- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Origins of the Civilization of Angkor

About this book

The Origins of the Civilization of Angkor reflects the results of a research programme conducted by Charles Higham over the last twenty years, highlighting much entirely new, and occasionally surprising, information and providing a distinct perspective on cultural change over two millennia. The book covers the background of environmental change, the adoption of rice farming, archaeogenetics, the adoption of copper-based metallurgy, the iron age and the origins of state formation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Origins of the Civilization of Angkor by Charles Higham, Richard Hodges in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Debates

Towards the end of the sixteenth century, Portuguese missionaries began to explore the forested interior of Cambodia. It was here, that they encountered the abandoned complex known today as Angkor (Groslier 2005). Although some of the temples were still centres of Buddhist worship, most had been left to the encroaching jungle 150 years previously, when the court moved eastward to the vicinity of the modern capital, Phnom Penh. What they witnessed is best described in their own words. Antonio da Magdalena explored the ruins in 1586. ‘The city’, as he described it to the archivist Diogo do Couto, ‘is square, with four principal gates, and a fifth, which serves the royal palace . . . the gates of each entrance are magnificently sculpted, so perfect, that they looked as if they were made from one stone’. He then commented on the fact that the stones had to be hauled to the city from a distance of 20 leagues, a feat that demanded a large and organized labour force. He then turned to the temple mausoleum of Angkor Wat, concluding that ‘it is of such extraordinary construction that it is not possible to describe it with a pen, particularly since it is like no other building in the world. It has towers and decoration and all the refinements which human genius can conceive of’.

It was only a matter of years before we can read of the first speculation as to who might have been responsible for this abandoned city. In 1601, Marcello de Ribandeyra (1601) suggested that it was built by Alexander the Great, or the Romans. Forty-six years later, it was proposed that it was the work of the Roman Emperor Trajan.

The civilization of Angkor

The civilization with its capital at Angkor was one of several that flourished in Southeast Asia before the first European contact (Higham 2001). Angkor dominated the lowlands of Cambodia, and reached into adjacent parts of Thailand and Vietnam. In the former area, it bordered the civilization known as Dvaravati, which spread over the broad floodplain of the Chao Phraya River in Central Thailand, while the Cham kings ruled in the coastal plains of Central Vietnam. Debates on their origins have always incorporated one common theme: they display in their architecture, religion and language, pervasive influence from the civilizations of India. When translated, the inscriptions set up by Angkorian kings and grandees were found to be inscribed in Sanskrit as well as an archaic form of Khmer, the indigenous language of Cambodia. Sanskrit is the priestly language of the Hindu religion. Many Sanskrit words continue to be incorporated into Thai and Khmer. Thus the Thai province Chaiyaphum means victorious land. Simon de la Loubère was a French diplomat who visited the court of King Narai of Ayutthaya in Thailand in 1687. He noted that the language included words and expressions in Pali, another Indian language closely associated with Buddhism (Loubère 1693).

Many of the religious monuments of Angkor portray Hindu gods, such as Shiva and Vishnu, others are embellished with statues of the Buddha. The temples of Champa were usually dedicated to Shiva, while in Thailand, Buddhism was adopted by the rulers of Dvaravati. The temples themselves were often constructed, as in India, in brick, and the building designs owed much to Indian inspiration.

These facts gave rise to a simple explanation of origins, known as the process of Indianization. Expressed by the leading scholars of the day, it was formulated when serious archaeological research had barely begun, and our knowledge of the prehistoric inhabitants of Southeast Asia was in its infancy. A. Foucher (1922) proposed that Indian immigrants encountered ‘savage populations of naked men’. Ramesh Majumdar (1944) wrote of Indian colonies in Southeast Asia, the only possible explanation for the saturation there of Indian customs and language. The Russian Leonid Sedov (1978) concluded that Indians ‘acquainted the aborigines with various new techniques including methods of land reclamation, with handicrafts and the art of war’. George Cœdès was the doyen of Angkorian scholars, responsible for the translation of every known inscription from Sanskrit into French, and a man of unrivalled knowledge of the early states of Southeast Asia. In 1968 he wrote that Indianization involved a steady flow of immigrants who founded Indian kingdoms to a people ‘still in the midst of late Neolithic civilization’ (Cœdès 1968).

Cœdès and his French colleagues came to Southeast Asia in the wake of French colonial expansion into what are now Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, and seeing the state of Angkor and its contemporaries as the result of a previous wave of colonization came easily to them. The decade of the 1960s, however, was a major turning point. By then, the French Eastern Empire was no more. Prehistorians were beginning to explore what had been widely regarded as a cultural backwater, and began to piece together what actually happened during the centuries before the foundation of local kingdoms. These findings in their turn, generated their own debates, particularly over chronology and the nature and the pace of cultural changes during the long duration of prehistory. Moreover, a new generation of historians began to explore the written records of Angkor, Champa and Dvaravati more deeply. Where Cœdès concentrated on the Sanskrit texts to reconstruct royal genealogies, Vickery (1998) incorporated the old Khmer record to peel off the veneer of Indianization and reveal a deep legacy of indigenous gods, names and customs.

Four debates

The rulers of Southeast Asian kingdoms were sustained by the surpluses generated by those who toiled in the heat of the day to cultivate rice. Without rice, it is hard to envisage how the court societies, with their ostentatious temples, bureaucrats, scribes, architects and craft specialists could have been. Rice is a remarkable plant. It is essentially a marsh grass, that can flourish even on poor soils with no fallow season, provided that there is sufficient rainfall. It is therefore inevitable, that the first debate to be considered is why and how, after at least 50,000 years of hunting and gathering in the heat of Southeast Asia, should some communities begin to cultivate rice, and herd domestic animals. Let us contrast this situation with what happened to the southeast, in Australia. Both areas were occupied by anatomically modern humans who left their African homeland by 60,000 years ago. By following a line of least resistance, the warm coastal tracts of India and Southeast Asia, these hunter-gatherers ultimately crossed by boat into Australia. In the fullness of time, agriculture and stock raising were adopted on the Asian mainland, to be followed by the foundation of early states. But in Australia, hunting and gathering continued down to and beyond the period of European settlement. Who was responsible for this transition to farming, the so-called Neolithic Revolution? When did it take place, and what was its impact on human behaviour?

The second debate revolves round the timing and the impact of metallurgy. In Southeast Asia, this involved the smelting of copper and tin ores, and mixing the metals together to form bronze. Although the presence of a discrete Bronze Age was first identified in the 1870s when the Cambodian site of Samrong Sen was excavated (Mansuy 1902), the excavations at two sites in Northeast Thailand a century later generated a blaze of controversy when it was claimed that the prehistoric inhabitants of Non Nok Tha and Ban Chiang were responsible for the earliest bronzes in the world (Solheim 1968, Gorman and Charoenwongsa 1975). Widespread interest among archaeologists reflected the significance of metallurgy as a catalyst for cultural change. Essentially, bronzes by their very nature called on a high degree of labour to secure the raw materials, and expertise to alloy and cast the molten metal. The ownership of bronze weapons and ornaments was a ready means to advertise social standing and prestige. The greater their rarity, the more desirable bronzes would become. In the Near East, the Indus Valley and in China, it is possible to link the rise of social elites with increasingly elaborate bronzes. But in Southeast Asia until very recently, no such development has been identified. This particular debate therefore, revolves round identifying when metallurgy was adopted, where the knowledge came from, and its actual impact on the lives of those who were involved.

If bronze had transformational potential for human societies, iron had even more. Iron ore in Southeast Asia is more widely available than the ores of copper or tin, but it also requires greater heat to extract metal. Once achieved however, the smiths forged ornaments, weapons and tools used in manufacturing or agriculture. So we turn to a further debate: when did iron become part of the technological repertoire of prehistoric people in Southeast Asia, and how can we measure its impact on social change?

The last debate is the most complex, for it involves one of the most significant developments in the history of our species: the origins of civilization. Archaeologists can recognize an extinct civilization through its hardware in the form of large and impressive buildings, often concentrated into what we term a city. Such buildings in effect represent frozen energy, and reflect an intensive organization of labour. The hardware often includes massive tombs and temples, representing both the status of the ruling elite, and the ideology that sustained them. Recording events, payments, predictions for the future, claims to special powers through a system of writing are also widespread in early states. It is from such evidence that we can also attempt to isolate and understand the software in the transition to the state. How does an elite, representing a tiny fraction of the population, come to hold sway over the majority? Under what sanctions, or circumstances, do those who toil in the rice fields give up a surplus of what they produce to sustain their rulers? Can we identify any changing circumstances that could have encouraged the formation of a ruling dynasty able to occupy a palace, hold sway over a large population of followers and appropriate to itself wealth and exceptional status? Such circumstances might have involved, for example, a growing population, the need to respond to external military pressure, the possibility of controlling new trading opportunities or ownership of a vital resource, such as salt, or iron ore. In Southeast Asia, there is no final resolution to this fascinating question, but we are much closer to understanding what happened than when it was assumed that the arrival of sophisticated Indian colonists tutored a simple indigenous population into the arts of a civilized life.

2

Southeast Asia in 2000 BC

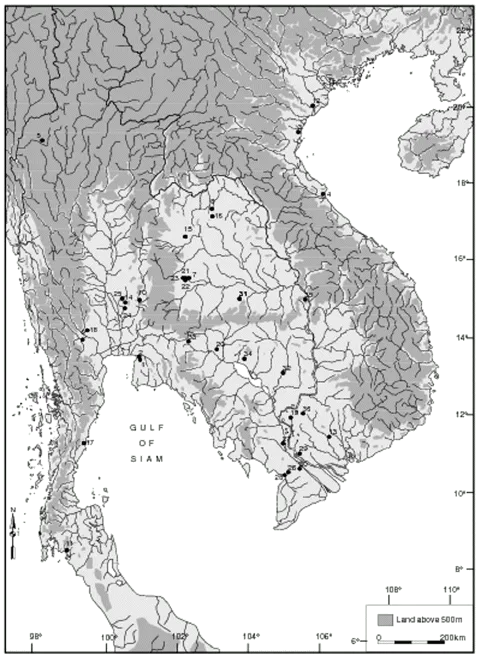

Four thousand years ago, those living in Southeast Asia (Figure 2.1) inherited a land drastically changed from that of their ancestors over the previous ten millennia, and their descendants were to experience just as profound changes, but of a different kind. With the end of the last ice age, about 12,000 years ago, the sea level progressively rose by at least 120 metres. In Southeast Asia, this resulted in the loss of land the size of India, and the creation of many islands which had formerly been relatively high ground. By 2000 BC, the sea actually rose about 2 metres higher than its present level, and formed a new shoreline that is now stranded, many kilometres inland. The area lost to the sea, known as Sundaland, would have been home to many groups of hunter-gatherers whose ancestors, Anatomically Modern Humans, had spread into Southeast Asia and beyond in Australia at least 50,000 years ago from their African homeland. Over this vast expanse of time, these hunter-gatherers adapted to a range of different environments. Naturally, nothing is known of those who lived where the sea has now encroached, but we can illuminate the rhythm of life of their descendants, who lived along the old, raised shorelines.

One such site is known as Nong Nor. It is situated today about 22 kilometres from the Gulf of Siam, covered by modern rice fields (Higham and Thosarat 1998). Excavations revealed occupation by coastal hunter-gatherers who had lived there, briefly, in about 2400 BC. They chose to live on what was then a low promontory overlooking a large marine embayment, sheltered from the open sea to which access was gained by means of an inlet about 5 km to the north. Several other similar sites were also found round this embayment. The hunter-gatherers collected cockle shells from the sandy beaches in their thousands, and these accumulated into thick middens. But examination of the midden contents also revealed how they had gone out into the open sea to fish for bull sharks and eagle rays, and hunted seals. No evidence was found for the consumption of rice, and there were no domestic animal bones. However, they made pottery vessels, and ground and polished their axes. One burial was found, an old woman, interred in a seated, crouched position under several pottery vessels. Clearly, these people inherited a long tradition of adaptation to a marine environment, and could stay in the same settlement for long enough to feel a need to fashion and fire pottery vessels, for if a group is regularly moving from place to place, a pottery vessel being fragile, has little value.

Figure 2.1 Map of the sites mentioned in the text. Nong Nor, 2. Khok Phanom Di, 3. Quynh Van, 4. Bau Tro, 5. Spirit Cave, 6. Khok Phanom Di, 7. Ban Non Wat, 8. Ban Chiang, 9. Ban Kao, 10. Khok Charoen, 11. Moh Khiew, 12. Man Bac, 13. An Son, 14. Non Pa Wai, 15. Non Nok Tha, 16. Ban Na Di, 17. Khao Sam Kaeo, 18. Ban Don Ta Phet, 19. Prohear, 20. Phum Snay, 21. Noen U-Loke, 22. Non Muang Kao, 23. Non Ban Jak, 24. Tha Kae, 25. Phu Noi, 26. Oc Eo, 27. Angkor Borei, 28. Nen Chua, 29. Go Thap, 30. Go Xoai, 31. Phum Phon, 32. Ishanapura, 33. Sdok Kak Thom, 34. Angkor, 35. Wat Phu, 36. Banteay Prei Nokor.

As the sea level retreated, so Nong Nor ceased to be attractive for those long accustomed to life on or near the shore. Four centuries later, in about 2000 BC, we can track down a second hunter-gatherer community just 14 km to the north, at a site called Khok Phanom Di (Higham and Thosarat 2004). This was altogether a different settlement to Nong Nor. Critically, it was located at the mouth of the estuary of the Bang Pakong River. A mangrove-fringed estuary is one of the richest habitats known, in terms of natural abundance of food and energy. This is firmly based on the fact that mangroves continuously shed their leaves, thus providing the basis for a food chain that begins with small marine organisms, and proceeds through their predators, to the small fish, crabs and shellfish, thence to larger fish and ultimately, to human communities. Moreover, estuaries seasonally attract large shoals of breeding fish while the rivers and open sea offer further opportunities for fishing and easy access to exchange routes. All these advantages encourage permanent settlement rather than the mobility so often associated with hunter-gatherer communities. There were doubtless disadvantages, not least the swarms of malarial mosquitoes which one associates with such habitats. However, deep in the lowest occupation layers at Khok Phanom Di, we can reconstruct many aspects of the life of a maritime hunter-gatherer society.

A direct link is found between the first people to occupy the site and those of Nong Nor, through their very similar styles of pottery vessels and bone fishhooks, awls and points. Both groups also fashioned highly polished stone adzes, made from stone that had to be imported. At Khok Phanom Di, caches of such adzes were found, together with the clay anvils and burnishing stones that were used first to form and then to polish their pottery vessels. The mound rapidly rose in height as shellfish were brought to the site, and then dumped into middens. Anadara granosa was the dominant species, a bivalve adapted to the sandy beaches that must have stretched out to sea at low tide. These middens also contain the remains of a variety of fish, and crabs. What we don’t find in the early levels, are any signs of domestic animals. There are no dog bones, nor any sign of pigs or cattle. Nor is there any evidence for the cultivation of rice, although some fragments of rice chaff were present as temper in exotic potsherds (Vincent 2004). There were also a few indications of rice in the occupation layers, but it is held unlikely that it was locally cultivated, since rice is not adapted to salty conditions.

Treatment of the dead is a key to unlock social aspects of an extinct society. The earliest occupants of Khok Phanom Di buried the dead in shallow graves, within their middens. A child was found interred in a foetal, crouched position, while two men and a woman were placed extended, on their backs with the head directed to the east, one accompanied by a handful of shell beads. Two of the adults and the child exhibited bone conditions that suggested that they suffered from a blood disorder that, while shielding the individual from malaria, caused anaemia. This genetic disorder may well reflect many generations of survival in a malarial environment (Tayles 1999).

If Khok Phanom Di had been abandoned after this initial occupation phase, it would have closely resembled what was found at Nong Nor. However, the favourable estuarine conditions enabled this society to continue living there for a further four centuries, and as the mound rapidly accumulated, so we can reconstruct its progression through time against a backdrop of changes in the physical and social environment. This sequence is divided into seven mortuary phases. The second of these reveals a marked change in the treatment of the dead. They were now interred in tight clusters, laid out on a chequer-board pattern, still with the head to the east. In some cases, mineralized wood under the skeleton suggested that they were placed on a bier, and to add to the increasingly complex rituals that attended funerals, bodies were sprinkled with red ochre and wrapped in a shroud of asbestos sheets. Mortuary offerings now included brilliantly polished and decorated pottery vessels. One man stood out for his lavish ornaments that included 39,000 shell beads. Cowrie shells were also found as mortuary offerings, as well as a rhinoceros tooth and bangles fashioned from fish vertebrae. The layout of the burial clusters was complemented by a thick shell midden that ran between them, and even turned at right angles, as if it had accumulated against a structure of some sort. This, combined with the presence of the holes that would once have held the upright posts of a building, strongly suggests that there had once been mortuary buildings to contain the dead.

The study of the bones themselves reveals a very high proportion of newly born infants. The adults, many of which continued to exhibit symptoms of anaemia, had well-developed bones with robust musculature, which Tayles (1999) has suggested might have been the result of such activities as paddling canoes, or kneading and converting clay into pottery vessels.

The third mortuary phase continued in the established tradition of interment in tight groups lying over the ancestors, associated with finely made pottery vessels and shell jewellery (Figure 2.2). Half of all graves also continued to contain newly born infants. However, during the course of this phase, there were also a series of important changes. The most significant of these comes from the study of isotopes ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series

- 1 The Debates

- 2 Southeast Asia in 2000 BC

- 3 Laying the Foundations

- 4 The Coming of the Age of Bronze

- 5 The Iron Age

- 6 The Transition into Early States

- Bibliography

- Index