![]()

Chapter One

Introduction

1.1 What are Multimodal Corpora and why use them?

Current methodologies in corpus linguistics have revolutionized the way we look at language. They allow us to make objective observations about written and spoken discourse. Large-scale, multi-million-word spoken and written corpora provide the user with an invaluable resource for generating accurate and objective analyses and inferences of the ‘actual patterns of [language] use’ (Biber et al., 1998: 4). They provide the apparatus for investigating patterns in the frequency of occurrence, co-occurrence (collocation) and the semantic, grammatical and prosodic associations of lexical items across large records of real-life discourse. These enquiries are difficult to carry out manually.

Consequently, ‘corpus analysis can be a good tool for filling us in on “the big picture”’ of language (Conrad, 2002: 77), providing users both with sufficient data for exploring specific linguistic enquiries, the corpora, and with the method of doing so; the corpus linguistic approach (see Stubbs, 1996: 41). However, widely used current corpora have a fundamental deficiency, insofar as, whether the corpus is based on written or spoken data, they all tend to present data in the same physical medium: text-based records. They are monomodal.

When using traditional text-based corpora, it has been notoriously difficult, practically impossible, to fully combine an investigation of patterns of discrete items, units of behaviour (as is common to corpus-based analysis), with descriptive frameworks of the functions of these units (as is common to pragmatics) when analysing real-life interaction (see Adolphs, 2008: 6–8). That is, it is difficult to fully assess the importance, that is, the ‘added value’ of analyses, which have primarily focused on classifying the ‘meaning of the actual language form or “sign” used’ with ‘other sources of knowledge, such as knowledge about the context of the situation, knowledge about other speakers or listeners and knowledge about culturally recognized norms and activities’ (Knight and Adolphs, 2008).

This is because contextual information is effectively ‘missing’ (see Widdowson, 2000; Mishan, 2004 and Mautner, 2007) in such ‘units’ of behaviour when using a basic corpus linguistic approach, given that discourse is stripped to its lowest common denominator, that is, that of text. While metadata and other forms of data coding, for example, can help to inform us of the identity and biographical profile of who was speaking to whom and where this conversation took place, this supplementary record effectively still ‘presents no more than a trace of the original discourse situation’ to which it pertains (Thoutenhooft, 2007: 3, also see Adolphs, 2008 and Knight and Adolphs, 2008).

The ‘reality’ of the discourse situation is thus lost in its representation as text. For example, communicative gestures and paralinguistic properties of the talk are lost during this process. This is problematic, because an understanding of the context of interaction is not only vital for the investigation of vocal signals, the words spoken (see Malinowski, 1923; Firth, 1957 and Halliday, 1978), but also for understanding the sequences of gesture used in discourse. For ‘just as words are spoken in context and mean something only in relation to what is going on before and after, so do non-verbal symbols mean something only in relation to a context’ (Myers and Myers, 1973: 208).

This book explores an emergent solution to this problem: the utility of multimodal datasets in corpus-based pragmatic analyses of language-in-use (for further discussions on pragmatics and corpora, see Adolphs, 2008). As Lund notes (2007: 289–290):

When discussing multimodal research and multimodal corpora, we are essentially looking not only towards the ‘abstract’ elements in discourse – the processes of ‘meaning making’ (i.e. bodily movement and speech, see Kress and van Leeuwen, 2001) – but also the ‘media’, the physical mode(s) in which these abstract elements are conveyed. Thus, as Lund notes, since ‘the mode of gesture is carried out by the media of movements of the body’ (2008: 290, paraphrased from Kress and van Leeuwen, 2001), it seems logical to define the multimodal as a culmination of these senses of the abstract and the media.

So while multimodal behaviours (in interaction) are involved in the processes of meaning generation, the multimodal corpus is the physical repository, the database, within which records of these behaviours are presented. This is achieved through the culmination of multiple forms of media, that is, different modes of representation. Thus, the ‘multimodal corpus’ is defined as ‘an annotated collection of coordinated content on communication channels, including speech, gaze, hand gesture and body language, and is generally based on recorded human behaviour’ (Foster and Oberlander, 2007: 307–308).

Aims of this book

Fundamentally, this book champions the notion that ‘multimodal corpora are an important resource for studying and analysing the principles of human communication’ (Fanelli et al., 2010). It outlines the ways in which multimodal datasets function to provide a more lifelike representation of the individual and social identity of participants, allowing for an examination of prosodic, gestural and proxemic features of the talk in a specific time and place. They thus reinstate partial elements of the reality of discourse, giving each speaker and each conversational episode a specific distinguishable identity. It is only when these extra-linguistic and/or paralinguistic elements are represented in records of interaction that a greater understanding of discourse beyond the text can be generated, following linguistic analyses.

Multimodal corpus linguistics remains a novel and innovative area of research. As discussed in more detail in Chapter 2, large-scale multimodal corpora are still very much in development, and as yet no ready-to-use large corpus of this nature is commercially available. Correspondingly, publications that deal both with multimodal corpus design and the systematic analysis of the pragmatic functions of particular spoken and non-verbal features of discourse, as evidenced by such corpora, are somewhat scarce. The current volume helps to fill this void.

This book provides an examination the state-of-the-art in multimodal corpus linguistic research and corpus development. It aims to tackle two key concerns, as follows:

Developing multimodal linguistic corpora:

Using multimodal linguistic corpora:

In short, the volume provides a bottom-up investigation of the issues and challenges faced at every stage of multimodal corpus construction and analysis, as well as providing an in-depth linguistic analysis of a cross section of multimodal corpus data.

Modes of representation in multimodal corpora

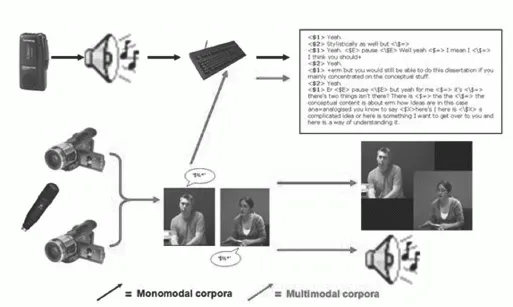

The majority of current multimodal corpora, including the NMMC (Nottingham multimodal corpus, see section 1.2 for more details), the corpus used for the main studies carried out in this book, represent records of communication across three different, integrated modes (although metadata is often stored as part of the database, as discussed below). As listed below and illustrated in Figure 1.1.

FIGURE 1.1 Monomodal versus multimodal corpora

The integration of textual, audio and video records of communicative events in contemporary multimodal corpora provides a platform for the exploration of a range of lexical, prosodic and gestural features of conversation (the abstract features, see Kress and van Leeuwen, 2001), and for investigations of the ways in which these features interact in real, everyday speech. For, as Safertein notes:

Current multimodal corpora

Unlike monomodal corpora, which have a long history of use in linguistics, the construction and use of multimodal corpora is still in its relatively early stages, with the majority of research associated with this field spanning back only a decade. Given this, ‘truly multimodal corpora including visual as well as auditory data are notoriously scarce’ (Brône et al., 2010: 157), as few, for example, have been published and/or are commercially available.

This is owing to a variety of factors, but is, primarily, due to ‘privacy and copyright restrictions’ (van Son et al., 2008: 1). Corpus project sponsors or associated funding bodies may enforce restrictions on the distribution of materials, and prescriptions related to privacy and anonymity in multimodal datasets further reinforce such constraints. Although, notably, plans to publish/release data contained within the D64 corpus (detailed below, see Campbell, 2009) and NOMCO corpora (an ‘in-progress’ cooperative corpus development project between Sweden, Denmark and Finland focusing on human-human interaction, see Boholm and Allwood, 2010) have been confirmed for the near future, these have yet to come to fruition.

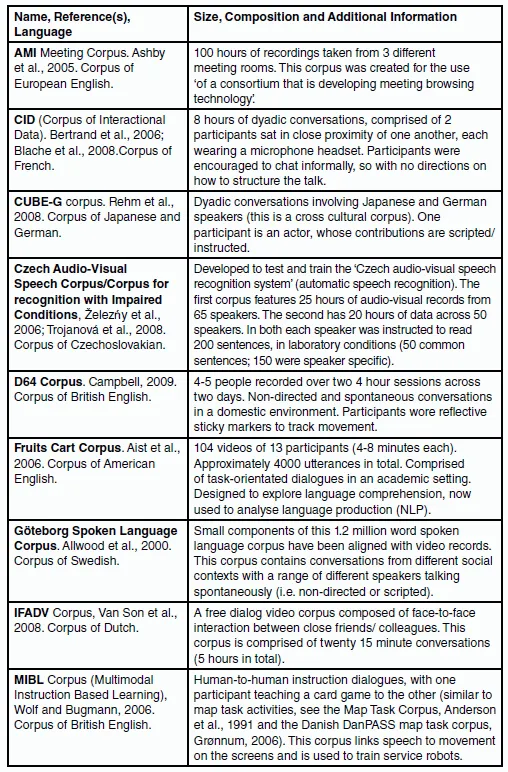

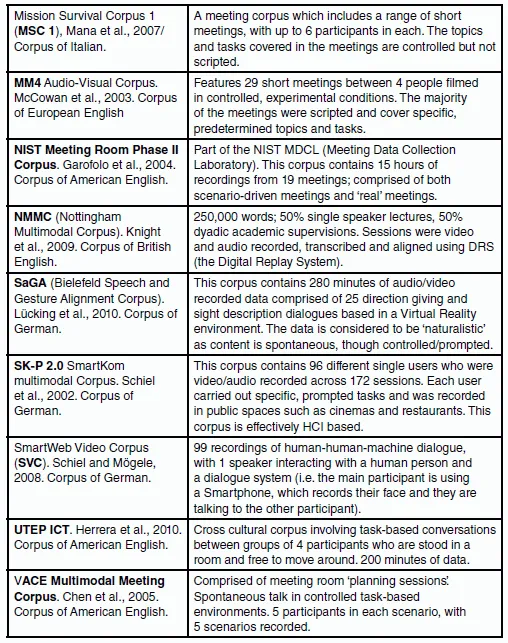

Despite this, a range of different multimodal corpora does exist. An index of some multimodal corpora and corpus projects is provided in Figure 1.2. The majority of the corpora presented in Figure 1.2 are both not freely available, and focus on other registers aside from English. These corpora will, however, be alluded to throughout this book in order to provide evidence and/or support to claims being made, so they are worth noting here.

Figure 1.2 An index of multimodal corpora.

The majority of the corpora presented in Figure 1.2 are both not freely available, and focus on other registers aside from English. These corpora will, however, be alluded to throughout this book in order to provide evidence and/or support for claims being made, so they are worth noting here.

Some of the corpora presented in Figure 1.2, such as the CUBE-G, contain communicative data from participants with different first languages. These allow analysts to provide a cross-linguistic multimodal perspective of discourse. Others have been designed to explore a range of different topics, or to answer specific linguistic or technological questions. These specific compositional characteristics of these corpora are discussed in more detail in the following chapter of this book.

The Nottingham multimodal corpus (NMMC)

The corpus used in the present text (included within Figure 1.2) both as a means for articulating some of the challenges faced in the construction of multimodal corpora (based on actual experiences), and for carrying out the detailed analysis of signals of active listenership, that is, backchanneling phenomena, is the NMMC: the Nottingham multimodal corpus. The NMMC was built as part of the interdisciplinary ESRC (Economic and Social Research Council) funded Understanding Digital Records for eSocial Science (DReSS1) project, which involved staff from the School of Computer Science and IT, School of English Studies and School of Psychology at the University of Nottingham. The linguistic concern of this project was to explore how we can utilize new textualities (multimodal datasets) in order to further develop the scope of corpus linguistic analysis. It examined the linguistic and technological procedures and requirements for constructing, hosting and querying multimodal corpora.

The NMMC is a 250,000-word corpus compiled between 2005 and 2008. It is comprised of data sourced from an academic setting, that is, from lectures and supervision sessions held at the University. Fifty per cent (circa 125,000 words) of this corpus involves single-speaker lectures and 50% are dyadic conversations between an MA or PhD student and their supervisor. There are a total of 13 video and audio recorded sessions for each strand of the corpus. The lectures average around one hour in length, amounting to between 5,500 and 12,500 words of transcribed data, whereas the supervision data ranges between 30 and 90 minutes of video, and 4,500 to 12,000 words of transcribed data. A 5-hour, 56,000-word sub-corpus of the multimodal supervision data is used in the analysis of backchanneling phenomena in Chapters 6 and 7.

1.2 From Early Corpora to a Multimodal Corpus Approach

A corpus linguistic approach is an empirically based methodological approach to the analysis of language. Although the term ‘corpus linguistics’ is relatively new, emerging around 1955, McEnery and Wilson indicate that ‘the methodological ideas, motivations and practices involved in corpus linguistics in fact have a long history in linguistics’ (1996: 1). Indeed, there are many examples of early empirical studies that explored patterns of actual language-in-use. For the most part, these involved scholars working with hand-written, purpose-built collections of texts (corpora), which took an enormous amount of time and effort to design, build and analyse.

Corpus studies of this nature included those examining the lexicographical and grammatical properties of language (Käding, 1879; Boas, 1940), studies of language acquisition (see Ingram, 1978), learning and teaching (see Palmer, 1933; Fries and Traver, 1940; Bongers, 1947) and biblical studies. Corpora in this ‘pre-electronic’ phase were relatively small, and as they were manually construc...