![]()

Part One

The Eighteenth-Century Background 1740–1804

![]()

1

Peoples, States and Societies

The purpose of this chapter is to describe eighteenth-century Eastern Europe in general terms at the outset of our period. This involves, first of all, the human geography of the region, the peoples inhabiting it. Second is a summary of the political geography: the states of Eastern Europe, including their historical evolution and the changing nature of their relationships with each other in this period. Third is a survey of economic and social conditions, and the way in which these determined political systems within individual states.

PEOPLES AND LANGUAGES

The sheer multiplicity of peoples in Eastern Europe is at first sight bewildering. Altogether there were eight major ethnic groups settled by the eighteenth century, speaking some two dozen languages and practising half a dozen religions. (See Map 1.)

One of the most important points to make about the ethnography of Eastern Europe (as of Western Europe) is that the region was settled for the most part by successive waves of peoples arriving from outside. For centuries Eastern Europe was used as a sort of doormat by Germanic, Slavic, Turkic and other peoples, all seeking entry to the region, fighting, conquering or expelling each other. Indigenous peoples, like the Greeks and Albanians, were either conquered or pressed to the mountainous margins of the region; sometimes territory could be reclaimed, sometimes the newcomers were assimilated by the conquered population, as happened with the Turkic Bulgars and their Slav subjects. The last major influx of people was the invasion of the Magyars in the ninth century, but recurrent wars and conquests ensured that the ethnographic balance was constantly being altered.

The results of this process were twofold. First, the peoples of the region were, by the eighteenth century, highly intermixed, in the sense that many areas contained numerous ethnic groups. Second, the centuries-long process of settlement and resettlement meant that very few peoples, let alone individuals, could claim any sort of direct, unbroken lineal descent from their ancient ancestors. The very languages that the inhabitants of the region spoke betrayed a complex, multi-ethnic inheritance. In Eastern Europe, as elsewhere, everyone was a mongrel.

Map 1 Languages of Eastern Europe

Source: ‘Languages of Europe’. Palmer, R.R. and Colton, J., 1965, A History of the Modern World, 3rd edn, New York, 437.

Apart from Celtic and other early inhabitants of whom only archaeological traces remain, the Greeks were among the longest established peoples. The degree to which eighteenth-century Greeks, and the language they spoke, were descended from the ancient Greeks has been contested; what cannot be denied is that a belief in this link with the Hellenic past was to prove a powerful element in modern Greek nationalism. More important in the context of the eighteenth century was the fact that the Greek world was a far-flung one: Greek settlements were to be found across the region and the largest of these were in Constantinople and Smyrna, not in the Greek Peninsula.

Equally long established were the Albanians, an indigenous people originally inhabiting the Roman province of Illyria but gradually crowded into the mountains of the western Balkans by the arrival of new peoples. Converted in large numbers to Islam following the Ottoman conquest, Albanians became a favoured people in the Ottoman Balkans, and the area of Albanian settlement slowly spread into areas bordering on present-day Albania.

On the south-eastern shores of the Baltic, the peoples collectively known as Balts were one of the first groups of Indo-European language speakers to arrive in Europe, around 2000 BC. Two of these peoples, the Prussians and the Curonians, had been assimilated following the conquest of the Baltic shore by the Teutonic Knights in the Middle Ages; they left behind their names in the shape of the (German) Duchy of Prussia and the coastal area known as Courland. The other two peoples, Letts or Latvians and Lithuanians, survived, the Letts as a subject people of the Teutonic Knights and then Russia, the Lithuanians by uniting with Poland in the fourteenth century.

Two peoples, widely separated, represented the Romance, or Latin-based, group of languages. In the Istrian Peninsula and along the Adriatic coast lived substantial numbers of Italians, most of them still subjects of the Venetian Republic. On the other side of the Balkan Peninsula, the inhabitants of what was to become today’s Romania claimed descent from the ancient Roman colonists of Dacia. Romanian is undoubtedly a Latinate language, though one showing heavy traces of Slavic, Turkic and other tongues.

The most numerous language group in Eastern Europe is that of the Slavonic-speaking peoples. Originating in the area between the Dniester and Vistula rivers, the Slavs were to begin with an undifferentiated mass of tribes, all of whom spoke essentially the same language. From the first to the sixth century onwards, however, the Slavs began to fan out in different directions, settling in what is now Russia proper, in the lands further to the west, and in the Balkans. The longer they remained settled in their respective new homelands, the further apart grew their languages, to the point where philologists nowadays distinguish between three main subgroups. The East Slavs speak Russian, Ukrainian and Byelorussian or White Russian. The West Slavs are the Czechs, Slovaks and Poles. The South Slavs include Slovenes, Croats, Serbs and Bulgarians. Croats, Serbs and Bulgarians all take their names from Iranian or Turkic peoples who imposed themselves on the Slavs already settled in the Balkans and were then assimilated by them.

One group of peoples who have nothing in common, linguistically, with their Indo-European neighbours are the Finno-Ugrians. This includes the Estonians, who had arrived on the north-east coast of the Baltic with their close relatives, the Finns, by Roman times; another related people, the Livs, left their name to the coastal area of Livonia after conquest by the Teutonic Knights. Much later, in the ninth century, the Magyars, or ethnic Hungarians, burst upon the European world from the east. They rampaged as far afield as Burgundy and northern Italy before settling down in the Pannonian Plain, which forms today’s Hungary. In doing so, the Magyars drove a permanent wedge between the West and South Slavs, over several of whom they gradually established a dominion in the early Middle Ages.

A special role had been played in Eastern Europe, for centuries, by the Germans. The various Germanic peoples had been knocking at the doors of the Roman Empire long before the Slavs, and by the end of the first millennium Germanic kingdoms, including the vast domain founded by Charles the Great (Charlemagne) in AD 800, which came to be known as the Holy Roman Empire, were part of the state structure of medieval Europe. The first German outpost in Eastern Europe was the Duchy of Austria, the ‘eastern realm’ (Österreich), created in the ninth century by Charlemagne as a buffer zone against barbarians from the east. Then, in the early Middle Ages, German influence was extended along the Baltic littoral when the Teutonic Knights undertook the ‘northern crusades’ against the pagan peoples of the region, exterminating some like the Prussians, subjugating and Christianising others. The final extension of German influence in Eastern Europe was more peaceful: throughout the late Middle Ages, there was a steady influx of German artisans and tradesmen, clerics and artists, many invited into kingdoms whose rulers were acutely conscious that their realms lacked such specialists. As a result German settlements could be found the length and breadth of Eastern Europe, from the Baltic ports to Transylvania, from western Bohemia to St Petersburg. Ethnic Germans were above all an urban class, although the oldest communities, such as the Saxons of Transylvania, were also agriculturists.

Among the latest entrants into the Balkans were the Ottoman Turks. This was a consequence of the conquest, by the late sixteenth century, of south-eastern Europe as far north as central Hungary by the Ottoman sultans, even though Hungary at least had been reclaimed for Christendom by 1699. Apart from the religious divide created by this subjection of the Balkans to an Islamic power, the dominance of the Ottomans for so long meant that by the start of our period a sizeable proportion of the population was ethnically different as well. The term ‘Ottoman’ denotes the Muslim ruling class rather than a single ethnic group; however, in so far as the Ottoman conquest brought in its wake large numbers of ethnic Turks in the form of administrators, soldiers and their hangers-on, it altered the demographic balance of the Balkans substantially.

As a result of their dispersion across the Mediterranean and European world since Roman times, Jews by the eighteenth century were to be found in many parts of Eastern Europe, and in several cases had been there for centuries. In most of the region Ashkenazis predominated, while in the Ottoman Empire there had been an influx of Sephardis from Western Europe in the sixteenth century. Virtually everywhere, with the partial exception of the Ottoman Empire, which tolerated monotheistic religions, Jewish communities were at best a tolerated minority within their ‘host’ society, at worst subject to appalling and repeated indignities and persecution. Jews’ retention of a distinctive religious rite and customs meant that they remained a class apart, repeatedly subjected to restrictions on their faith, where they lived, what occupations they could pursue. These very restrictions ensured that Jews, wherever they settled in Eastern Europe, tended to establish themselves as a commercial class. They made their often highly precarious livings as merchants, as craftsmen, as bailiffs for the landowner class and, above all, as moneylenders to rich and poor alike, and in the case of a select few lending millions to European princes.

Suffering an even worse plight than the Jews were Eastern Europe’s Gypsies or Roma, an Indo-European people from India who had arrived in the Balkans via the Byzantine Empire by the eleventh century or even earlier. Gypsy communities spread across Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, working as metal craftsmen, musicians, even soldiers, but everywhere they were treated as aliens, the lowest of the low, and persecution forced on them a wandering, unsettled way of life. This in turn confirmed the Gypsies’ image as rootless, and they remained trapped between the popular prejudice which excluded them and the inveterate desire of local rulers to regulate them and, by forcing them to settle, to make them taxable. In the Romanian principalities of the Ottoman Empire, Gypsies had for a long time been treated virtually as slaves, and although this was exceptional, the position of Gypsies elsewhere was generally invidious.

STATES

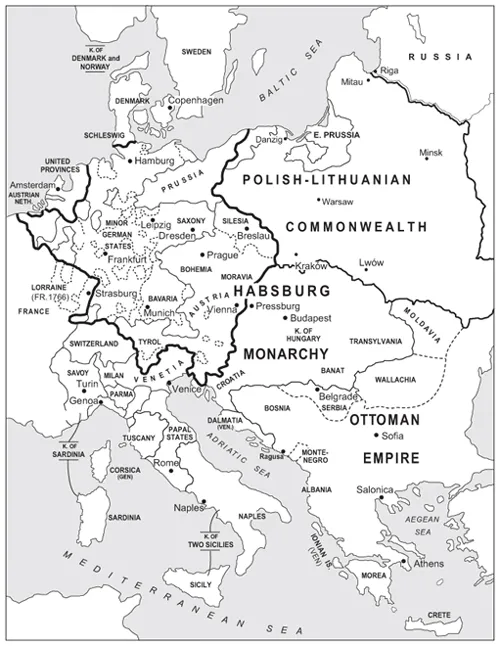

The political geography of Eastern Europe in 1740 did not reflect the ethnic diversity outlined above. Instead, the region was divided between seven sovereign states, all multinational, all the product of complex historical developments. (See Map 2.)

Least significant was the city state of Ragusa (today’s Dubrovnik). Though overshadowed throughout its long history by more powerful neighbours, Ragusa had profited from its strategic position at the southern end of the Adriatic and as the western end of major trade routes across the Balkans. The Ottoman conquest of the peninsula, while it spelt economic decline for the Venetian Republic and for much of the eastern Mediterranean, was by contrast an opportunity for Ragusa, which benefited from the fact that it posed no threat to Ottoman power and was at the same time a valuable conduit for trade and diplomacy. Largely populated by Slavs, in cultural character Ragusa had more in common with its fellow city states in Italy. Politically it was a republic, dominated in the eighteenth century by an oligarchy of leading merchant families.

The Republic of Venice, which still ruled over most of the Dalmatian coast to the north of Ragusa, was also a city state in decline, though more sizeable and a former regional great power. Much of its energies had been devoted to combating Ottoman encroachments on its very doorstep. Venice retained its grip on the Istrian Peninsula and the Dalmatian coast until the Ottoman threat was past, but by the eighteenth century it too was decrepit, its commerce evaporated and its foothold on the eastern Adriatic dependent on the goodwill of the much more powerful Habsburg Monarchy.