![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction:

Materials, the roles of teachers and learners, and teacher education

. . . far too many institutions seem to view materials and equipment as being more important than students and/or teachers. . . . We are, after all, teaching students – not materials.

(Edwards, 2010: 73)

As teacher preparation increases, the importance of the textbook diminishes.

(McElroy, 1934: 5)

1. Introduction

The Preface highlighted the importance of materials in language teaching and the need to gain a better understanding of how teachers select and use materials. It also hinted at a key role for teacher education. The three sections of this chapter reintroduce each of these themes. Section 2 takes a closer look at what we mean by ‘materials’, the arguments for textbooks and criticisms of textbooks; Section 3 examines teachers’ roles in relation to materials and learners; and Section 4 deals with teacher education.

2. Materials

2.1 What do we mean by ‘materials’?

If you ask 100 English language teachers who are teaching learners of different ages, with different needs and in different contexts what materials they use in their teaching their individual answers will vary considerably. Some lists may contain only one item; others will be much more extensive. Certain items will appear in most lists; others may be much less frequent. The master list, containing all the items from the individual lists, will almost certainly include:

•A textbook, produced by a commercial publisher (i.e. for profit), a Ministry of Education or a large institution (e.g. university language centre, private language school chain); this will normally be accompanied by some combination of the following: teachers’ notes, a student workbook, tests, visual aids (e.g. wallcharts, flashcards), a reader, audio and video material / computer-based (CALL) exercise material / Smartboard software / web-based materials.

•Commercial materials that are not provided as part of the textbook package: for example, reference material (dictionaries, grammar books, irregular verb charts) and practice material (supplementary skills books, readers).

•Teacher-prepared materials, selected by or devised by the teacher or a group of teachers working together:

–authentic print materials (e.g. newspaper and magazine articles, literary extracts, advertisements, menus, diagrams and other print materials downloaded from the internet which were not designed for language teaching)

–authentic recordings (e.g. songs, off-air recordings, recordings of academic lectures; Internet sources such as YouTube)

–worksheets, quizzes and tests downloaded from the internet or photocopied from other sources

–teacher-developed materials (e.g. oral or written activities developed to accompany authentic or textbook materials, self-standing tasks and exercises, tests, overhead projector transparencies, PowerPoint presentations, CALL materials)

–games (board games, Bingo, etc.)

–realia (real objects, including classroom items) and representations (photos, drawings, including drawing on the board).

Some teachers will also enlist the aid of learners to supply or create materials. Indeed, we might broaden the notion of materials to include all use of the target language by learners and the teacher in that this is a potential input to learning, especially when it is captured by a recording or takes a written form. If we stretch the notion of materials still further, we might also add any other visual or auditory means (e.g. facial expression, gesture, mime, demonstration, sounds) used by the teacher or learners to convey meaning or stimulate language use. Tomlinson (2001) takes this kind of broad view of materials, defining them as ‘anything which can be used to facilitate the learning of a language. They can be linguistic, visual, auditory or kinaesthetic, and they can be presented in print, through live performance or display, or on cassette, CD-ROM, DVD or the internet’ (p.66).

2.2 Some distinctions

The list above has been organized in such a way that certain distinctions are immediately apparent: between, for example, textbook packages, other (supplementary) commercial materials and materials prepared by teachers themselves; between reference material and practice material; and between various types of teacher-prepared materials. McGrath (2002: 7), writing specifically about text materials, differentiates between four categories of material:

We might also wish to distinguish on the basis of where materials were produced (‘global’ vs ‘local’ textbooks), their intended audience (General English – sometimes dubbed Teaching English for No Obvious Reason (TENOR) – or English for Specific Purposes (ESP)) or their linguistic focus (on a language system such as grammar or phonology, or a language skill such as listening or speaking).

However, there are other distinctions which are perhaps more important because they concern the roles that materials play: that between non-verbal and verbal materials, for instance, that between materials-as-content and materials-as-language, and the four-way distinction made by Tomlinson (2001) between materials which are ‘instructional in that they inform learners about the language, . . . experiential in that they provide exposure to the language in use, . . . elicitative in that they stimulate language use, or . . . exploratory in that they facilitate discoveries about language use’ (p.66, emphases added).

Non-verbal materials such as representations can help to establish direct associations between words and objects and clarify meanings; they can also be used to stimulate learners to produce language, spoken and written. However, for language learning purposes they are much more limited than verbal (or text) materials: spoken language in the form of classroom talk or recordings, materials containing written language and multimedia materials (literally, anything combining more than one medium). The form in which ideas are expressed in these materials may serve as examples of language use – and, indeed, of discourse structure; this language also carries content, ideas to which learners may react and from which they may learn.

The importance of materials-as-content should not be underestimated. One of the beliefs which links the communicative approach to methods of a century and more earlier, such as the Direct Method, is that learning to speak a language is a natural capacity which is stimulated by three conditions: ‘someone to talk to, something to talk about, and a desire to understand and make yourself understood’ (Howatt, 2004: 210, emphasis added). In language classrooms, that ‘something to talk about’ may be a subject selected by the teacher or initiated by a learner, including some aspect of the language itself, or it may be a topic, text or task in the materials. In language learning terms, what matters is that it should trigger in learners the ‘desire’ to understand and make themselves understood. The implication is clear: the more engaging the content, the more likely it is to stimulate communicative interaction. Learning thus takes place through exposure and use – or in Tomlinson’s (2001) terms – through experiencing the language or responding to elicitation. Content selected for its relevance to learners’ academic or occupational needs can, of course, also fulfil broader learning purposes, and content and language integrated learning (CLIL) has aroused much interest in recent years.

In reference materials such as dictionaries and grammar books, language is the content; and explicit information about the language, plus exercises, also forms the bulk of student workbooks and some textbooks. Tomlinson refers to this as the ‘instructional’ role of materials. Helpful though this approach to the language may be for analytically inclined learners, it needs to be complemented by text-level examples of language in use. These texts, spoken and written, together with all instructions and examples, must illustrate language which is accurate, up-to-date and natural. They can then serve both as language samples in which rules of use can be ‘discovered’ by learners – Tomlinson’s ‘exploratory’ role for materials – and as a model for learners’ own production. We might describe this way of looking at materials as a materials-as-language (rather than materials-as-content) perspective.

2.3 Coursebooks and their advantages

As far as language learning is concerned, then, the importance of materials-as-content lies primarily in their value as a stimulus for communicative interaction, and of materials-as-language as the provision of information about the target language and carefully selected examples of use. The modern textbook, now normally referred to as a ‘coursebook’ because it tends to be used as the foundation for a course, is designed to combine these functions.

It is easy to understand why coursebooks are so popular. Their advantages include the following:

1They reduce the time needed for lesson preparation. Teachers who are teaching full-time find coursebooks invaluable because they do not have enough time to create original lessons for every class.

2They provide a visible, coherent programme of work. Teachers may lack the time and expertise to design a coherent programme of work. The coursebook writer not only selects and organizes language content but also provides the means by which this can be taught and learned: ‘the most fundamental task for the professional writer is bringing together coherently the theory, practice, activities, explanations, text, visuals, content, formats, and all other elements that contribute to the finished product’ (Byrd, 1995b: 8). Coursebooks are also reassuring for the parents of younger learners who are keen to know what their children are doing and to offer their help if it is needed.

3They provide support. For teachers who are untrained or inexperienced, textbooks (and the Teacher’s Books that normally accompany them) provide methodological support. Those who lack confidence in their own language proficiency can draw on linguistically accurate input and examples of language use (Richards, 2001b). At times of curriculum change, coursebooks offer concrete support for the inexperienced and experienced alike (Hutchinson & Torres, 1994).

4They are a convenient resource for learners. The visible coherence – or sense of purpose and direction – referred to above is also helpful for learners. Because coursebooks enable a learner to preview or review what is done in class, they can promote ‘feelings of both progress and security’ (Harmer, 2001: 7). In short, they provide a framework for learning as well as for teaching – ‘A learner without a coursebook is more teacher-dependent’ (Ur, 1996: 184). Compared to handouts, coursebooks are also more convenient.

5They make standardized instruction possible. If learners do the same things, at more or less the same rate, and are tested on the same material (Richards, 2001b), it is easy to keep track of what is done and compare performance across classes. From this perspective, coursebooks are thus a convenient administrative tool.

6They are visually appealing, cultural artefacts. The attraction for learners of the modern global coursebook lies in no small part in its visual appeal – the use of colour, photographs, cartoons, magazine-style formats. Cultural information is conveyed by these means as well as through the words on the page (Harmer, 2001).

7Coursebook packages contain ‘a wealth of extra material’ (Harmer, 2001: 7). Beyond the student book, the modern coursebook package makes available a range of additional resources for both classroom use and self-access purposes.

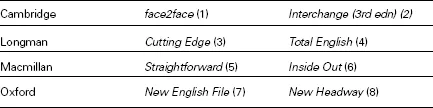

This last point is graphically illustrated in McGrath’s (2007) analysis of eight global coursebook packages (see Table 1.1). The materials surveyed were as follows:

As McGrath (2007: 347–8) notes, one feature of such packages is that they provide integrated resources for teachers. For example, Teacher’s Books (or resource packs) may now contain photocopiable activities, supplementary materials offering ‘extra support/challenge’ for mixed groups and warm-up activities (New English File), and further resources for teachers include:

•Teacher’s Video Guide (Inside Out contains guidance and worksheets)

•customizable texts (face2face)

Table 1.1 Content of coursebook packages

•customizable tests on CD (Inside Out)

•publishers’ websites linked to specific courses (Oxford sites include articles, downloadable worksheets and activities, and discussion groups)

•publishers’ websites available to any teachers (e.g. Macmillan’s onestopenglish.com).

Additional materials for learners are also provided – for example:

•a CD-ROM to accompany the student’s book (face2face) or workbook (that for New English File includes video extracts and activities, interactive grammar quizzes, vocabulary banks, pronunciation charts and listen and practise audio material; the workbook for Inside Out comes with either an audio cassette or an audio CD)

•publishers’ websites for students linked to specific courses (e.g. New English File)

•publishers’ websites available to any learner.

Linked resources which can be used in combination with specific courses are also available. These include specially designed supplementary materials and stand-alone resources. Examples include:

•business Resource Books (New English File)

•pronunciation course; interactive practice material on CD-ROM (Headway)

•bilingual (Dutch/French/German) ‘Companions’ containing listing of words/phrases with pronunciation, translation and contextualization (Inside Out).

Such developments are impressive: ‘25 years ago, who would have dreamed of website resources linked to courses or freely available general website resources for teachers and learners? And more is being offered almost daily. For instance, whiteboard software is available to accompany the two Cambridge titles, and learners can register for free e-lessons with Macmillan’ (McGrath, 2007: 348). At the time of writing, e-books and e-readers have begun to have an impact on ELT publishing. Macmillan’s Dynamic-Books software will reportedly allow teachers to edit e-book editions of Macmillan coursebooks in order to tailor them to the needs of their students (Salusbury, 2010). In a few years’ time, other innovations will no doubt have been introduced.

2.4 Doubting voices

Given these potential benefits, it is hardly surprising that, despite occasional warnings of the demise of printed coursebooks in the face of technological development, coursebooks continue to be published and, particularly in contexts where English is taught as a foreign language by non-native English speaking teachers (NNESTs), ‘wh...