- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

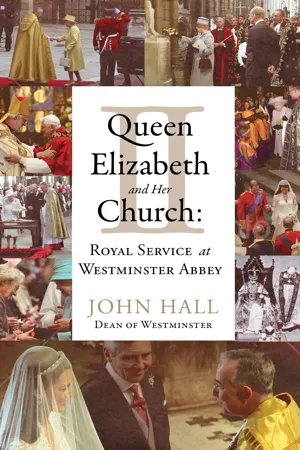

About this book

The Queen, when she was 21, declared that her whole life whether it was long or short would be devoted to service. At the coronation, she was set apart for service after the example of Jesus Christ. In Her Majesty's diamond jubilee year, the Dean of Westminster recalls the coronation, and special commemorations attended by The Queen in Westminster Abbey in recent years, including the marriage of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge (which reached a television audience of 2.2 billion people). He offers an insight into some very special occasions -- not all widely known -- and reflects on a pattern of leadership as devoted service.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Queen Elizabeth II and Her Church by John Hall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Anointing and Coronation

‘The fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control’ (Galatians 5: 22).

Joy

I was four at the time. It is one of my earliest memories. I was sitting with my parents, sister and brothers and various aunts around my grandparents’ eight-inch television screen, peering intently at a flickering black-and-white image. Now in an age of wide-screen high-definition colour television, it seems almost incredible that we saw anything. But there we were, eagerly watching the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. I remember a great sense of occasion, and a spirit of veneration, even of awe.

Countless family groups up and down the country were just like us, many of them watching TV sets newly acquired for the purpose. But this was much more than a moment in television history. It was a great royal ceremony, one to catch the eye and the imagination, with glitter, pomp and magnificence. George VI’s coronation in 1937 had been filmed for the cinema. Now for the first time, people had immediate access through the television to what was happening at the time. We could all feel we had some part in it. But I wonder how far the complex ceremonies and the rolling phrases in sixteenth-century English spoke to the audience in the Abbey, let alone in our homes, of what it all stood for, what it all meant.

Now that I am living and working at the Abbey, I have had a chance to sort things out in my own mind. For example, I have now seen exactly where the Coronation Chair was placed and which way it faced. I had scarcely given the question which way it faced a thought before I came to the Abbey, but I remember discovering to my surprise that the Chair faces the high altar. The Queen was crowned with her back to the congregation. Even the throne, high up in what I have discovered is called the coronation theatre, faces the altar. I suppose it should be obvious, but I had somehow assumed that the ceremony of coronation would be performed so that as many people as possible could see. In fact, there is a degree of privacy, of intimacy at the heart of the ceremony. The Sovereign faces the high altar, the most sacred part of the Abbey, just like the couple at a wedding ceremony. At a coronation, the engagement is between the Sovereign and God. That is the key relationship. The people have their role in the service, giving their assent at the beginning and later paying homage, but the exchange is between the Sovereign and God. The Sovereign offers an oath of loyalty and service. God offers the gift of grace and the anointing of the Holy Spirit. It is a mutual exchange of gifts, the Queen offering to serve God and her people and God offering in return to bless and uphold her.

There is ample public evidence that for Queen Elizabeth II at her coronation on 2 June 1953, this offering of service was well understood. On her 21st birthday, the then Princess Elizabeth broadcast from South Africa a radio message to the people of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth. She pledged herself then to commit her whole life ‘whether it be long or short’ to duty and service. She deliberately spoke in the most solemn words about going forward together ‘with an unwavering faith, a high courage, and a quiet heart’. Her aim was that the Commonwealth should be a ‘powerful influence for good in the world’:

To accomplish that we must give nothing less than the whole of ourselves. There is a motto which has been borne by many of my ancestors – a noble motto, ‘I serve’. I declare before you all that my whole life whether it be long or short shall be devoted to your service. But I shall not have strength to carry out this resolution alone unless you join in it with me, as I now invite you to do: I know that your support will be unfailingly given. God help me to make good my vow, and God bless all of you who are willing to share in it.

The Queen spoke in a similar way in a broadcast on the evening of her coronation:

Throughout this memorable day I have been uplifted and sustained by the knowledge that your thoughts and prayers were with me. It is hard for me to find words in which to tell you of the strength which this knowledge has given me.

The ceremonies you have seen today are ancient, and some of their origins are veiled in the mists of the past. But their spirit and their meaning shine through the ages never, perhaps, more brightly than now. I have in sincerity pledged myself to your service, as so many of you are pledged to mine. Throughout all my life and with all my heart I shall strive to be worthy of your trust.

Sixty years later the words ring as true as they did when they were first spoken, and nothing has occurred that would cause anyone to doubt the sincerity of the commitment that lay behind them or the strength of the faith and confidence in God’s call and anointing with which they were imbued.

I hope that by going into some of the details of the service itself in this chapter, I can show how the Coronation expresses with absolute clarity the fundamental values the monarchy represents, values which I am summing up in the phrase servant leadership, about which I shall say more later. It is worth reflecting that the Coronation service is not reinvented each time but follows a powerful tradition which has been sustained at the Abbey down the centuries. Every one of the key elements has remained present in the service through good times and bad, with sovereigns whose reign appeared to promise peace and prosperity and with sovereigns whose reign filled their contemporaries with dread.

One of the most precious objects in the Abbey’s archives is a fourteenth-century illuminated manuscript called the Liber regalis. This beautiful little book is an instruction manual for coronations and claims tenth-century authority. So the way a king or queen has been crowned in England has been unchanging in its essentials for well over a thousand years. In the Liber regalis are three forms of service for coronations: of a king; of a queen consort; and of a king and queen together. The last Saxon king Harold was crowned in the Abbey on 6 January 1066. The first Norman king, William I (the Conqueror), was crowned in the Abbey on Christmas Day that same year. Since then, all three versions of the coronation have been used at different times. Sometimes a king was married already when he came to the throne and his queen was crowned with him. On other occasions, a king was single and crowned alone. When he subsequently married, his queen had her own coronation, a ceremony that presumably became rather familiar to Henry VIII. There was no provision in the fourteenth-century for the reign of a queen. No queen had ever been crowned who reigned alone, nor would any until Mary I in 1553 and her sister Elizabeth I in 1558. As queens regnant, they were crowned using the form for a king. The three key elements of the service remain: the sovereign’s oath; the anointing; the crowning. They are always set within the context of the celebration of Holy Communion.

Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, the fourth in the twentieth century, took place on 2 June 1953, over a year after her accession to the throne on 6 February 1952. Those months of the Queen’s reign saw energetic preparations for the great event. These included the transformation of the Abbey during almost a year’s closure to visitors, which must have been an immensely strange and costly experience for the Abbey community. A wooden floor was laid over the stone floor of the Abbey and rail tracks laid down to allow building materials to be introduced. At the lantern crossing, where the north–south axis of the transepts meets the west–east main axis of the church, the Theatre was levelled with the Sacrarium itself, the space in front of the high altar, and an additional tier of steps lifted the Queen’s throne above the level of the coronation chair in the middle of the Sacrarium. Great tiers of seating in galleries were erected in the north and south transepts and around the quire and in the nave. It is possible to set out on the floor of the Abbey just over two thousand seats without putting at risk people’s ability to move around safely. The additional tiers of seating, on great scaffolds going very high under the ceiling, created enough space to accommodate 8,000 people in the Abbey. I find it hard to imagine the experience of being stuck high up under the ceiling for several hours. It must also have taken ages to get everyone in and out. Peeresses secreted sandwiches in their coronets.

The tension must have been considerable as the moment for the Queen’s entrance came closer. It was broken when someone came in with a carpet sweeper for the red carpet down the middle of the Abbey. Finally, the moment came with a heralding fanfare of trumpets.

The Queen’s entrance was marked, as at every coronation since 1902, by the choir singing Psalm 122 set to music by Sir Hubert Parry. The psalm was most probably written to celebrate the triumphal entry of the king and the people of God in ancient Israel into the capital city, the great city of Zion, Jerusalem, so revered by Jews, Christians and Muslims, and often understood as a powerful image of heaven. The psalm includes a prayer for peace and prosperity.

I was glad when they said unto me:

We will go into the house of the Lord.

Our feet shall stand in thy gates:

O Jerusalem.

Jerusalem is built as a city:

that is at unity in itself.

O pray for the peace of Jerusalem:

they shall prosper that love thee.

Peace be within thy walls:

and plenteousness within thy palaces.

The forty Queen’s Scholars of Westminster School have a historic right to shout Vivat Rex or Vivat Regina at the coronation: Long live the King or Long live the Queen. Parry modified the shout into a tuneful addition to the music of the anthem: vivat, vivat, vivat Regina Elizabetha. The anthem has been immensely popular over the past century and is frequently sung at services of all kinds, including a royal wedding. But the Vivats, which are inserted before the injunction to pray for the peace of Jerusalem, are only ever sung at celebrations of the Coronation in the presence of the Sovereign.

During the anthem, after her entry, the Queen moved to a chair on the south side of the Sacrarium and knelt in private prayer. Her prayer desk was just in front of the royal box, set up a little higher, where her mother and sister, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother and Princess Margaret, would later be accompanied by her children, Prince Charles and Princess Anne.

Then came the ‘Recognition’: a moment that reflects ancient history. When William the Conqueror died there was no certainty who would be the next king – a son, but which? William II, better known as William Rufus, was the Conqueror’s third son, and his successor, Henry I, the fourth son. Almost three centuries later, at the coronation on 13 October 1399 of Henry Bolingbroke who had deposed Richard II to reign as Henry IV, this recognition must have been a moment of confirmation. For certain subsequent monarchs too – as late as the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries – the succession was by no means uncontested. About Queen Elizabeth II’s right to the throne there was of course no doubt whatever. The Archbishop with the Lord Chancellor and Earl Marshal led the Queen to the four sides of the Coronation Theatre for the Recognition by the people, who responded with God save Queen Elizabeth.

Now that she had been recognized as Queen, the next step was for the Archbishop to administer the oath. The terms of the oath have changed over the centuries. Above all, the oath is a solemn promise to rule justly under God and to maintain the position of the Church, of the Christian faith at the heart of the nation. The position of the Established Church has been under attack for centuries, so the terms of the oath have been a matter of discussion. I learnt as a young boy that the longest word in the English language was antidisestablishmentarianism. The word was coined in the nineteenth century, when strong positions were being taken for and against the establishment of the Church of England, for and against its position as state church. Those who subscribed to antidisestablishmentarianism were opposed to the disestablishment of the Church and wanted to maintain things as they were. In the coronation oath the Queen promised to do just that. It is worth quoting in full.

Will you solemnly promise and swear to govern the Peoples of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, Pakistan and Ceylon, and of your Possessions and other Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining, according to their respective laws and customs?

I solemnly promise so to do.

Will you to your power cause Law and Justice, in Mercy, to be executed in all your judgements?

I will.

Will you to the utmost of your power maintain the Laws of God and the true profession of the Gospel?

Will you to the utmost of your power maintain in the United Kingdom the Protestant Reformed Religion established by law?

Will you maintain and preserve inviolably the settlement of the Church of England, and the doctrine, worship, discipline, and government thereof, as by law established in England?

And will you preserve unto the Bishops and Clergy of England, and to the Churches there committed to their charge, all such rights and privileges, as by law do or shall appertain to them or any of them?

All this I promise to do.

Laying her hand on the Bible, the Queen confirmed her oath, saying: ‘The things which I have here promised, I will perform, and keep. So help me God.’

The preliminaries over, it was time to begin the servic...

Table of contents

- Cover-Page

- Half-Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Anointing and Coronation

- 2 Servant Leadership: A biblical model

- 3 Abolition of the Slave Trade bicentenary

- 4 The Queen and Duke’s diamond wedding

- 5 Commonwealth Day observance

- 6 Remembrance

- 7 The Papal Visit

- 8 The Royal Maundy

- 9 The Royal Wedding

- 10 Servant Leaders: A way of life

- Postscript

- Index