![]()

‘Mother India’

The story of a film that receives great or even above-average success is the sum total of facts and figures, apocryphal and anecdotal stories, myths and legends. If the film was made some time ago, it is about memory – personal and collective. At times, it is necessary to be cautious. There is the claim, for instance, that ever since its first screening Mother India has been in uninterrupted distribution, always on the programme at some theatre somewhere in India. Thinking this to be an exaggeration based on the immense popularity of the film, I looked through correspondence between film distributors, theatre owners and the production company, along with bill-book counterfoils, theatre-hall reports and advertisements in daily papers – all preserved in the official files of Mehboob Productions in Bombay.1 They confirm that ever since its first release in Bombay and Calcutta on 25 October 1957, the film indeed was in continuous circulation for over three decades – not only in India but all across the globe. However, this amazing history of film viewing and distribution did come to an end in the mid-1990s because of the boom in cable television and changing film-viewing tastes and habits.

Mother India, directed and produced by Mehboob Khan, was released in the Liberty theatre and four other theatres in Bombay. In Calcutta, it was released in the theatre chains Radha, Purna, Prachi and other suburban halls. Simultaneous release was considered for the Delhi circuit, but the première in Regal, Westend and Moti could only be arranged for 1 November 1957. By the end of November the film had penetrated every distribution zone in India.

The story actually begins some five years earlier. Mehboob’s first colour film Aan (1952), a stupendous success in the domestic market, had also inaugurated international distribution on a scale unprecedented for an Indian film. Flushed with success, Mehboob launched immediate plans to make another film, to be in colour and titled Mother India. In October 1952, Mehboob’s production company approached the Joint Chief Controller of Imports, for an import permit and sanction for raw stock sufficient for 180 prints. The maximum number of prints made for a film in those days was usually well below half that figure (usually around 60), and the JCC was not going to depart so sharply from the usual practice of releasing a limited amount of raw stock; and so protracted negotiations between the government and the production company began. The buying and selling of distribution rights, however, took off as soon as the project was announced in trade and film journals. Distributors already in business with Mehboob Productions and some new ones clamoured for the rights to Mehboob’s new venture. The foreign distribution rights were sold from 1954 on. Cancellations and renewals of contracts mark the beginning of a film that was famous, even though merely at a stage of planning, governmental sanction yet to come – even before any clear decision had been taken regarding the story and cast. Apparently the process of mythologising had started at the conception of this film. Ivan Lassgallner, a distributor in London, had done business with Mehboob in 1952–4; he wrote on 8 July 1957, ‘I hear you have completed your greatest film yet, Mother Of India’ (he would later distribute Mother India in the European market). ‘We will be privileged if we can distribute such a film as Mother India’, an Indian distributor wrote in 1956.

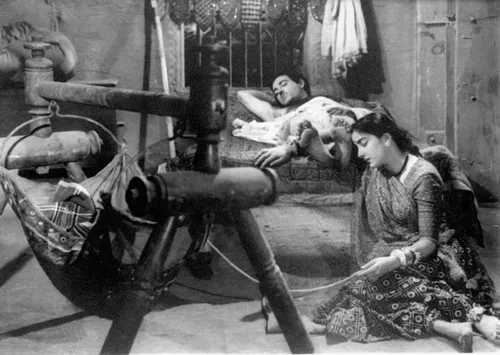

Radha sleeps at Shyamu’s feet (they are a repeated motif in Mother India): from a deleted scene

Mythology is, indeed, one of the wellsprings of the film, as a look at the nomenclature in the film alone would confirm. References to gods and goddesses, representation of rituals and celebrations, songs and dances form the bulk of the two hours and forty minutes running time. Pre-existing motifs (tales, proverbs, aphorisms), familiar designs and iconography are worked into its narrative and visuals. As the saga of a peasant family, the eventful story encompasses a long time frame. In addition, the title Mother India is connected with various nationalist discourses and the history of India’s struggle for freedom. The actors lend further lustre to the film’s aura; some became stars and legends in their times, some went on to become prominent political figures. And yet the myths – those within the film and those surrounding it – cannot fully explain its phenomenal success. Films with mythological topics and overtones do not always enjoy critical and box-office popularity. Foreign audiences would not have understood all the specific references to Indian myths and traditional motifs, but nonetheless Mother India was successful internationally.

But to know the film well, it is necessary to uncover facts and histories: aspects of conception and production over a period of five years. The grand project, naturally, involved many people; most of the technicians and studio hands, scriptwriters and musicians worked full time in the studio and drew a salary. The actors – the stars and newcomers, those playing secondary roles and the extras – were contracted for a period of ten months, to be present fifteen days a month. They were, as some recall, members of a family, spending long hours and eating together – staying together while on location.2

Mehboob and wife, Sardar Akhtar with UK distributor Ivan Lassgallner (seated)

Few people who had been associated with or witness to the film’s production are around. But incoming and outgoing letters, notes and memos, bills, receipts and accounts are preserved (some are missing) within the covers of over a hundred files. Not everything in them is connected strictly with the film: there are records of community dinners on Fridays, banquets for dignitaries (often on the lawn, with liveried waiters), donations made to various organisations, film projects planned but abandoned, the director’s attempts to improve film-making conditions in India. Together, they tell amazing stories, provide valuable information and help in the reconstruction of the film’s history.

* * *

Another starting-point in the story of Mother India is 1938, when Mehboob saw the Hollywood film The Good Earth (Sidney A. Franklin, 1937), based on a novel of the same title written by the American Nobel Prize-winner Pearl S. Buck. Mehboob planned to make a film on similar lines. But Bābubhāi Mehtā, a highly literate friend and source of story ideas, suggested another of Buck’s novels, The Mother (1934), which chronicles the life of a Chinese woman – her life with her husband and her lone struggle when he abandons her. She surrenders briefly to the seductions of an official moneylender; scarred but eventually stronger she devotes her life to her land and sons. At the end, the mother is a mere spectator of changing times – seeing her youngest son get arrested for being involved in the communist movement. Fond of portraying strong women protagonists, Mehboob preferred this alternative and Mehta wrote a story that gave rise to Aurat (The Woman, 1940).

The heroine of Buck’s novel is nameless, referred to only as ‘the mother’. The heroine of Aurat is called ‘Rādhā’. She is morally superior to the moneylender – indeed to everybody else. One of Radha’s sons turns to a life of crime; unable to reform him, and for the good of her community, Radha shoots and kills her son. Indian audiences embraced this portrayal of extraordinary moral and emotional strength and advertisements and reviews hailed the portrayal of this ‘quintessential Indian woman’. In 1952, Mehboob decided to base his new film on that earlier one, drawing upon that previous success. Aurat was being distributed internationally, as a result of the success of Aan, and the production company could be confident of foreign audiences too for the new film, the director’s most ambitious project to date.

1938 was also the year when a Bombay film title, Mother India (India Cine Pictures), caught Mehboob’s attention. Admittedly, Mehboob was jealous of its director Baba Gunjal and wanted to make his own Mother India. Normally film-makers tend not to repeat the title of a successful film but Gunjal’s film had not been a great success. Besides, it was more than a decade since its release and no copyright protected the title now. The phrase ‘Mother India’ was filled with resonance, connected as it was with the national history of independence. India as a new nation-state was barely five years old at the time Mehboob’s project was launched. So Mehboob was turning to or revisiting the past and was doing so in more ways than one. He planned to shoot extensively in and around the villages in which he and his parents were born and raised.

* * *

Mehboob Ramzān Khān was born in the first decade of the twentieth century to a Muslim family from the region of Billimoria (formerly belonging to the princely State of Baroda) in Gujarat. His first years are not documented well, but there are several accounts by writers who knew Mehboob. His father Ramzan, the village blacksmith, was affectionately called ghodé-nāl-Khan, for his ability to fix horseshoes. Barely literate, but with some ability to read his mother tongue, Gujarati, Mehboob dreamt of other things for himself; he frequently visited the city of Bombay with a desire to be in films. A respected man of the village, Ismail-guard (a railway guard working between Baroda and Bombay) helped the boy in these escapades; but those first attempts bore no fruit. He was married to Fatimā (from a very poor family) and a son Āyub was born.

A family friend Parāgjī Desai later helped Mehboob to get work at the Imperial Film Company, owned by the legendary Ardeshir Irani, remembered today for Ālam Ārā (1931), India’s first sound film.3 Several versions of the story concur to suggest that Irani was impressed with the boy’s strict adherence to religious duties (reciting the namāz at prescribed times of the day) and his horse-riding capabilities (Ramzan had been a cavalier in the Baroda State army). Irani gave Mehboob bit roles to play in his silent films, the first being one based on the Arabian Nights story, Alibaba and The Forty Thieves (1927). Mehboob must have been in his early twenties then. It is tempting to use a literary trope and say, it was as if someone had opened the door to his destiny, calling out ‘Open Sesame’. But the fact is that the role was of no consequence; the camera barely captured him. Years later, Mehboob would return as a director to this same studio spot and shoot the first scene of his film Alibaba (1940). The desire to return to the past runs through Mehboob’s life and films. During the initial days of struggle, Ismail-guard saw to it that Mehboob slept undisturbed on the benches of the Grant Road railway station in Bombay.4 However, Mehboob soon made his mark as an actor. This part of Mehboob Khan’s life history is a ‘rags to riches’ story, a ‘poor boy makes it big in the city’ story.

Mehboob’s first wife Fatima Khan with their first born Ayub Khan

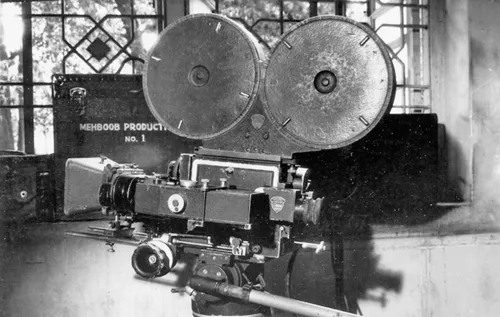

A Mitchell camera in the Mehboob Studios

Talkies came to India in 1931. Mehboob was transferred to Sāgar Movietone, another production house started by Ardeshir Irani. Beginning with the lead in The Romantic Hero (1931), Mehboob made a successful transition from silent films to talkies. However, he was disappointed not to get the lead in Ālam Ārā. Similar professional disappointments and his father’s death (he was now the sole provider for his wife and children) made him turn to direction. He joined up with assistant cameraman Faredoon Irani and laboratory assistant Gangādhar Narwekar. A Muslim, a Parsi and a Hindu were teaming up to do things together – films were being made in those days about this kind of cooperation. The studio heads decided to try him out and Mehboob directed his first film, a historical drama, Al Hilāl (The Judgment of Allah, 1935) – with the Katthak dancer Sitārā Dévī in th...