![]()

1

History of Ethics

Chapter Outline

Aristotle on eudaemonia and virtue

Some themes from Hobbes and Hume

Some Kantian themes

John Stuart Mill’s utilitarianism

Section 1: Aristotle on eudaemonia and virtue

1. Aristotle on the good

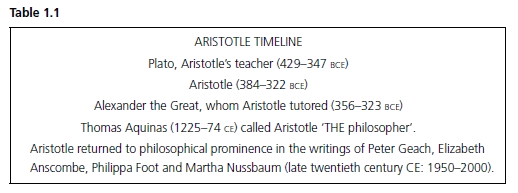

Aristotle’s best-known book on ethics, the Nicomachean Ethics (see below), was intended to give practical guidance for life in the real world. His world was different from ours, for he had been the tutor of Alexander the Great, and lived and lectured in classical Athens. Yet he wrote to help people reason reflectively about the good life and the good community, and what is attainable within them. He wanted to avoid abstract theories such as those of his teacher, Plato, about ideals like the form of the good (or ‘the Good Itself’), something which was supposed to embody what was common to everything that is good. Such theories, even if they made sense, were in his view of no practical help; they gave no clues about what kind of life is worth pursuing. What he put forward instead is widely considered highly relevant to the modern world and to all varieties of human society, so much so that he is currently one of the more influential of historical philosophers and ethicists. See Table 1.1.

Aristotle opens Book I by declaring that ‘the good’ is what everyone and every action and enterprise aims at. There is a deep truth here, for there does seem to be some necessary (or non-contingent) connection between ‘what is aimed at’ and ‘good’. He proceeds to explore what this good consists in, both for individuals and for communities. After considering and sifting opinions, he presents two criteria or requirements for successful specifications of the good. Nothing will be the good unless it is ‘final’; that is to say, it is always chosen for its own sake and never for the sake of something else. There again, nothing will be the good unless it is self-sufficient; that is to say, it is in no way incomplete or lacking, and unable to be supplemented in point of desirability by anything else, as if it were just one good among others. These requirements eliminate most of the usual particular candidates for being the good, such as wealth or reputation or pleasure (see Book I, chapters 1 to 7).

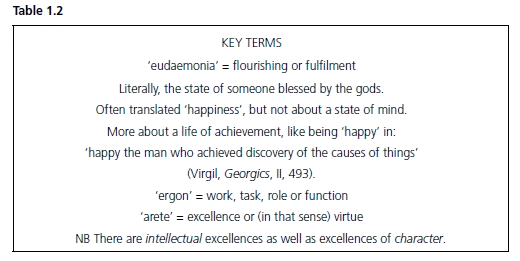

Aristotle deduces in chapter 7 that the good for human beings consists in ‘eudaemonia’ (literally ‘blessedness’) or human flourishing or fulfilment (sometimes inaccurately translated as ‘happiness’), for eudaemonia uniquely satisfies these requirements. Further, his conclusion about what actually comprises eudaemonia, reached through an argument to be mentioned shortly, is that it consists in activity of the soul (i.e. psychological or mental activities) in accordance with excellence, or, if there are a number of excellences or virtues, then with the best or most perfect of them; and indeed in a lifetime of such activity, for ‘one swallow does not make a summer’. For eudaemonia, the liver of such a life must also have friends and a modicum of resources, or we would not say that he or she is flourishing. (Aristotle probably had just males in mind, for the activities of women were severely limited in Greek society.)

His argument for this conclusion runs as follows. Each kind of person has a final end, specific activity or function (‘ergon’ in Greek); thus that of a harp-player is to play well, just as that of a shoe-maker is to make good shoes. So it would be surprising if human beings did not have a function as such, which belongs to them simply as humans. This function will not be any of the capacities shared with other species, such as that of growth (shared with plants), or mobility (shared with other animals). The capacity which is exclusively human is rationality, and so it is in the exercise of their rational powers that the specific activity of human beings consists, and that is where human excellence is to be found. We can now see how Aristotle reaches his account of ‘eudaemonia’ as ‘activity (of the soul) in accordance with excellence’. (The word for excellence, ‘arete’, is sometimes translated ‘virtue’, but his concept of excellence, as we shall see, is broader than what we usually mean by ‘virtue’, qualities of moral excellence, including as it does intellectual excellences too. In any case it is now apparent that the concept he needs is not a specifically moral one, but rather one involving high-quality functioning of distinctively human capacities.)

While Aristotle’s conclusion is far from absurd, his argument is widely held to be defective and inconclusive. The most striking problem is that on many views humans simply do not have a function, and so it is futile to go in search of one. Aristotle, for his part, believed that every distinct entity has a function, but this metaphysical view is not one that most of us share in. So his reliance on the premise that all humans have a function is misplaced. Yet maybe the argument can be repaired. For perhaps he was right to hold that human beings have certain essential capacities (including rationality), capacities in the absence of which they would not be human, and could go on to locate human excellence in the exercise of these capacities; if so, something like his conclusion could be reached without appeal to humans having a specific or characteristic function.

Another objection to Aristotle’s reasoning is that he appeals to distinctive capacities (and to psychological ones at that), whereas the essential capacities of human beings include many that are not distinctive, but are shared with other animals, such as sensory perception, mobility and reproduction. If the argument is to turn on essential capacities, then these non-distinctive ones should be recognized too, despite being in some cases physical rather than psychological ones. Indeed all of these capacities can contribute to human well-being, as they can to that of other animal species. Aristotle’s appeal to what is distinctive about human beings can beneficially be superseded and his theory broadened to include those other capacities in the absence of which we would not be recognizably human. (While Aristotle might well have resisted the modifications of this and the previous paragraph, they rest on a very Aristotelian basis, the importance of essential qualities.)

Another objection may now be raised. Well-being does not involve exercising every one of the essential human capacities. Thus we would not say that blind people or childless people cannot have a good quality of life just because they are blind or childless. To claim that human flourishing depends on exercising all the essential human capacities would be an insensitive exaggeration. Yet it remains plausible that quality of life depends on exercising most (or at any rate enough) of them. So Aristotle could still be substantially right.

One final criticism remains to be considered. In Book I, chapter 7, Aristotle makes the following addition to his conclusion that eudaemonia consists in ‘an activity of soul in accordance with excellence’: if there is more than one form of excellence, it will consist in ‘activity in accordance with the best and most complete form of excellence’. Subsequently, in Book X, he infers that this is in fact theoretical or contemplative reason. So, although most of the intervening books focus on excellences of character and also on practical reason (the kind of reason on which they all depend), he concludes in Book X that human flourishing really consists in a life of contemplation (such as the life of the philosopher) instead. But this makes him open to the criticism that his account of human flourishing is too exclusive, and should admit other excellences (such as virtues of character), and friendship too. (See the articles of Hardie and Ackrill, listed under ‘Further Reading’.)

This criticism can be expressed in Aristotle’s own terms. In Book X, he claims that a life of contemplation is self-sufficient because it is relatively immune to life’s vicissitudes. But this reasoning changes the meaning of ‘self-sufficient’ from that of Book I. ‘Self-sufficiency’ there meant that a self-sufficient good cannot be enhanced through any form of supplementation, and any account of it would have to be an inclusive one. But a life of contemplation can be enhanced through being supplemented by the presence of other excellences (such as courage and prudence) and with the inclusion rather than the omission of friendship. (These examples are ones Aristotle acknowledges in earlier books; you can probably suggest others.) So Aristotle’s eventual conclusion infringes his own self-sufficiency requirement. To put things another way, his addition mentioned at the start of the previous paragraph was misguided, and he would have done better to leave his account of ‘eudaemonia’ unqualified. See Table 1.2.

2. Aristotle on virtue

But this suggests that what Aristotle has to say about other excellences, such as excellences of character, is worth studying. (Many of his analyses of concepts have proved to be of lasting value; for his account of pleasure, see J. O. Urmson, ‘Aristotle on Pleasure’.) In Book II, Aristotle analyses virtues as dispositions to choose in accordance with reason (or a principle), dispositions which have been acquired through past choices. Practical or ethical virtues differ from intellectual ones in concerning actions or emotions, and involving practical wisdom, which Aristotle distinguishes from theoretical wisdom (Book VI, chapters 5 to 13). This is gradually developed through making practical choices. Aristotle’s account of the virtues in terms of dispositions, choices and reason has survived the test of time, and stands in marked contrast with accounts like that of David Hume which are indifferent to the role of choices and sceptical about the relevance of practical reason (see the part of the next section on Hume).

On the way to explaining the virtues, Aristotle analyses what we mean by ‘voluntary’ and by ‘choice’. Voluntary actions are ones that are neither coerced nor due to ignorance, and it is only voluntary actions that qualify for praise or blame (Book III, chapter 1; if only Aristotle’s incisive findings had been heeded across the centuries). But not all voluntary actions are chosen; for choices are accompanied by deliberation, in which people reflect on matters within their control in the light of goals or principles (Book III, chapters 2 and 3). Aristotle’s notion of choice or deliberate action is narrower than ours, involving the presence of deliberative reasoning. Yet while we might object that not all choices involve such deliberation, A. C. MacIntyre is right to comment that all choices can be appraised by the decisions that deliberation would have issued in (Short History, p. 74), and therefore that, as Aristotle holds, principles or understandings of the good are always relevant to them. So the development of character and of the virtues of character involves coming to behave as a person with such principles would do. (Can we help forming the characters that we do? Aristotle believes that we are answerable for them, but his discussion will be returned to in the chapter on Free Will.)

Yet how can we act virtuously (bravely or temperately, for example) at all, given that we do not begin life with settled characters? According to Aristotle, to act virtuously is to act as the virtuous person would act. But if so, how can we ever begin to be brave or to act with moderation? We can begin, Aristotle replies, if we are well brought up, and are led through rewards and deterrents to face problems, dangers or enticements as the virtuous person would do. By choosing to act in a virtuous manner not just once but recurrently, we acquire the related virtuous disposition (Book II, chapter 4). Whether or not moral education always follows this course (and despite there being some evidence of sudden changes of character), Aristotle’s dispositional view of the nature of virtue has continued to command widespread assent. His theory of virtue, however, as the mean between pairs of extremes (Book II, chapter 6), courage (for example) being a mean between cowardice and rashness, has proved more controversial. Indeed some commentators suggest that he is driven to invent extremes for the virtues to fit between, that his theory is a contrived rationalization of the virtues of his own society, and that some of his ‘virtues’ such as that of the self-important ‘great-souled’ man (Book IV, chapter 3) seem to bear out this criticism.

Problems include the difficulty of finding pairs of extremes (attitudes of excess and of defect) to match every virtue (as the mean between them). While a term for excessive indulgence in pleasures does not need to be invented, insensitivity to pleasure, as Aristotle acknowledges, is seldom to be found. And as he also concedes, some matters do not admit of moderation (adultery is a good example). Besides, Aristotle modifies his own theory: the mean is not a mathematical median, but ‘the mean relative to us’; just as the needs and circumstances of the average person and of heavy-weight wrestlers are different (and thus their diets too), so the doctrine of the mean must likewise take circumstances into account (Book II, chapters 6 to 8). But this betokens that the mean is in any case a matter of judgement.

This retreat, however, need not suggest that Aristotle’s whole theory of virtue is beyond redemption. For his virtues (or rather many of his virtues) answer to problems that recur in virtually every society, and some to problems in all, and arguably most of his virtues are qualities that are needed by everyone. As Martha Nussbaum has argued, people in all societies have in common problems such as facing situations of danger and opportunities for pleasure, and thus need virtuous dispositions like courage and self-control to cope with these recurrent spheres of experience, as much for their own good as for that of ...