![]()

Chapter 1

Theoretical Foundations

A fundamental goal of the research program developed under the generative tradition is to explain the human language faculty, that is, what does it mean to know a language. This inquiry has produced a vast body of research over the last three decades that seems to bring us closer to understanding language. Closely related to this topic is the issue of the initial state, that is, how do children acquire language and more specifically what, if anything, do they bring to the acquisition process and how do they converge to the target grammar. In this chapter, I address these two topics. The first part of the chapter starts with an overview of the theoretical linguistics framework adopted in this monograph, the Minimalist Program (MP) (Chomsky 1995, 2001) and how this approach can be applied to the acquisition of Spanish nominal agreement. The second part of the chapter focuses on some of the major proposals made in the literature regarding the initial state (continuous vs discontinuous approaches) and their predictions for the present study.

1.1 Agreement in the Minimalist Program

The Minimalist Program (Chomsky 1995, 2001) assumes a language faculty construct comprised of a cognitive system (which stores information) and a performance system (which access and uses this information). Similarly to the Principles & Parameters Approach (Chomsky 1981), the focus of inquiry in the MP framework is the cognitive system and its two components: the lexicon and the computational system. The lexicon stores Lexical Items (LIs) of a particular language, roughly speaking words, along with their idiosyncratic requirements or specifications. The computational system is where syntactic operations take place.

At the heart of the MP approach is the assumption that the locus of language variation is the lexicon (not the syntax), expressed in this system as feature specifications on LIs, for example, the specification of gender features in Spanish nominals. Notice that features of LIs may be phonological, semantic, morphological, or syntactic in nature. The MP also assumes that LIs, such as nominals, verbs, and adjectives come inflected and with their features already specified from the lexicon. For example, in the Spanish determiner phrase (DP) la casa bonita ‘the pretty house’ lexical items such as the nominal casa and the adjective bonita come from the lexicon inflected with the word marker –a and with the nominal features, in this example, feminine and singular already specified or what can be represented as [– masculine, + singular]. In contrast, functional items such as the determiner la do not come from the lexicon with these features specified or what can be represented as [masculine, singular]. Notice that in this last case, no values were given to these nominal features.1 For the present study, I assume that adjectives such as bonita come from the lexicon uninflected and with unspecified values for the gender and number features, and when they enter into an agreement relationship with the nominal they modify, the values of these features are inherited or specified to match those of the nominal in question and expressed overtly through morphological affixes.2 Under this assumption, a lexical category such as adjectives will be analyzed in the same fashion as a functional category such as determiners, as suggested by Koehn (1994); that is, both will match their unspecified agreement features to those of the nominal head. Supporting this distinction between nouns and adjectives is the fact that most nouns in Spanish are specified as either feminine or masculine, but they cannot be both, whereas adjectives can be feminine or masculine according to the noun they are modifying or predicating, for example, bonito (masculine) versus bonita (feminine), as pointed out by Aronoff (1994), Harris (1991), and others.3

In the MP, features such as gender and number are assigned in the lexicon the property of interpretability by Universal Grammar (UG), according to the lexical item they are specifying, for example, gender and number are seen as “interpretable” when assigned to a nominal like casa, but they are seen as “uninterpretable” when they are assigned to a functional category, as with the determiner la. Crucially, interpretability has consequences for the derivation: while interpretable features are allowed to stay through the derivation because their content can be “read” by both the Phonological Form, or PF (roughly speaking, language morphophonological component), and the Logical Form, or LF (roughly speaking, language semantic component) interface levels, uninterpretable features need to be checked or deleted for the derivation to converge because their content is superfluous or cannot be interpreted by the interface levels.

Now we turn the discussion to the derivation of nominal agreement within the MP framework.

1.1.1 Nominal Agreement

The MP derivation starts with a numeration or selection of the LIs, roughly words, that will be used in the derivation, including how many times they will be used. Then the operation of Merge takes place cyclically, until all items from the numeration are used. This operation creates binary relations between two or more items from the numeration. A consequence of Merge then is the creation of new syntactic objects, for example, the DP la casa. Notice in this analysis Noun Phrases (NPs) are interpreted as DPs, as proposed by Abney’s (1987) DP Hypothesis, which take as a complement an NP.4 In this example, the new syntactic object formed, la casa, has a determiner with unspecified/uninterpretable gender and number features, for example, [masculine, singular], and a nominal with specified/interpretable gender and number features, for example, [– masculine, + singular]. Recall that in this analysis, uninterpretable features need to be eliminated for the derivation to converge. This process is known as Agree(ment) (Chomsky 2001), and in this example, it serves to match or add the feature specification values of nominal casa to those of the determiner la. The outcome of Agree is the removal of the uninterpretable features, in this example from the determiner. Once uninterpretable features are valued and deleted, the derivation can proceed to the interface levels.

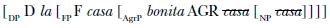

Agreement then in the MP is understood as a feature-checking process expressed syntactically in a Spec-head configuration (with some exceptions) between α (lexical item with interpretable features) and β (lexical item with uninterpretable features), as illustrated in Example 1.1 for the DP la casa bonita.

Example 1.1

In Example 1.1, the nominal head casa raises to the head of the functional projection AgrP to check the agreement features of the adjectival head bonita in a Spec-head configuration.5 In the determiner case, I assume that the agreement features of the N-head are copied (or inherited) by the D-head. Then, the agreement features of the Determiner head are checked by raising the nominal head to the functional category FP, as shown in the example. Notice that in the case of the agreement features of the Determiner head, the checking mechanism does not involve a Spec-head configuration but is checked via percolation, that is, the agreement features of the N-head percolate up from N to D (Radford 1997, among others). For the present monograph, I adopt Cinque’s (1994) and Bosque and Picallo’s (1996) analyses for adjectives and assume that they are generated as specifiers of functional projections, in this case, an Agreement Phrase, as shown in Example 1.1. Furthermore, I assume the availability of a functional projection between the DP and the Nominal Phrase, where Spanish nominals raise to check strong features.6

Notice that N-raising in the example above is motivated within the MP by an additional characteristic of the features, namely, strength. In this framework, a formal feature such as gender or number may or may not be strong, forcing the operation Move (Chomsky 1995). Spanish, among other Romance languages, has been characterized as a language with strong nominal features, hence movement to the appropriate functional head(s) within DP is required for the derivation to converge (Bernstein 1991; Brugè 2002; Cinque 1994; Longobardi 1994; among others). In contrast, languages such as English are presumed to have weak N-features, and therefore no N-movement is required. The notion of feature strength in the MP, although difficult to define in concrete terms, accounts for some cross-linguistic differences between Spanish and English. For example, the attested attributive adjectival placement: in pre-nominal position in English, for example, pretty house, and in post-nominal position in Spanish, for example casa bonita ‘house pretty.’7 That is, in Spanish the noun casa raises to check its strong features, hence appearing before the adjective bonita, whereas in English the noun house does not because it has weak features.8

The overview of agreement within the MP above reveals a puzzling aspect about the agreement process: feature content is added to unspecified constituents and then the same content is deleted later on. Miyagawa (2010) addresses this issue, pointing out the redundant, asymmetric, and apparently irrelevant nature of agreement. For example, in the DP la casa bonita, the relation is asymmetric because only one element, the nominal casa, holds the values for the features that are “copied” to the other elements. Agreement is also redundant because the same information, in this case, the features feminine and singular, is repeated on three constituents: the nominal, the determiner, and the adjective. Furthermore, once the uninterpretable features receive a value specification through agreement, they must be deleted before LF so that they will not receive a semantic interpretation. Therefore, the actual content of agreement seems irrelevant. Miyagawa sheds some light on this matter, proposing that the purpose of Agree is to create functional relations between a functional head and an XP. These relations are critical because they “substantially enhance the expressive power of human language” (Miyagawa 2010, 8). In the example above, the purpose of N-raising or Move is to keep record of the functional relation created in the syntax, that is, agreement, so that it can be used by the semantic interpretation or LF.

1.2 The Initial State

One of the most fundamental questions in the field of language acquisition refers to the definition of the initial state, that is, what do children bring to the acquisition process and how do they converge into their target language in the short span of three to four years, that is, input available to children is comprised of a finite set of sentences but a language is defined of an infinite set of sentences. These questions, part of what is known as the logical problem of language acquisition (Baker & McCarthy 1981; Pinker 1989) have given rise in the literature to a debate that can be defined as the opposition between continuous versus discontinuous approaches, or between nativist versus empiricist views. In this section, I review some of the proposals put forth in the literature and their predictions for the acquisition of nominal agreement, the focus of this monograph.

Pinker (1984) proposes the Continuity Hypothesis, stating that the null hypothesis for an acquisition theory is that the cognitive mechanisms of children and adults are identical, that is, all the various modules of the child’s grammar are present from the beginning of the acquisition process and only require exposure to linguistic data to get activated. Within the Continuity Hypothesis, two major variants have been advanced, namely, Strong continuity versus Weak continuity. Proponents of strong continuity believe that children’s grammar contains all the principles of UG from the onset of acquisition in the form used in the target language (Goodluck 1991; Hyams 1994, 1996, among others). The challenge for this hypothesis is to account for children’s non-adult-like production. Supporters of this view interpret children’s non-target-like utterances or the developmental stages attested in the data as reflections of a deficit in one of the interface levels, that is, the morphophonological or the semantic component. This version of continuity offers a very powerful hypothesis in terms of learnability, that is, children converge to the target grammar in a relatively short period of time because they are not only guided by UG but also select the same options of the grammar in their linguistic community. However, if children’s and adults’ grammars are the same from the onset, this hypothesis needs to posit deficits in other areas to account for children’s less than perfect production, for example, the performance systems. Moreover, it is not clear how children would overcome these issues to converge on the target grammar.

Proponents of weak continuity also believe that children come to the acquisition process guided by UG but that their grammars do not have to conform necessarily to the target grammar; rather, what is relevant is that their grammar does not violate the principles of UG (Crain & Thornton 1998; Crain & Pietroski 2001, among others). In this version, the difference between child and adult grammars is reduced to the differences existing among languages. Notice also that availability of UG helps learners limit the hypotheses generated regarding the linguistic input, that is, UG constrains linguistic variability to a limited number of parameters or different features within the MP. Evidence in support of a continuous approach should show that children have knowledge of UG principles that could not have been derived from the primary linguistic data (Crain & Thornton 1998; Valian 2009a). Experimental studies have brought support for a continuous analysis. For example, research has shown that children do not violate UG linguistic principles, that is, they have knowledge of constraints in interpretation of (Crain & Thornton 1998) and on structure-dependence (Crain & Nakayama 1987). Furthermore, studies have found that children also have knowledge of abstract principles such as the semantic property known as downward entailment (Chierchia 2004; Crain, Gualmini, & Pietroski 2005) that accounts for a series asymmetries in sentences (subject phrase and predicate phrase) with the universal quantifier every, for example, entailment relations among sentences and the interpretation of disjunction (Gualmini, Meroni, & Crain 2003; Meroni, Gualmini, & Crain 2006). Children’s ability to interpret correctly these asymmetries, which on the surface seem unrelated, brings support for the availability of an underlying system guiding the acquisition process. For the present monograph, I assume a weak continuity version of the initial state. This assumption predicts that children’s production of DPs should be the reflection of a language and as such should not violate the principles of UG.

I should point out that several versions of weak continuity have been advanced in the literature to account for the children’s non-adult-like production found in production data. On one hand, some researchers (e.g., Clahsen 1990/1991 and Deprez 1994, among others) assume that functional projections are initially left underspecified in the initial grammar whereas Vainikka (1993/1994) claims that functional projections need to be triggered by the input to be instantiated, hence they develop gradually; that is, children first project Verb Phrase, then Inflectional Phrase, and finally Complementizer Phrase. On the other hand, researchers such as Bloom (1990, 1993) claim that children have performance limitations that affect their production. He argues, for example, that children omit subjects in English due to memory limitations.9

I now turn my discussion to discontinuous analyses of the initial state, that is, proposals defending the hypothesis that children’s grammars are qualitatively different from adults’ grammars. One of the key advocates of this approach is Radford (1990, 1994) in his Maturational Hypothesis. He states that certain principles mature like any instance of biological maturation. In this analysis, children’s early grammar starts at a lexical or pre-categorical stage that lack...