- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Barn Owl

About this book

In the classic monograph mould, this study of Tyto alba is the product of almost 40 years field work by its authors and complementary observations by other dedicated ornithologists in Britain, the USA and Europe.

The result is a detailed, balanced account based on intimate knowledge of the Barn Owl in varying habitats in Britain, comparing, as appropriate, this race's behaviour with that of sub-species in other areas of the world.

There are major chapters on breeding and general behaviour, feeding, distribution, etc, but voice is rightly given a full treatment.

The text is graced by Ian Willis's fine drawings and there are 31 photographs plus a colour frontispiece.

The result is a detailed, balanced account based on intimate knowledge of the Barn Owl in varying habitats in Britain, comparing, as appropriate, this race's behaviour with that of sub-species in other areas of the world.

There are major chapters on breeding and general behaviour, feeding, distribution, etc, but voice is rightly given a full treatment.

The text is graced by Ian Willis's fine drawings and there are 31 photographs plus a colour frontispiece.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 5

Breeding

The problems inherent in the study of a shy and mainly nocturnal species such as the Barn Owl are daunting to say the least, and we have often had cause to question our sanity in attempting such a task. For one thing the number of useful observations one is able to make, casually, is limited and the most frequent views are of distant birds quartering their hunting grounds in search of prey, or of perched, inactive individuals at or near the roost. Though not without interest, such observations provide only a brief insight into the behaviour of the species, and a closer approach is necessary if one is to become more deeply acquainted with one’s subject. It is with the onset of the breeding season that this becomes practicable, for not only do the birds become more active, vocal, and easier to locate, but the observer is able to work from the cover of a hide and to watch the more intimate details of the owl’s life as long as certain rules are adhered to (see Appendix 3, Watching the Barn Owl).

THE BREEDING SEASON

During our study we have defined the breeding season as that period when serious courtship occurs and when either eggs or young are present. In our experience the end of the breeding season is usually heralded by the onset of the annual moult, and once this becomes apparent it can be reasonably assumed that one or both of the pair has lost condition and that further breeding activity is unlikely. When a second brood is produced the moult of the body feathers is either postponed or dispensed with altogether, depending on how late in the year the adults are freed from their parental duties. Unfortunately there appears to be no data on the way the moult proceeds in those races which breed continuously throughout the year.

The length of time a Barn Owl takes to hatch and rear its young to full independence is extraordinary, for a newly laid egg will not produce an independent owl in less than fourteen weeks. Add this to the several weeks during which the birds engaged in pre-nesting behaviour and the fact that the youngest of a brood of five will be at least eight days behind the eldest, and one can appreciate the remarkable amount of time devoted to breeding. The British Barn Owl T. a. alba is often quoted as breeding in every month of the year except January (e.g. Prestt in Gooders et al 1969, Fitter et al 1969, Prestt & Wagstaffe in Burton et al 1973); yet our own fieldwork and searches through the literature have failed to reveal any first-hand evidence of a clutch being started in Britain in January, September, October, November or December, so presumably these records refer only to the presence of eggs or young, and will in most cases mean that the observer has found owlets in the later stages of development.

The case is not so simple with other races, for it has been shown that many of these will breed throughout the year where conditions and prey availability make this possible. Thus T. a. affinis has been recorded as rearing four broods in Rhodesia, with the eggs of the second and third broods being laid while the young of the previous broods were still in the nest (Wilson 1970). T. a. hellmayri breeds throughout the year in Surinam, the main breeding season being from August–December, with second broods being started in January and some nests being found in the period March–May (Haverschmidt 1962). The picture with the American Barn Owl T. a. pratincola is even more complicated. In the north-eastern States it breeds throughout the year (Henny 1969), whereas Wallace (1948) states that in New York the Christmas Census workers could normally depend on finding unfledged young at some site or other. In Michigan it may breed almost continuously during peak years of the Microtus cycle, downy young having been recorded in the nest in every month of the year. However, when its staple prey is scarce it slows down, or may even miss a breeding season altogether. We should also mention that captive British Barn Owls of the race T. a. alba do not breed continually even when over-abundant food is offered. This seems to indicate that prey abundance is not the only factor affecting the breeding season – weather conditions and time of year also play a part.

In contrast to north-east America the breeding season is very short in California, i.e. January–June, with 50% of clutches being started between 9th March and 16th April (Bent 1938). F. Gallup (in Stewart 1952) pointed out that this correlates with the rainy season when vegetation is lush and prey plentiful. Such a short breeding season naturally precludes second broods and indicates the great variation which can occur amongst individual races in different parts of their range.

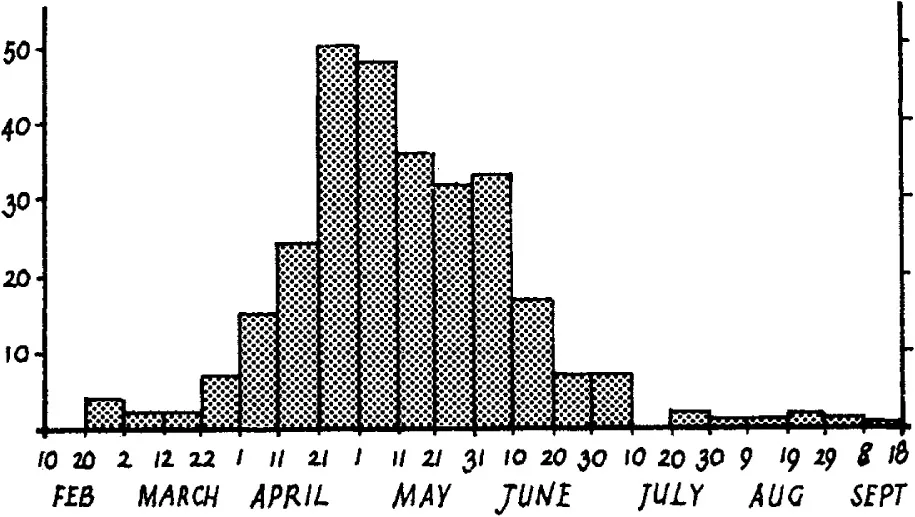

The data contained in 291 British Trust for Ornithology nest record cards covering England, Wales and Scotland during the period 1942–75 reveal no evidence of a connection between the dates of laying and the geographical location of British nests; Fig. 6 summarises the laying period as shown by these cards (after Glue, in prep.).

As can be seen, in Britain the months of April, May and June account for 92·4% of nests, the mean laying date being 9th May. There is, of course, a very good reason for this: the stage at which the young from these nests are most demanding in their food requirements coincides with the rodent population peak in July and August. This ensures that a regular, easily captured supply of prey is available, created by the relative abundance of young, inexperienced – and hence less alert – animals.

Fig. 6 Dates of first eggs at 291 Barn Owl nests in Britain (after Glue, in prep.).

We suspect that it is nests begun during the later months of the breeding season (i.e. in July and August), many of which are probably replacement clutches, that give rise to most of the reports of so-called second broods. The young from such nests will still be at and around the nest sites in November and December, and anyone unfamiliar with the Barn Owl’s breeding biology could be forgiven for assuming that they are the progeny of second broods. However, as we shall see later, second broods are a rather rare occurrence in Britain. There may be many reasons for genuine first clutches being delayed until so late in the season. Disturbance at the nest site, when no alternative suitable breeding place exists in the territory; temporary shortage of prey due to bad weather; and conditions which adversely affect the habitat and result in the hen obtaining insufficient food to stimulate laying, seem the most obvious and likely.

COURTSHIP

As we mentioned in Chapter 3, some pairs remain at the nest site throughout the year, roosting together and indulging in activities which maintain the pair-bond – mostly mutual preening and conversational chirruping and squeaking. However, other pairs carry on a looser association whereby both stay in the breeding territory but occupy different roosts. In our experience the latter is the commoner occurrence. They pay periodic visits to each other and also meet during their nightly excursions, maintaining the pair-bond in this way. Sometimes one of the pair apparently deserts the breeding territory (or dies), leaving the other bird alone. It is not only the cock which remains as territory-holder, for we have known of instances where the hen stayed as sole occupier of the breeding territory during the winter. Other pairs move away from the nest site together, usually after disturbance, and occupy a new roost in another part of the territory. They may even change the extent of the territory itself, taking in new ground if this is unoccupied by other Barn Owls, and abandoning once favoured haunts. In such cases the pair may still return to the traditional nest site at the onset of the breeding season, usually in early March, as the attachment to this is very strong and it is the focal point of any territory.

It is by no means unusual for Barn Owl pairs to use the same nest site for up to twenty or thirty years and there are several records, which seem reasonably acceptable, of up to seventy years. Ringing data and our own experiences show that when one of the pair succumbs the remaining bird may stay until it is joined by another mate, which sometimes takes place in the season that the former partner was lost (Baudvin 1975). This may still occur even when mates disappear in successive years, with the result that the site continues to be occupied. Several instances were recorded by Baudvin where both partners had changed in two years. In those areas of Europe where T. a. alba and T. a. guttata are both to be found (i.e. eastern France and western Germany) the choice of a partner of the other race is a matter of chance and many intermediate forms result.

Certain sites seem to have a special attraction for Barn Owls and are re-occupied by itinerant birds when they are found to be vacant due to the death or departure of the original birds. Since the species is by preference sedentary, a pair which leaves its winter roosts and returns to a breeding site in spring normally includes at least one of the previous season’s breeders; but despite all these variations in the behaviour of wintering birds, it is rare for a breeding territory to be deserted by both birds, unless some unfavourable change takes place within the habitat.

If conditions are suitable, true courtship may begin in late February. One of the first indications is an increase in the number of daylight sightings of normally nocturnal cock birds as they hunt for prey to present to their mates. The frequent screeching song flights of the cocks as they patrol their territories at dusk and after dark, are another sure sign of courtship activity, serving both to repel neighbouring cocks and to attract the opposite sex. It is by no means unusual to see the pairs associating together at night, and they begin to indulge in the sexual chases which are such a feature of Barn Owl courtship. In these, the cock persistently follows the hen wherever she goes, the two turning, twisting and weaving in a most intricate manner, often at great speed. Occasionally the cock follows the hen in a more leisurely manner, flying approximately two to six metres above and a little to the rear of her. Although silent chases do occur, the birds usually screech frequently during these activities, the hen’s broken, more screaming voice being readily distinguishable from the pure ‘pea-whistle’ screech of the cock. Her indescribable utterances at these times may properly be classed as our wailing – see Chapter 2, Call 3.

Two other display flights are performed by the cock in courtship. In one of these, which we have termed the moth flight, the cock hovers in front of the perched hen at the level of her head, retaining this position with legs dangling for a period of up to five seconds. In all the cases observed by us the cock faced the hen, so exposing his white underparts and underwings. On several occasions wing-clapping has been heard during this display but, as was explained in Chapter 2, we are not altogether convinced that this is a deliberate part of the performance because we have sometimes seen captive birds clap their wings together involuntarily while flapping hard in a confined space. In our observations the wing-clapping of the Barn Owl could not be compared with the more familiar loud wing-clapping displays of the Long-eared and Short-eared Owls: the cock Barn Owl merely produced a double flipping noise, the first sound being louder than the second, and although the claps were clearly audible they were only moderately loud. On one occasion a single wing-clap was heard during a suspected aggressive display when two owls mounted in the air facing each other, and it is perhaps significant that in such a performance the wing action would be particularly strenuous as during the moth flight. However, that such wing-clapping – whether true display or unintentional – is a rare element of Barn Owl behaviour is illustrated by the experiences of D. Scott who, in fifteen years, worked through seven complete nest cycles and spent from two to eight weeks at nests of five other pairs. He informs us that during all this time he only observed wing-clapping on four occasions, and two of these were by the same bird. Contrary to our own experiences he describes the wing-clapping on one occasion as being ‘such a clatter that it was audible at fifty yards’.

Although two of our own observations were made in the early part of the year, most of the cases of wing-clapping known and reported to us have occurred when the owls had young in the nest. One such observation by Scott is reproduced in full because of its exceptional interest: ‘The nest was twelve feet up in the side of a haystack. The hen was brooding very small young and the display took place fifteen minutes before dark. The cock appeared and pitched on to a branch of the tall hawthorn tree behind and to the left of the hide. He had a vole in his beak and sat for five minutes being mobbed by a cock Blackbird and a pair of Robins. The cock then flew into the nest-hole and deposited the prey. He flew out immediately and alighted on the same branch. A moment later the hen left the nest and flew to the top of the stack where she began to sway and vibrate her wings, her face pointing upwards towards her mate whose elevation was slightly higher. The cock suddenly launched himself from his perch, paused in mid-air, lifted his wings high above his head and smacked them together. He then flew to the hen’s side and copulated’.

We are also grateful to J. G. Goldsmith for informing us of a quite different method of wing-clapping to that we have described. He writes: ‘I have but a single observation of “wing-clapping”, at Caistor St Edmund’s, Norfolk, where one was crossing over an area of woods, with pasture in the middle which was occasionally hunted and which contained a tree in which they nested one year. It flew higher than I have previously seen one fly (about 45–50 m) and performed a spiralling circular flight with exaggerated clapping wing beats, before rising again and continuing over the next piece of woodland.’

The Barn Owl is not the only species for which a moth flight has been recorded. Mountfort (1957), in his monograph of the Hawfinch, refers to the moth flight performed by that species and describes it as a ‘queer, fluttering flight, but with shallow wing-beats’. It has also been noted in the Serin and occasionally in the Chaffinch, while Conder (in Mountfort) refers to the Goldfinch performing such a display.

The second type of aerial display seen at this time we have termed the in-and-out flight. In this the cock repeatedly flies in and out of the nest site in order to entice the hen into it: he flies out, circles around screeching, then swoops back inside. His calling from within usually has the desired effect of attracting the hen to him, but if this fails he may resort to a song flight. Occasionally, when...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright page

- Contents

- List of photographs

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Chapter 01 - Description and adaptations

- Chapter 02 - Voice

- Chapter 03 - General behaviour

- Chapter 04 - Food

- Chapter 05 - Breeding

- Chapter 06 - Movements

- Chapter 07 - Factors controlling population, and possible conservation measures

- Chapter 08 - Distribution in the British Isles

- Chapter 09 - Folk-lore

- Appendix 01 - Vertebrate species in the text

- Appendix 02 - Development of young Barn Owl

- Appendix 03 - Watching the Barn Owl

- References

- Plates

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Barn Owl by D.S Bunn,A.B Warburton,R.D.S Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.