![]()

1

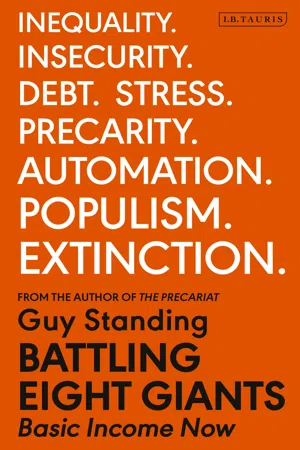

Slaying giants with basic income

What is basic income? At its core, it would be a modest regular payment to each individual to help them feel more secure and able to purchase necessities for living.

There is nothing in the concept itself to say how much it should be and nothing to say it should be paid instead of any other policy or that it should be financed by a steep rise in income tax, although obviously the funds would have to come from somewhere. Of course, at some stage one has to say how much should be paid, why it is desirable and even necessary, what are the answers to commonly stated objections and how it could be afforded. Answering these points is the main purpose of this book.

There are many reasons for wanting a basic income system, some uniquely modern, some that stem from way back in our history, first enunciated in The Charter of the Forest of 1217. One of the two foundational documents of the British Constitution, the other being the Magna Carta sealed on the same day, the charter asserted that everybody had a right of subsistence from ‘the commons’. This is a human or citizenship right, not something dependent on specific behaviour or some indicator of worthiness, or merit.

This book argues that the primary reasons for a basic income are ethical and moral. Although basic income would be a more effective means of reducing poverty and inequality than the current system, introducing basic income is first and foremost a matter of social justice. The wealth and income of all of us are due far more to the efforts and achievements of the many generations who came before us, than they are to what we do ourselves. If we accept the practice of private inheritance, as all governments have done, which in its simplest terms gives a lot of ‘something for nothing’ to a minority, then we should also honour the principle of social inheritance.

If we accept the existence of ‘the commons’, which I would define as the common resources and amenities, natural or social in origin, bequeathed to us as a society, then we should accept that over the centuries – and egregiously during the austerity era – there has been organized plunder of the commons by privileged private interests at the cost of all of us as commoners.1 Seen in this way, those who have gained from this plunder should compensate commoners in general for the loss.

As we are all commoners, the compensation should be paid to all, equally and without behavioural conditions. Thomas Paine, writing in the late eighteenth century, best captured this principle – that we all own the wealth of the land, the ultimate commons. So, we might call this the Painian Principle.

A second ethical justification is that, however modest the amount, a basic income would enhance personal and community freedom. It would strengthen the ability of people to say ‘no’ to exploitative or oppressive employers and to continuation of abusive personal relationships. And it would strengthen what is often called ‘republican freedom’, the ability to make decisions without having to ask permission from persons in positions of power. It would not do this wholly but would be a move in that direction. One way of putting it is that the emancipatory value of a basic income, by expanding freedom, would be greater than its money value – the opposite of most social policies, which reduce freedom.2

The third ethical justification is that it would provide every recipient, and their families and communities, with basic security. Security is a natural public good – you having it does not deprive me of it, and we all gain if others have it too. Whereas too much security can induce ‘carelessness’ and indolence, lack of basic security reduces the ability to make rational decisions and threatens health and well-being.

A basic income would also strengthen social solidarity, including human relations: it would be an expression that we are all part of a national community, sharing the benefits of the national public wealth created over our collective history. It is essential to revive the ethos of social solidarity that has been eroded in recent decades by excessive individualism and competition.

Although a basic income would be paid individually, it is not individualistic. Being quasi-universal and equal, unlike means-tested social assistance or tax credits, basic income would discourage ‘us and them’ divisions and confirm that all of us are of equal worth. Though paid to all individuals as equals, its benefits would also be social, offering to improve intra-family relationships, community cohesion and national solidarity.

This book emanated from a report requested as a contribution to policy development by the Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer. It begins by defining a basic income, then considers the unique combination of pressures that make it almost imperative for any progressive or ecologically principled government to wish to implement it. The book recognizes that a system with a basic income at its base would represent a principled reversal of the trend towards means-testing, behaviour-testing and sanctions that has evolved into Universal Credit (UC). Accordingly, it includes a critique of that trend, along with a critique of similar policy directions regarding disability benefits. Those who are critical of basic income should tell us what alternative they would propose or say they accept UC for what it is.

To be clear from the outset, this book advocates a strategy with the following features:

(1) It would reduce poverty and inequality substantially and sustainably.

(2) It would make nobody in the bottom half of the income distribution system worse off.

(3) It would enhance economic security across the country.

(4) It would not involve any dramatic increase in income taxation.

(5) It would not involve any dismantling of public social services and would be compatible with a strategy to achieve desperately needed public service regeneration after the savage depredations of austerity.

(6) It would reduce the number of people dependent on, and subject to, means-testing and behaviour-testing.

(7) It would contribute positively to the urgent fight against ecological decay.

Defining basic income

Let us start by defining a basic income, bearing in mind that the primary objective is to improve lives while helping to build a twenty-first-century income distribution system that would leave nobody who is currently economically insecure worse off. The defining aspects of a basic income are as follows:

Basic. It would be an amount that would make a significant difference to the income of those currently earning or receiving low incomes. It would provide some basic security, but by no means total security. The amount could start at a low level and rise as resources are mobilized and as experience with the impact grows.

Cash. It would be delivered in money form or in some acceptable substitute, provided people are free to spend the income as they wish. So, it would not be paternalistic, dictating choice, as vouchers or food stamps do, for example.

Regular and predictable. The money would be paid at regular intervals, probably monthly, automatically as a right. This contrasts with uncertain means-tested and behaviour-tested benefits that must be applied for, can vary in value month to month and may be reduced or withdrawn altogether. The perceived value to the recipient would thus be greater than the same amount if paid via means-tests and behaviour-tests.

Individual. It would be paid to every individual regardless of gender, race, marital or household status, income or wealth, employment status or disability. It would be paid equally to men and women, with – in principle – a lower amount for each child under the age of 16 that would go to the mother or primary carer. It is important that it would not be paid according to household or family status, since that is a behavioural matter.

Nothing in the concept of basic income precludes additional supplements to cover special needs. The intention is to provide everybody with equal basic security. So, anybody with a medically accepted disability involving extra costs of living and/or a lower probability of being able to earn income should receive a ‘disability benefit’ on top of the basic income. However, unlike current policies, the entitlement should be based solely on medical criteria and likely costs, and not on means-tests and arbitrary capacity-to-work tests.

Unconditional. The basic income would be paid without the imposition of behavioural conditions such as job-seeking. Research shows that making benefits conditional on certain behaviours is counterproductive and results in the penalization and punishment of vulnerable people and minorities. The basic income would be unconditional in terms of past activity, present activity and future use of the money.

Quasi-universal. The basic income would be payable to every legal resident, though with a delay in entitlement for legal migrants. To avoid potential confusion and misrepresentation, this book will not employ the widely used terms ‘universal’ and ‘citizens’ basic income’: the basic income would not be paid to everybody coming to Britain nor to every UK citizen, since the several million living and working abroad would be excluded. Citizens’ entitlement should be restricted to those who are usually resident in the country.

The term ‘citizens’ basic income’ implies that non-citizens living and working in Britain would be excluded, which would be unfair. A simple pragmatic rule could be entitlement after legal residence for at least two years. Beyond that, if the UK remained in the European Union, entitlement would have to accord with EU law.

Claims that a basic income would induce ‘welfare tourism’ by migrants are unfounded. A means-tested system, like the one operated in Britain in recent years, does worse in this respect, since it effectively puts those most in ‘need’ at the front of the queue. As recent migrants are among the most needy, a perception is easily (albeit falsely) conveyed that they are gaining at locals’ cost. This does not mean that other migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers should be ignored altogether; their needs should be covered by other schemes.

Non-withdrawable. The basic income would be payable to all those entitled and would not be withdrawn as income or personal circumstance changed, as is the case with means-tested benefits.3 Subject only to change by parliamentary legislation, it would be a permanent right.

Although there is no need for the basic income to replace any existing benefit, its introduction would automatically result in a reduction in public spending, since some recipients of means-tested benefits would be lifted above the threshold of entitlement. Even they would gain because, as noted earlier, a certain benefit is worth more than an uncertain one of the same amount.

There are two forms of basic income considered in this book. One refers to a regular cash payment that substitutes for some other state benefits and subsidies. This is the form commonly considered in analytical and empirical work in Britain, notably by the Citizen’s Basic Income Trust. Usually a ‘revenue neutral’ constraint is imposed, meaning that the basic income is paid for by rolling back some means-tested benefits and subsidies and by raising income tax rates.

The second form is more radical and involves paying an additional benefit, which may be called a common dividend. This rests on the premise that every usually resident citizen and legally accepted migrant is entitled to a share of the collective accumulated wealth of the country and to compensation for loss of the commons – common resources beginning with the land, water and air, extending to our inherited social amenities and bodies of ideas – that should belong to all of us equally. The dividend could be paid from a Commons Fund, built up from levies on commercial exploitation of the commons, which would head off criticism that people with jobs would be taxed more to pay benefits for ‘non-workers’. Basic income could even be depicted as integral to a system of ‘dividend capitalism’, or as ‘eco-socialism’, depending on one’s political preference.

Why is basic income needed?

The ethical justifications given at the outset – social justice, security, freedom and solidarity – are powerful reasons for wanting a basic income system. But the urgency of needing it now reflects a perfect storm of factors that have created the basis for a remarkable coalition of supporters.

Most debate in Britain on social policy refers back to William Beveridge’s epoch-defining report in 1942, which established the principles that would bring us the National Health Service (NHS) and the post-war system of social security that is now in tatters. But the type of economy and labour market of Beveridge’s time differed sharply from current realities. We are living in...