eBook - ePub

Reform, Identity and Narratives of Belonging

The Heraka Movement in Northeast India

- 274 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reform, Identity and Narratives of Belonging

The Heraka Movement in Northeast India

About this book

Reform, Identity and Narratives of Belonging focuses on the Heraka, a religious reform movement, and its impact on the Zeme, a Naga tribe, in the North Cachar Hills of Assam, India. Drawing upon critical studies of 'religion', cultural/ethnic identity, and nationalism, archival research in both India and Britain, and fieldwork in Assam, the book initiates new grounds for understanding the evolving notions of 'reform' and 'identity' in the emergence of a Heraka 'religion'. Arkotong Longkumer argues that 'reform' and 'identity' are dynamically inter-related and linked to the revitalisation and negotiation of both 'tradition' legitimising indigeneity, and 'change' legitimising reform. The results have deepened, yet challenged, not only prevailing views of the Western construction of the category 'religion' but also understandings of how marginalised communities use collective historical imagination to inspire self-identification through the discourse of religion. In conclusion, this book argues for a re-evaluation of the way in which multi-religious traditions interact to reshape identities and belongings.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reform, Identity and Narratives of Belonging by Arkotong Longkumer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Ethnic & Tribal Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

During the early twentieth century, the religious beliefs and practices of the Zeme people of southern Assam in the northeast corner of India evolved and changed in complex ways. Their roots are found in the encounter with the colonial power, Britain, the coming of Christianity and in the emergence of a political consciousness brought about by the changing scenario in the region. The movement known as Heraka embraced new rituals and new ideas of community, tradition and self, as identities and boundaries between people were (re)negotiated. This book examines the evolving project of reform and its intersection with narratives of identity. Before we enter into this discussion, an explanation into the historical backgrounds of the movement is needed.

Although the story of the Heraka has received some scholarly interest, it remains poorly understood. The following discussion seeks to provide new insights into the changing narratives of reform and identity that comprise the Heraka movement. This notion is developed by interrogating ideas of history, tradition and the evolving contextualization of these practices in the Zeme world. In light of this, the book will contribute to the growing literature on indigenous identity, ethnicity, nationalism and the importance of religious boundaries with regard to Northeast India and more broadly in the South Asian and Southeast Asian contexts.

Heraka

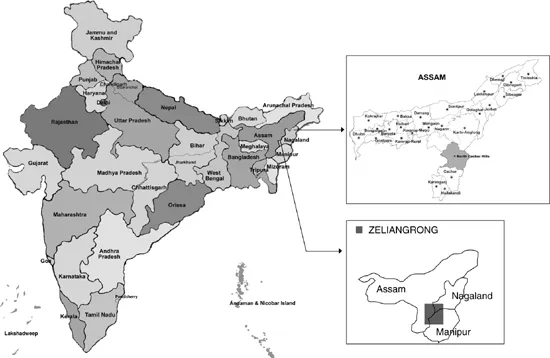

Heraka is a religious reform movement derived from the ancestral practice known as Paupaise.1 It was taken up by the Zeme, among other Naga communities, during the period of British colonialism in Northeast India (see Map 1.1). From early descriptions of events in 1929 and over the next 45 years, Heraka has been known by various names, for example, Kacha Naga movement, Gaidinliu movement, Periese (old practice), Kelumse (prayer practice) and Ranise (‘practice of the queen’, a reference to Gaidinliu as people’s queen), and sometimes pejoratively as Khampai,2 all representing a different point in the development of the movement which finally came to be known as Heraka in 1974.3 In this book, I have generally used ‘Heraka’ as shorthand to indicate all these stages. My analysis of the Heraka reform movement is primarily among the Zeme of North Cachar Hills, Assam.

Among the Heraka, there are two important figures who are seen as prophets, leaders and reformers. Jadonang (1905–31) and Gaidinliu (1915–93) are from the Tamenglong district of Manipur and are both Rongmei Nagas (see below). Due to their alleged threat to the British and their hatred of the Kukis, a neighbouring tribe in Manipur, Jadonang and Gaidinliu were accused of stirring up trouble. The British eventually hanged Jadonang in 1931 for alleged murder and human sacrifice, while Gaidinliu escaped to North Cachar Hills. Although Jadonang is often viewed as initiating the reform, for the Heraka it is Gaidinliu who is held in more esteem. The British captured Gaidinliu in 1932 after which she spent 18 years in prison. During this time Jawaharlal Nehru heard of her exploits and named her ‘Ranee’ (queen). Therefore, Gaidinliu is also known as Rani Gaidinliu, and Ranima (queen mother). Throughout the book, I use the names ‘Ranima’ and ‘Gaidinliu’ interchangeably; but the Zeme, above all, call her Ranima, as it indicates their more intimate connection with her.

The Zeme Nagas

The Zeme (also spelt Jeme, Nzemi, Zemi, Zemei) comes from the word zemena (human). To be human, they say, is to be Zeme. They are also known by their ‘kin’, that is the related communities, Rongmei (also spelt Rongme, Rongmai) and Liangmai (also spelt Liangme, Liangmei), as Zena or Nzie (frontier or periphery). The Zeme were supposedly the frontier people who moved on from their ancestral home Makuilongdi, in present-day Manipur (Kamei 2004: 36). During colonial times, they were also known as Kacha Nagas (along with the Liangmai and Rongmei), while in Manipur the Rongmei were known as Kabui Naga (Hutton 1969: 352).

It is said that before coming to Makuilongdi, the ‘Nagas’ gathered at a place called Makhel (a place believed to be near the Chindwin river in Myanmar). The people lived amicably and harmoniously with one another there. When they decided to disperse, they gathered around a wild apple tree at Charaho (miracle ridge) and took an oath, pledging that they would come together again and live as a kingdom. To keep this dream alive and the identity of the tribe intact, they proclaimed a genna (prohibition) to be observed every time a branch of the tree is broken. As recently as 1950, it is said, this tradition was maintained by the Angami, Sema, Rengma, Lotha, Zeme, Liangmai, Rongmei and Sepoumaramth people (Pamei 2001: 6). The Zeme, Liangmai and Rongmei people left the area and went in search of land until they came to Makuilongdi.

The population grew in Makuilongdi and the village expanded and grew to exactly 7,777 houses. They decided that in order to maintain a healthy habitat they needed to spread out and find fresh pastures. The 3 brothers, who represented the Zeme, Rongmei and Liangmai decided to split up. The oldest, Liangmai, decided to stay in the area. The Zeme spread out further west towards the Barak river (present-day North Cachar Hills and Peren district of Nagaland) while the Rongmei migrated far to the south (to present-day Manipur and Cachar) (Pamei 2001: 16–17). These narratives create strong bonds even today by helping people recreate strong unifying identities linking back to particular points in time. By establishing a collective memory they are able to envision a community built on shared history and culture. This brings us to the adoption of the term ‘Zeliangrong’ (see Map 1.1).4

Gangmumei Kabui (also Kamei), the famous Rongmei historian, mentions that the word Zeliangrong was coined in 1947, and that it is a combination of the three prefixes of these ‘tribes’: Zeme, Liangme and Rongme (Ze-liangrong). Further, he says,

Though chronologically the name was coined in 1947, a faint notion of their common ancestry was contained in their legends and the idea of inter-tribal solidarity and unity was implanted by Jadonang and Gaidinliu during their uprisings (1930–32). (1982: 53)

The purpose for such a union was to emphasize the need for a collective front with the objective of achieving the ‘economic, social, educational and political advancement’ of the Zeliangrong people (Kamei 2004: 176). Due to British classification and the imposition of separate administrative units in three regions, North Cachar Hills, Naga Hills and Manipur, the Zeliangrong people remained separated. It is said that the Jadonang and Gaidinliu movement attempted to unite the three groups into a common front to fight the British invaders by participating in a common tradition that unified their practices. The reform movement, Heraka, was the product and emblem of this unification. However, this has created certain problems as the term Zeliangrong is a continually (re)constructed and contested enterprise. Gangmumei Kabui emphasizes the problem. He says,

MAP 1.1 India and Assam

A very interesting feature of the [Zeliangrong] movement, which is very flexible, is the absorption of small tribes into the fold of Zeliangrong. For example, one Chothe village of Bishenpur was declared to be absorbed into Zeliangrong. Wainem, originally consisting of immigrants from Tripura, is now converted into Zeliangrong. The inclusion of these tribes has raised the question whether such a composite name like Zeliangrong could cover all of them. For example, Puimei, a sub-tribe of the Rongmeis, have been demanding for some years that their name should be included in Zeliangrong nomenclature. (Kabui 1982: 62)

For this reason Rani Gaidinliu supposedly preferred the word ‘Haomei’, which means ‘ourselves’ to Zeliangrong.5 A statement attributed to Rani Gaidinliu asserts,

Rani Gaidinliu feels that it will be better to remove the name Zeliangrong and adopt the original name of ‘Haomei’ as the name and goal of the movement. She thinks that Haomei will cover all seven groups [Zeme, Liangmei, Rongmei and Maram, Mpumei, Kourang, Wainem and Toite], big and small, with similar traditions and will not encourage the separatist tendencies of the bigger sections of her people. (Mukherjee et al. 1982: 78)6

Rani Gaidinliu had already envisaged a mixed ethnic group signalled by the adoption of the word ‘Haomai [or Haomei]’. This category can incorporate those on the fringes, and is necessitated by the common practice of intermarriage between various people. The marriages between these groups create a problem in the fluidity of categories because it means going outside the group, challenging the purity of the group. Indeed, ‘ourselves’ is a more inclusive concept, providing infinite probabilities in terms of people’s belonging, rather than limiting the category as a term like Zeliangrong does; the former encompasses the fluidity of categories while the latter restricts them. However, ‘Haomei’ is not used now. It is tempting to speculate that Zeliangrong as a fixed identity is more prestigious due to its political profile, ‘Haomei’ seeming less prestigious. The ethnic construction of the word Zeliangrong is vital to their discourse (e.g. the recent book, The Trail from Makuilongdi), suggesting something unique and historical. These attempts to trace their origins have signalled a new revival within Zeliangrong society.

Nagas and the British

The Zeme are included in the category ‘Naga’. Some say the word ‘Naga’ comes from the Bengali word Nangta, in Hindi ‘Nanga’ (naked). Others think that the Kachari word Naga (a young man) supplies the name, while others again derive it from ‘Nag’ (a snake). Colonel Woodthorpe, who worked in the Naga Hills in the late nineteenth century, notes that ‘not one of these derivations is satisfactory, nor does it really concern us much to know more about it, seeing that the name is quite foreign to and unrecognized by the Nagas themselves’ (1969: 47). This ambiguity remains unresolved at the descriptive level. On the level of representation, it is also still vague. There are now some 68 Naga tribes recorded both in India and Myanmar (Nuh 2006: 24–6), compared to only 9 recorded in the 1891 Assam Census. The word ‘tribe’, with its vague terrain of representation, is replete with conceptual problems. However, it is still a valid usage in India due to the protective discrimination accorded to those listed in the Schedule of Tribes (article 342 of the Indian constitution). The word ‘tribe’ is used here in conformity with the ‘schedule list’. The word ‘indigenous’ is now being used in some Naga nationalist literature as part of the language of ‘self-determination’. However, it is not used widely (see also Beteille 1998).

This large increase in the number of Naga tribes between 1891 and 2006 is due to expanding identities in the post-colonial situation: unlike earlier notions of fuzzy belongings, new identities now increasingly delineate ‘those who belong from those who do not’ (Karlsson 2000: 258). Identities in this sense are not invented randomly, implying a sort of ‘constructionism’; they result from an ongoing process that occurs on many levels. Sometimes identities are labile to the extent that they are used for upward mobility; at other times identity projects commonality and purpose as a form of resistance against a dominant force; while sometimes its practicality is questioned. Jamie Saul, in his magnum opus The Naga of Burma, offers us his insights regarding some of the above points. He points to the fact that the term ‘Naga’, in use in the Assam region for some time, was simply adopted by the British based on loose linguistic and cultural associations, in order to separate the people into ‘tribes’ (Saul 2005: 17). This has created a ‘political identity’ for the Nagas in a two-way process: those who want in and those who want out. In the first case, some small groups like the ‘Old Kuki’ are absorbed into the Naga fold to increase their political profile. Others, like the Maring, though linguistically classified as Naga, are not sure if they want to be associated with the Nagas. They cite their cultural difference in terms of their social structure, architecture and personal appearances, which more closely resembles that of the Chin group of the south. Their absorption into the Naga fold, they say, would have ‘little practical bearing’ (2005: 17–19). In this way, ‘Naga’ identity is not a fixed entity that requires its members to stand by it unquestionably, but a shifting and, to some extent, voluntary concept.7

The same can be said of what ‘Zeliangrong’ means to those in it and those who want to be in it. The association of Heraka with the Zeliangrong identity is a contested matter. Most Heraka claim that Heraka and Zeliangrong are inextricably linked: to be Heraka is to be Zeliangrong. In other words, the Heraka was envisioned as uniting the Zeliangrong by giving the latter an aura of credibility and overall unity associated with the reform: the Heraka reform is for the Zeliangrong people. But due to the large presence of Christians among the Zeliangrong, the nature of Heraka as representing the larger sentiments of the people is contested. Moreover, the Heraka population is popular among the Zeme and Liangmai (together known as Zeliang in Nagaland) rather than Rongmei. Some Rongmei in recent years have also adopted reforms attributed to Jadonang, while the Heraka look up to Ranima as their preceptor. As will become clear in Chapter 2, these notions are pivotal in understanding the Zeliangrong as an evolving entity, as Gangmumei Kabui also mentioned earlier. In this book, I have maintained the word Zeliangrong as it appears in most primary texts and scholarly works. The Heraka also use the term Zeliangrong Heraka Association for the larger group from Assam, Nagaland and Manipur. My own usage is to distinguish ‘Zeme Heraka’ from the wider ‘Zeliangrong Heraka’ (this is not a distinction drawn by the Heraka themselves). Therefore, as the Zeme Heraka themselves do, I use Zeliangrong only when I mean Zeliangrong, referring to the group as a whole.

What is in a Name?

During my first week of fieldwork in North Cachar Hills district, I went around asking the Zeme people the question ‘what is Heraka?’ Many could not give me a straightforward answer; others would ponder and arrive at a conclusion. It was not because of their ignorance or for that matter their lack of interest that they failed to arrive at some answer, it was simply that they were not in a habit of explaining terminology that mattered to a researcher like me. ‘Is there a right or wrong answer’, they would often ask, or better still ‘go ask the leaders, they are the ones you should be talking to’. Even when I did manage to speak to the leaders, their response would often be the official – perhaps rehearsed – response, ‘Heraka means “not impure”’. I soon realized that this definition is used in much of the wider Heraka literature to portray an image of the Heraka as practising the ‘pure’ indigenous tradition of the Zeme. In the introduction to the Zeliangrong Heraka Preacher Handbook, N. C. Zeliang, the past-President of the Zeliangrong Heraka Association, says, ‘Heraka literally means, in Zemei “PURE”. The Heraka religion is a pure or reformed religion of the Zeliangrong people comprising three kindred tribes, the Zemei, Liangmai and Rongmei’ (1998: 3). What N. C. Zeliang refers to is attributed to the Heraka’s adoption of one God, Tingwang, and the subsequent ban on animal sacrifices. Thus, the purity is a metaphor for no blood sacrifices and the adoption of a single God (this will be explored in Chapter 4).

For a while, I worked under the assumption that Heraka did mean ‘not impure’. It was only later, when I visited the villages, that another explanation was offered to me for the origin of the word Heraka and its meaning. I was told that:

Ka is to fence, to obstruct, to avoid, to give up – all these words can be used in different contexts. ‘Hera’ means ‘small gods’. So all these neube [prohibitions] and sacrifices associated with the smaller gods must be fenced out, avoided, and only Tingwang must be worshipped. This is the meaning of Heraka.

The two definitions provide us with the way Heraka reform is envisaged. The latter definition is more concerned with the actions that attempted to reform traditional practices of appeasing gods by sacrifices. By fencing themselves in, by their obeisance to one God, Tingwang, any threat is averted from the smaller gods. One must understand the intense anxiety associated with the smaller gods, which was deeply embedded in people’s consciousness. On the other hand, the image of the fence that is protective retains much of traditional understanding of purity and danger associated with any period of ritual (this will be analysed in Chapter 4). In this way, by giving up these gods, and the associated blood sacrifices, the Heraka are able to envisage a pure state, protected by the fence.

Just what this means is explained by Pautanzan Newme, the General Secretary of the Heraka Association, in his article ‘The Origin and Reformation of Heraka Religion’ (2002),8 published in the local Silver Jubilee Souvenir Magazine, a journal which often highlights Heraka operational achievements and ideological view points. It also acts as an official document that publicizes the Heraka agenda to the masses and measures their ‘progress’ as a movement. Pautanzan Newme says,

The 1st phase of teaching: Ranima told them to offer sacrifices to one God, Tingwang. In this phase blood sacrifice was permitted.

The 2nd phase of teaching: This was introduced after 15 years. Ranima advised them: while performing ‘puja’ to cut with a dao [hacking knife] if it was a big animal, and to use a piece of stick (nkiadang) with smaller animals (like hen or cockerel) while holding the legs and let blood shed. At this phase, the ‘sacrificial ceremony was a bit diminished than the first phase’.

The 3rd phase of teaching: In this stage, introduced after a further 10 years, Ranima instructed her followers that one should ‘perform puja with the animal tied and its mouth stuffed with a rag and killed. But a chicken must be killed with the hand, by twisting the neck, without oozing any blood’. In this phase, the sacrifice of animals is further diminished.

The 4th phase of teaching: After another 5 years the 4th phase was introduced. On the 11th of January 1990, at Kepelo village, North Cachar Hills, ‘the preceptress (Ranima) vigorously declared and confessed before the general public that we have fully done the requirement of sacrificial oblation in puja. Now, influential sacrifices of animals in any puja are to be totally abolished. And we are free to perform puja with a clean mind and body at any specific time and day.’ Ranima proclaimed to the people,

while performing puja with a clean mind and body, recite the Holy psalms and sing the prayer songs; you would be blessed for sound health and to live a very happy life free from evil spirits. And if anything [is] wrong with you, you may throw it upon me – I can affirmably bear such things for your sake. (P. Newme 2002: 4)

The writer further declar...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Circling the Altar Stone: Bhuban Cave and the Symbolism of Religious Traditions

- Chapter 3 Millenarianism and Refashioning the Social Fabric

- Chapter 4 Changing Cosmology and the Process of Reform

- Chapter 5 Negotiating Boundaries

- Chapter 6 Community Imaginings and the Ideal of Heguangram

- Chapter 7 Conclusion

- Notes

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index