![]()

1 THE SHIP

The function of sea transport, like that of any other form of transport, is to move things. Its success lies in finding people who have things to move and in its ability to move them safely and efficiently.

Logically one should start with what, where to and how much has to be moved by sea. However, before we can make any really useful analysis, it is probably better to appreciate what vehicles and hardware are at our disposal and to understand the basic jargon which has inevitably grown up around what must surely be the oldest form of transport.

The number and classification of ships

In the 17th century much of the business of the Port of London was conducted in various coffee houses in the city. One such coffee house, much frequented by people concerned with the shipping business, especially underwriters, was run by a man called Edward Lloyd. Anxious to please his clientele, he produced ships’ lists giving some account of vessels likely to be offered for insurance. Lloyd’s Register is a descendant of these lists and in four large volumes it contains details of all the merchant ships in the world of over 100 tons gross. In 2009 this total was well over 116,000 ships and, as is shown in Chapter Two, is made up of a large variety of types, shapes and sizes.

Ships can be categorised not only by their specialist functions, ie tankers, general cargo, containers etc, but also by how they are operated.

There are two basic modes of operation. A ship can be employed as a liner; that is, it runs on a regular line between two ports or series of ports. It has a regular schedule of sailings and an agreed list of tariffs or prices. Alternatively a ship can be employed as a tramp. In this case the ship is chartered or hired out at the best price the owner can obtain. Such a ship may go anywhere with anything.

There is, in fact, a third possibility where merchants or organisations who have a lot of cargo to move, such as oil companies, operate their own ships.

A further tradition is to distinguish, for a variety of reasons, between ships which go a short distance, referred to variously as coasters, home traders or short sea traders, and those which venture farther afield and are known as foreign-going ships (this will be dealt with in greater detail in Chapter Four).

Design and classification societies

Ships are designed by naval architects and they are bound by various constraints, such as the cost of different designs, what is technically possible, what cargoes they are most likely to carry, environmental safety and what ports they are most likely to trade between. The whole problem of planning is made more difficult by the fact that the design, ordering and building of a ship may take two or three years, and also that the expected working life of a ship is still in the region of 15 to 20 years. Obviously in the modern world much can change during this lapse of time.

Many shipowners have their own particular preferences and style, and as few ship types are mass-produced, there is considerable room for manoeuvre here on superficial appearances such as the shape of the superstructure and funnel. Underwater the shape of the hull is critical and is not left to artistic whims. Wax models are made and tested in special testing tanks. Being wax, their shape can be easily altered and retested and an optimum shape is evolved for the required size and speed and the anticipated sea conditions.

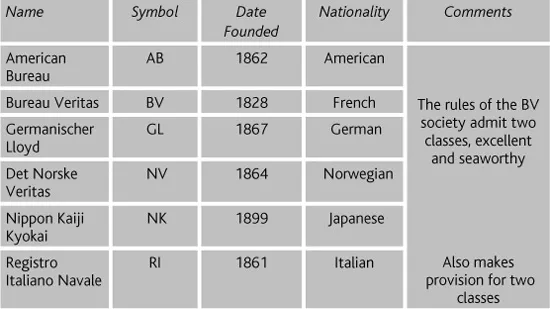

But the ship must not only be efficiently designed, it must also be soundly built, and the certificate of an independent body as to quality of design and construction may help a shipowner to convince an insurance underwriter that his ship is seaworthy. Such independent bodies are known as ‘classification societies’. There are numerous societies but the oldest, one of the largest and perhaps most famous, is Lloyd’s Register. (Edward Lloyd made comments on the state of the ship in his original circulars.) There is an International Association of Classification Societies (IACS), founded in 1968, and IACS members classify around 90% of the world’s gross tonnage. (IACS consists of ten member societies and one associate.) In 2005 IACS agreed common shipbuilding rules which came into force in 2006. There are about 40 small classification societies which are not all IACS members.

In its original state, when the Register was started in 1760, it was known as the ‘green book’ and it was for the exclusive use of underwriters. Some years later a rival register was started by shipowners, but in 1834 the two registers were reconstituted completely to form an independent society and a definite system of classification was started, based on a book of rules. In its early days there were many classes (A.1, representing the highest class, first appeared in 1775), but now there is only one class for all types of ocean-going vessel, 100 A1. (There are, however, four classes of ice-strengthening in the rules – vessels which are required to navigate in ice need to be strengthened accordingly, particularly round the bows and stern, which are the most vulnerable areas when battering their way through. The degree of strengthening depends on the severity of ice anticipated, and charterers and operators need to know not only these rules, but also the weather expected.)

Note: In early 2005 the IMO proposed goal-based standards on ship construction to avoid anomalies between the minimum standards of construction that exist between the different bodies concerned.

Table 1.1 Some notable classification societies

To obtain Lloyd’s class of

100 A1 the vessel must be built under the scrutiny of the society’s surveyors (the significance of the Maltese cross) and its strength and construction must satisfy the society’s rules. Similar conditions apply to the machinery of the vessel.

To maintain this class a vessel must undergo regular periodical surveys, which become more rigorous as the vessel ages. Engines, machinery parts, boilers, screw shafts and a variety of specific items, depending on the type of ship, are also subject to periodical surveys in accordance with the society’s rules.

In the UK, classification is voluntary but few shipowners would or could operate without it. It is not only the underwriters that the shipowners have to convince of a ship’s seaworthiness but also the charterers, shippers, financiers, various cargo interests and the port state authorities of the countries the ship will visit.

Finally, Lloyd’s Register includes all ships over 100 tons gross, whether classed with Lloyd’s or not, and is often referred to as the ‘shipping man’s bible’. It is obviously important to be familiar with its format and content. The key shown at the top of the specimen page has been inserted to help identify the data. In the actual volumes the key is printed in detail in the introduction to each volume. The Register of Ships is now available on a DVD and subscribers can access a daily updated version via the Internet. The DVD is virtually an encyclopaedia of shipping as it also includes ships on order, marine-related companies, 9,800 ports and a maritime atlas. The initial pages of the Register Book also contain a menu of information available to subscribers to Lloyd’s Register and Fairplay Ltd.

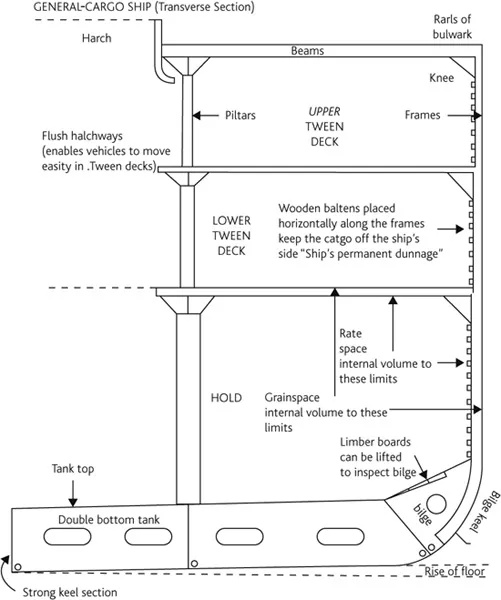

Parts of the ship (see Figs 1.1 and 1.2)

Figs 1.1 and 1.2 are typical of general-cargo ships built during the 60s. However, it is useful to show them in this section on definitions as they contain most of the basic elements found in modern ships. Many ship ‘definitions’ used in legal documents, such as charter parties, may well be decades out of date!

Although the figures are labelled ‘general-cargo ship’, ships, like cars and houses, can vary within certain very wide limits in their design and layout. Even the methods of construction can vary considerably from the traditional floor, frame, beam construction shown in Fig 1.1. Ships used to be built upwards and outwards from the keel. Now in most yards they are built in huge prefabricated sections which are subsequently joined together.

Anchors These are compulsory items of equipment. The usual arrangement is to have two bow anchors and one spare. They are raised and lowered by a special winch known as the windlass, or perhaps by a capstan on very large ships. The cable drops down off the windlass into the chain locker. A few ships have stern anchors. When considering an anchorage for a ship, the depth of water, the nature of the bottom and prevailing winds should be known. On long salvage tows the anchor cable is often used as part of the towing line.

Fig 1.1 Internal structure of a general-cargo ship.

Fig 1.2 Longitudinal section of a general-cargo ship.

Ballast This is weight loaded to make the ship seaworthy when she has to proceed to sea without cargo. Originally this could have been anything, often just sand and stones from the beach. However, modern ships use seawater in the double bottom tanks, peak tanks and also specially constructed ballast tanks.

Bilges (See Fig 1.2) These are virtually ditches at each side of the hold where all the condensation, sweat and leaking liquids can drain and be pumped out. Before any loading, particularly of foodstuffs, they must be cleaned out and inspected. On some ships the double bottoms are carried out to the sides, so there will be no bilges. When this occurs a ‘well’ or drain is made in an isolated section in the double bottom which serves the same purpose.

Bulkheads These are vertical partitions or walls. All ships must have a specified number of bulkheads, depending on their length. By dividing the ship into watertight divisions they reduce the danger of sinking if one compartment is holed. They also reduce the risk of fire spreading.

The forward bulkhead, called the ‘collision bulkhead’, is made particularly strong as it would have to withstand considerable buffeting if the ship steams to a repair yard having had her bows severely damaged in a collision. Had the Titanic hit the iceberg head-on instead of swerving and ripping a long gash down her side, she would almost certainly have made New York safely under her own power, instead of being the most terrible maritime casualty of all time. One of the problems of Ro/Ro ferries has been the large undivided car deck spaces which make them very vulnerable to flooding and to the subsequent loss of stability. Note the comments made under ‘Stability’ concerning ‘slack tanks’.

Decks The number of decks depends entirely on the trade and cargo for which the ship is designed. On some liner trades she may have three or four; passenger ships will have many more. Ships designed to carry cars may have several portable decks. On the other hand, tramp vessels carrying bulk cargoes may only have one deck.

Deep Tanks These are holds with facilities such as wash plates, pipelines and oil-tight hatches so that they can be used for the carriage of liquid cargoes or water ballast.

Derricks or Cranes These are used on general-cargo ships to lift the cargo on and off. They are usually capable of lifting between five and ten tons but the ship may be fitted with one or more heavy-lift derricks (‘Jumbo’) to cope with the heavier items of cargo. Derric...