![]()

CHAPTER 1

Criminal Justice and the Welfare of Children

Crime does not exist. Only acts exist, acts often given different meanings within various social frameworks.

Christie 2004: 3

All the societies we are dealing with here have come to use a criminal justice system, but not all of them use it for children and, when they do, they use it in very different ways. In this chapter we set out, briefly, the issues raised by employing a criminal justice system and show how they led, at the beginning of the twentieth century, to attempts to use other means or to alter the principles and practices of criminal justice when the offender is a child.

In all societies there are types of behaviour that incur disapproval, or anxiety, among certain groups, and societies devise ways of coping with this – religious mechanisms, local community actions, family norms. The focus of disapproval shifts, and the type of sanctions changes, but agreement and disagreement within and between groups in society over what is acceptable behaviour is always present. The same behaviour may be seen as ‘normal’ by some or at one point in time, ‘anti-social’ or ‘criminal’ at another. Alongside the state’s criminal justice system, Russian peasant communities operated their own systems of ‘summary justice’, with their conventions, rituals and punishments (sometimes fatal) meted out to those who offended norms of appropriate behaviour. School playgrounds everywhere usually have their own very clear rules on acceptable behaviour and procedures for meting out punishment to those who infringe them. In an environment, such as a prison, the prisoners’ community will establish their own rules and methods of enforcing them to ensure ‘order’ and justice (Олейник 2001). ‘Criminal’ means that society’s rulers have decided which acts are unacceptable, and have created procedures – a criminal justice system – for dealing with them.

All ruling authorities, whether self-appointed or elected, must show that they can exert authority – both to defend their right to make the rules and to defend the realm for which they claim responsibility. A centralized authority, striving to extend its reach over the territory as a whole, claims priority for its rules, and needs to be able to enforce them. Order is critical. Rulers may use physical means, including violence by the army or police, to put down disorder or riots. They may use the security services or enlist the support of church, educational establishments and employers to instil good behaviour. All ruling authorities are anxious to retain the right to use extra-judicial methods against their enemies (who may include their own citizens, as happened under Fascism and Stalinism), and we have seen the issue resurfacing with the use of detention and torture in ‘the war against terror’. Yet concurrently many favour transferring part of the task of maintaining order to a justice system, closely associated with, but separate from, the political rulers themselves.

‘Law’ as a mechanism enables the sovereign to divest itself of everyday involvement in the settlement of disputes, between citizens or groups, and between citizens and the state, yet to retain authority (Glenn 2000; Holmes 2003). And this means creating procedures and finding people to implement them. A criminal justice system, it seems, is an admirable mechanism for transferring the direct management of dangerous and unruly behaviour to an agency, whose decisions will reflect the values of its more privileged or powerful citizens, while the rulers retain responsibility to provide institutions for the enforcement of the decisions. At the same time, rulers recognize that for the criminal justice system to work effectively judges must be seen to apply the law impartially; rulers and their servants should obey the law too, and for infringements they too will be charged and tried by impartial judges.

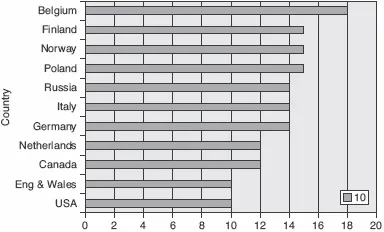

As we see, from Figure 4, almost all use a criminal justice system to deal with some of their children’s actions. But which actions? Decisions on this and on the role allotted to the criminal justice system, compared with that of the government or social organizations, the church or the family, vary enormously from one country to the next.

The question immediately arises: What is the thinking behind such different approaches to dealing with errant children? And this leads on to: What are the consequences (good and bad) for using a criminal justice system to deal with unacceptable behaviour by children?

What is a crime?

Young people in Russia (both school children and those on police record or in a colony) were asked what they thought a crime was.1 Some gave ‘correct’ answers:

breaking the law and the criminal code

illegal actions

Figure 4: Age of criminal responsibility, various countries

Notes: Poland: age 15 for serious crimes, 17 for more minor crimes; Russia: age 14 for serious crimes, 16 for more minor; USA: age varies by state.

and one (rightly) drew attention to the link between law and order:

Crime – it’s infringing order and law

The straightforward answer is: those actions that ‘the law’ identifies as ‘crimes’. The law changes, and ‘crimes’ appear or disappear. Exchanging currency and buying and selling foreign goods ceased to be crimes in Russia in the 1990s. Behaviour of young people that is found the world over – truancy, running away from home, loitering – falls into a category of ‘status crimes’ in the USA whereas in most European countries there is no such category. ‘Carrying a knife’ has become a new criminal offence in the UK. So ‘crime’ is determined by the law-makers but, in different societies, they approach their task differently. For the French there are contraventions, delit and crimes, which carry different kinds of sanctions, imposed by different agencies. If in Russia, to qualify as a crime an act must be considered to be socially dangerous, and all ‘crimes’ must be listed in the Criminal Code, in the UK ‘crimes’ are simply acts that a law classifies as such. Travelling without a ticket is a criminal offence in England, but only an administrative misdemeanour in Russia. Hence the same act will or will not be a crime in one country, depending upon the law and the age of criminal responsibility: cross the border from England into Scotland (although the traveller may not be aware of where the crossing is) and the rules change.

Law then creates ‘crime’. As Christie puts it, ‘Crime does not exist. Only acts exist, acts often given different meanings within various social frameworks’ (2004: 3). There are those who decide on the ‘law’ and there are procedures and institutions to ensure that the law is observed.

Property, violence and statistics

Many of the Russian children who were asked ‘what is a crime?’ thought in terms of concrete examples of bad behaviour:

murder, stealing, robbery

thieving

murder, stealing

murdering someone selling drugs, murder, stealing

it’s murder, robbing, it’s illegal activity

stealing cars, or from kiosks, or beating someone up

In their answers we see the two dominant ‘categories’ in criminal legislation in all our societies: acts against property and acts of violence but, even so, some kinds of property issues and types of violence have tended to occupy the law-makers.

Theft, burglary, and in some countries dealing in stolen property, dominate the code books and consequently the statistics. Such behaviour is age-related and income-related. These are young persons’ activities, and those of deprived young persons. Tax evasion, fiddling expense accounts, corporate theft – those adult white-collar practices – have not traditionally occupied such a dominant place in the code books, in the statistics, or in public discussion of ‘crime’. Recently, very recently, they have begun to attract more attention. But is there less of this behaviour than of theft by young people? Wilful damage to property, vandalism – is this as socially damaging or as dangerous as the dumping of toxic waste, developers breaking agreements on the preservation of green zones, or the export of arms to dictators?

At first sight crimes of violence against the person, as defined in law, seem to be more straightforward: murder, grievous bodily harm, assault. These are the recognized crimes of violence. But governments everywhere are anxious to keep violence committed by police, prison officers or the military out of the public gaze and, where possible, out of the ordinary justice system. Mugging is predominantly a young person’s pastime – mugging other young people – and they get caught. But what about those adult patterns of violent behaviour – domestic violence, for example, which only relatively recently, and not as yet in Russia, has entered the statute books as a crime? Child abuse? These violent acts remain much less prosecuted. Yet do we really think that less domestic violence occurs than mugging on the streets?

Our criminal justice systems have traditionally identified as ‘crimes’ activities or behaviour that will cause the ‘offenders’ to be drawn disproportionately from among the young male and more deprived sections of the population.

As the criminal law is in the main directed against forms of behaviour associated with the young, the working class, and the poor, we should not be surprised to find that, officially, it is these groups that are ‘found’ to be the most criminal. (Muncie 1999: 37–40, 118–24)

The most ‘criminal’ age-cohort, everywhere, is that of young men between the age of 18 and 30. They seem to be the group that rulers feel are most dangerous, most unruly. They dominate the statistics and the prison population. Women everywhere appear as a small minority. Their deviant behaviour has tended to be subject to other kinds of control, and seen as less dangerous.2 So the question arises: is ‘crime’ an appropriate descriptor of children’s behaviour?

Official crime rates, recorded by the police, are hard enough to interpret for one society; doubly difficult if we want to make comparisons between societies, whose legislation differs on the definition of criminal acts, whose procedures for recording crimes differ, where public attitudes towards the police vary markedly, and the police’s recording of incidents differs. The legislation changes and new ‘crimes’ appear. If the local population becomes less trusting of the police, they may report fewer crimes and the crime figures will show a decrease, although nothing has changed in the incidence of such activities. Social attitudes may change: when women feel they can and should report rape, the statistics suggest that rape has increased. Changes are introduced in the reward system for the police (bonuses are tied to solving cases) and (hardly surprisingly) the recorded figures of difficult-to-solve crimes will drop.3

The importance of police behaviour has led some to argue that ‘Official statistics reflect not patterns of offending but patterns of policing’ (Muncie 1999: 20). I would put it a little differently: crime rates represent the result of many different responses to rulings from above. This means that we need to approach them and any claims made on their behalf with a great deal of caution. There are many interested parties in such debates: politicians, police, all the agencies of the criminal justice system, and the public. But the role of the police is critical in determining the future fate of young people, and we shall return to this in later chapters.

Everywhere only a small percentage of ‘criminal acts’ gets reported to or recorded by the police. So maybe unrecorded crime looks different? In order to get a better sense of criminal behaviour, some countries, including the UK, have introduced both victim surveys (where a representative sample of the adult population is asked whether it has been a victim of crime during the past 12 months and, if so, of the type of crime) and self-reporting surveys (where young people are asked whether they have committed a crime, and if so, of what kind). No one suggests that any of these approaches allows a ‘true’ representation of criminal behaviour, but they can offer a better picture of long-term trends than can officially recorded crime data. Surprisingly, perhaps, given all the factors that can affect recorded crime data, data from such surveys tend to support the official trends.

The staying power of criminal justice systems

Both (civil) continental and common law are based on the following principles:

1. a) There exists a public (written and accessible) listing of those actions that are ‘crimes’, and ignorance of the law is no excuse;

b) the individual is responsible for his/her actions.

2. a) All are equal before the eyes of the court;

b) the accused must have the right of defence;

c) the judge is independent, and guided by the law, and only the law.and, further:

3. a) The court should determine whether the accused did commit the crime;

b) the judge should award a ‘proportionate’ sentence, i.e. proportionate to the offence;

c) the court decision is upheld by the government, which is responsible for seeing that there are agencies to ensure its implementation.

To understand this quite complicated set of principles, we need to remember that criminal justice, as a mechanism, evolved in societies where inequality in wealth and power prevailed, and that criminal justice systems are designed by the powerful, and powerful adult males at that.

Take the principle that the individual is responsible for his actions, and all are equal before the court. If a rich man steals a loaf of bread, and a poor man steals a loaf of bread, they are both equally culpable. It is the offence that matters. No privileges allowed here. Both have the same right of defence. Both should be sentenced to the same punishment, if found guilty. ‘Equal cases have to be treated equally and according to the rules. But of course cases are never equal, if everything is taken into consideration’ (Christie 2004: 76). There is no good reason for a rich man to steal a loaf of bread, and should he absentmindedly walk off with one, he can pay for a lawyer to explain the mistake, and the judge will recognize that he is not really a bread-stealer. . .and so on. It is then a system that advantages those who have already established a place for themselves in society. Is it then appropriate for children?

Had it not proved itself to be such a flexible and useful mechanism for deciding who is a danger to soci...