attached to the bones of the main trunk at only one point, where the front end of the shoulder-blade is attached, on each side, firmly to the fore-part of the breast-bone. The two shoulder-blades are braced together across the front by the collar-bones, which are fused in the middle to form what we call the wish-bone. Behind, the free ends of the shoulder-blades are bound by stiff and strong ligaments to the ribs and to the vertebrae of the back.

When the wing is working the strain comes directly on to the box formed by vertebrae, ribs, and breast-bone which are together called the thorax. This box has therefore to be extremely strong. It is. At the back the vertebrae are fused together, at the sides the ribs (often with strengthening bony processes) are bound to each other by further ligaments, and in front the breast-bone is built on engineering principles that combine strength with great lightness plus a keel for the attachment of the powerful muscles of the wing.

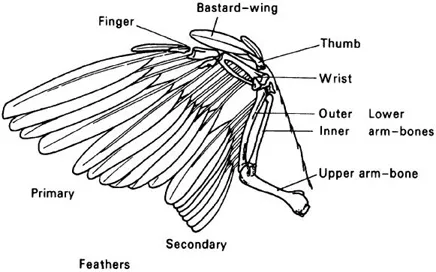

4 Skeletal wing from below

This is the basis upon which the wing can operate. The part that flaps (Fig. 4) is composed of three units. Attached to the shoulder-blade by a ball-and-socket joint is the upper arm-bone (humerus), a single strong rod. To the other end of the humerus are joined the two bones (radius and ulna) of the forearm, and to them in turn is joined the third unit, several small bones, largely fused together (carpals and metacarpals), representing the mammalian wrist and hand.

The muscular force which works the wing is derived almost entirely from huge wedges of muscle attached from the wish-bone in front to the base of the breast-bone below and the shoulder-blade behind. The fibres of these great muscles converge to an insertion on the humerus. By far the larger part of these pectoral flight muscles is concerned with the downbeat of the wing: inside these, connected to the humerus by a complex but subtle tendon system, are t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright page

- Contents

- List of plates

- From the Preface to the 1940 edition

- Preface to 1974 edition

- Note on the illustrations

- Chapter 1 - Introducing the birdwatcher to the bird

- Chapter 2 - Arranging the birds

- Chapter 3 - The tools of birdwatching

- Chapter 4 - Migration

- Chapter 5 - Where birds live

- Chapter 6 - The numbers of birds

- Chapter 7 - Disappearance and defiance

- Chapter 8 - How birds recognise one another

- Chapter 9 - Territory, courtship and the breeding cycle

- Chapter 10 - What you can do

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Watching Birds by James Fisher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.