- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Historical Research Using British Newspapers

About this book

Thanks to digitisation, newspapers from the seventeenth to the twenty-first century have become an indispensable and accessible source for researchers. Through their pages, historians with a passion for a person or a place or a time or a topic can rediscover forgotten details and gain new insights into the society and values of bygone ages.Historical Research Using British Newspapers provides plenty of practical advice for anyone intending to use old newspapers by: * outlining the strengths of newspapers as source material * revealing the drawbacks of newspapers as sources and giving ways to guard against them * tracing the development of the British newspaper industry * showing the type of information that can be found in newspapers and how it can be used * identifying the best newspapers to start with when researching a particular topic * suggesting methods to locate the most relevant articles available * demonstrating techniques for collating, analysing and interpreting information * showing how to place newspaper reports in their wider contextIn addition nine case studies are included, showing how researchers have already made productive use of newspapers to gain insights that were not available from elsewhere.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

Pen & Sword HistoryYear

2016eBook ISBN

9781473859029Subtopic

British HistoryChapter 1

A Brief History of Newspapers in Britain

How the newspaper industry developed

Almost as soon as Johannes Gutenberg developed his revolutionary mechanical printing equipment in the mid-fifteenth century, news sheets, pamphlets and posters flew off the new-style presses. Up-to-date commercial information had a ready audience amongst a growing entrepreneurial class of traders, merchants and brokers and the London Gazette – founded in 1665 as the Oxford Gazette – is usually regarded as Britain’s first newspaper.

Commercial news and studies of weighty subjects were the respectable element of this early publishing industry and gradually evolved into reputable newspapers and periodicals. Other printed matter was more brash and brazen. Openly poking fun, challenging authority and disseminating scandal, it appealed to the baser instincts of human nature.

By the early decades of the eighteenth century, more than a dozen publications were in existence covering many types of news but their development was rued by the ruling classes and successive governments tried to suppress the flow of knowledge to the wider populace. One tactic was to restrict what could be circulated in print. Reporting anything about the business or apparatus of government, even if the story was truthful, or advocating change against the wishes of the ruling elite, was to court trouble. Harsh measures were taken against subversives who published unwelcome details and editors and writers could easily find themselves in court charged with seditious libel. This was a very serious crime which involved bringing into disrepute the public institutions of the country, such as Parliament, the monarchy and the legal system and those involved in running them. A guilty verdict usually meant punitive fines or jail, which effectively meant the end for the newspaper as it had been deprived of its money or its editor, or both.

A less draconian tactic was to tax every copy of a newspaper that was sold. This artificially raised its price, keeping those on small incomes out of the market but enabling the thriving commercial class to obtain information that was relevant for their business. This tax, known as Stamp Duty, was first imposed in 1712 but the low rate of a halfpenny (½d) per copy was not excessive. In 1797, as Britain’s ruling class shuddered at the thought of the French Revolution triggering a similar uprising by the British poor, Stamp Duty was increased to 3½d to try to suppress news about events across the Channel. The defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1815 failed to diminish upper class anxiety about a revolt amongst British workers and, in response to industrial unrest, Stamp Duty was raised to 4d, perhaps more than half the cost of the paper. By 1819, workers’ unrest had intensified and further measures were brought in to try to stifle dissent. More publications were brought within the scope of Stamp Duty and publishers had to enter into bonds and lodge money with the authorities to guarantee that they would only print what was lawful.

In the 1830s the official mood was more benign. The spectre of imminent revolution by the poor had ceased to haunt the ruling classes and some recognised that good newspaper editors were working to high professional standards. By 1836, Stamp Duty had been reduced to 1d as those who exercised political power began to realise how well their own interests might be served by informed public opinion. In 1843, Lord Campbell steered a Libel Act through Parliament. This made it easier for newspapers to report what was happening as editors could now defend themselves in criminal proceedings by demonstrating that the statement complained of was true and that printing it was for the public benefit. In 1855, during a period of relative social calm and economic prosperity, but also a time of war in the Crimean Peninsula, Stamp Duty on newspapers was abolished completely in Britain. After more than 150 years of official repression and obstruction, newspapers and their editors were at liberty to publish the truth, to highlight unfairness and to campaign for reform as they chose.

Key National Developments

Despite the background of suppression, the growing middle-class maintained a lively interest in keeping abreast of what was new and from the mid-eighteenth century onwards, a variety of national, provincial and local papers began to find readers who were keen to know what was being discussed in Parliament. The first national newspapers to develop into regular publications were established around 1770, the time when political parties with distinctive views were beginning to form. Although the ruling elite normally regard the general dissemination of news as undesirable, a contradictory factor was now at work: the need to keep people of the same political opinions up-to-date. Influencers were aware that news sheets could play an important role in this and, on occasions, formed links with a sympathetic editor to get their messages out to the literate public. This probably explains why, in a repressive climate, some newspapers managed to establish themselves and become regarded as respectable.

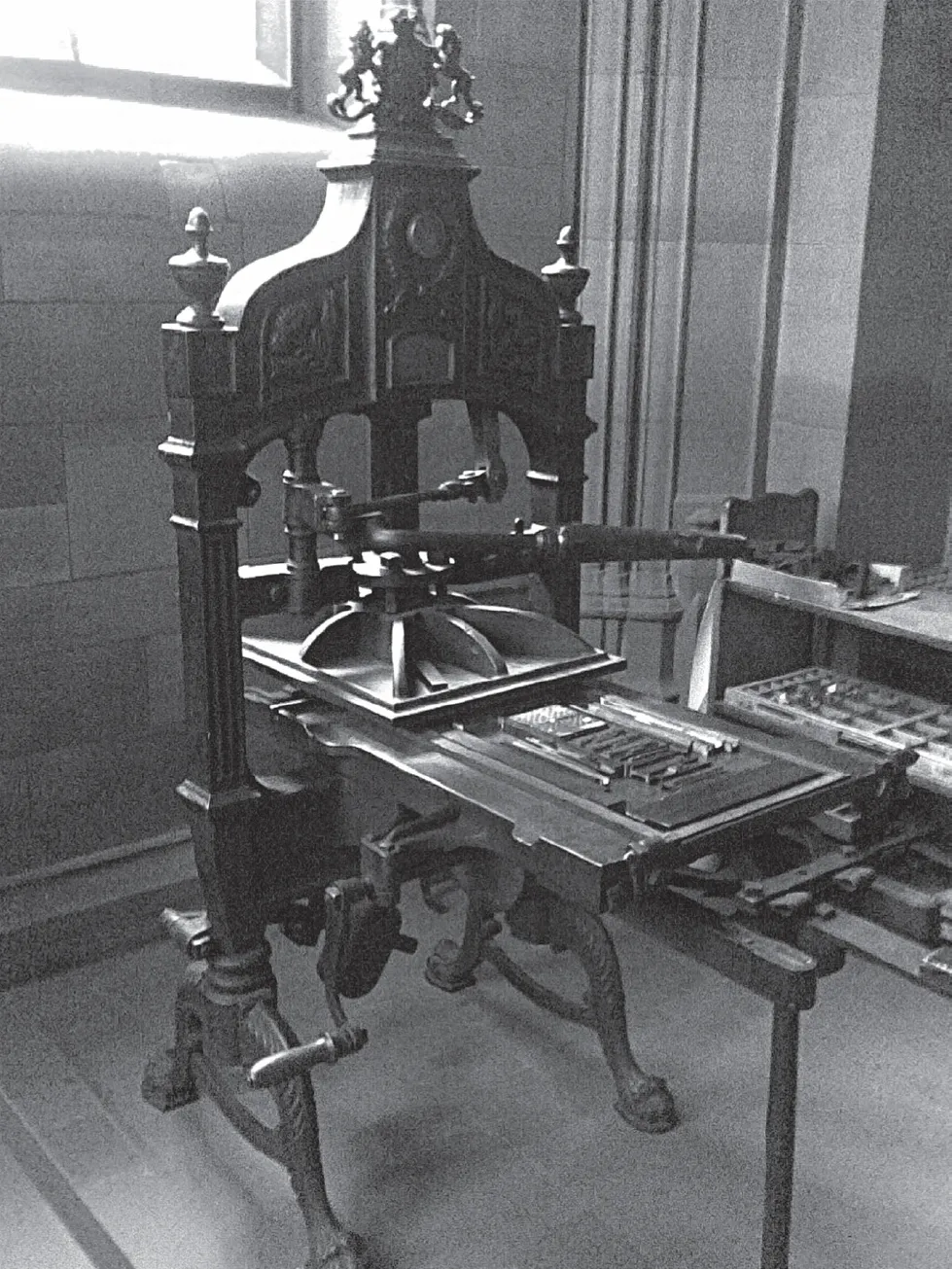

A Printing Press. (Author’s Collection)

Most eighteenth century newspapers began as irregular publications, starting out as a large sheet or two that was printed once, or perhaps twice, a week when there enough new material to fill the page. Of all the titles published, only a few prospered. Many survived for just a short period, mainly because they did not make money for their owner. Some were set up to campaign on a particular topic and faded away or amalgamated with another paper if their objective was achieved or became irrelevant. Others depended upon the drive and commitment of a key individual for getting each edition to press and struggled as soon as that person was no longer involved. Amongst all the national papers that were printed, a few stand out for their high quality reporting or because they appealed to a wide section of the populace. These are likely to be used extensively be researchers.

The Morning Chronicle

The Morning Chronicle was founded in 1769, and gradually became associated with the Whig Party, a progressive group that was most likely to listen favourably to calls for political or social reform. It provides valuable insight into the practicalities of disseminating news stories and advocating change in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries. In the mid-nineteenth century when official attitudes had become more relaxed it employed some notable, reformist contributors including the writer Charles Dickens and political philosopher John Stuart Mill. It also commissioned some very authoritative studies into what life was really like for the poor. After Stamp Duty on newspapers was abolished in 1855, newspapers that catered for a range of tastes and interests developed and probably drew some readers away. The final edition of the Morning Chronicle was published in 1865, though its publication had been intermittent for a couple of years before that.

The Morning Post

The Morning Post was first published in 1772. Initially, it was supportive of the emerging Whig Party but within a generation it was promoting moderate Tory views. In the early-nineteenth century it was a rival to the more progressive Morning Chronicle, attracting contributors such as William Wordsworth and Charles Lamb. After 1855, The Morning Post adapted successfully to the more crowded market-place, establishing itself as a supporter of conservatism in public life. It continued to publish until 1937 when it was taken over by the Daily Telegraph, which was serving the same readership.

The Times

The Times was founded in 1785, as the Universal Daily Register, by John Walter to advertise a new printing system for which he held the patent. It changed its name in 1788. Initially a four page newspaper, it carried a mixture of advertising, commercial, political and military news and notices and some reports from the law courts.

The Times developed its formidable reputation for quality journalism in the first half of the nineteenth century under editors Thomas Barnes (1817-41) and his successor John Delane (1841-77). The two men believed that a newspaper should be free both to report the truth and to comment on it. As official attitudes became more tolerant these editors did so on many occasions, earning The Times the reputation of being Britain’s most influential newspaper and its nickname, The Thunderer.

The Times is regarded as the newspaper of record and is an indispensable source when researching major national events and issues of social concern, though it should never be treated uncritically. Although it has usually maintained an independent stance rather than taking a political line, it was less likely to champion change than some other publications and there are periods when it seems to be promoting an official viewpoint rather than providing a truly independent analysis. There are also instances where the newspaper had formed a firm opinion and where the coverage may have been designed to steer readers towards this view rather than representing the actual position.

The Guardian

Several regions of the country had a serious newspaper that concentrated on economic and social issues in the area’s largest town and its hinterland. The Manchester Guardian was the one which made the transition from a provincial to a national English newspaper. It was established as a weekly publication in 1821 and began to publish daily in 1855 after the removal of Stamp Duty. It changed its name to The Guardian in 1959 and only moved from its Manchester roots to London in the 1960s.

The Manchester Guardian developed as a newspaper of significance under the long editorship of Charles Prestwich Scott (1871-1928) who demanded high quality writing, accuracy in reporting and a balanced approach, believing that ‘comment is free but the facts are sacred’. During his editorship the paper stepped into the reformist void left by The Morning Chronicle when it ceased publication in 1865. Unlike other national newspapers which tended to promote the status quo, The Guardian was prepared to discuss unpopular or controversial causes, present minority views and report dissent.

The Guardian is an excellent resource for researchers for two reasons. Its willingness to reflect anti-establishment attitudes shows that society was often much less unified than other newspapers may indicate. It is also a very good place to find material relating to the north of England, an important industrial area in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The Daily Telegraph

The Daily Telegraph was first published in 1855 as The Daily Telegraph and Courier. Although it positioned itself as a reformist publication, it differed from other national newspapers in that politics and reform was not one of its main interests. It covered political news but included other unrelated subjects such as science, business and fashion. It also carved out a niche promoting and sometimes raising funds for public and charitable causes.

The success of The Daily Telegraph and Courier in establishing itself in a competitive market demonstrates that politics was not an all-consuming passion of the literate public, even those who were politically aware. It perhaps explains why the more campaigning Morning Chronicle began to struggle when readers had a greater choice of newspaper content.

In 1937, The Daily Telegraph bought one of its competitors for the same market share, The Morning Post. The resultant publication was the conservatively-minded Daily Telegraph.

Technical and Social Developments

Although the reduction of Stamp Duty was important to the development of printed news, it was just one of several factors that helped British newspapers grow from a few weekly or bi-weekly publications, which targeted a narrow section of society, into daily editions, produced on an industrial scale and catering for a diverse and voracious readership. By 1840, a combination of increased scientific knowledge and the ability to translate this new understanding into practical applications, had speeded up the news-gathering, printing and distribution processes.

Until the development of the electric telegraph system in the 1830s, journalists had to deliver their copy to an editor via a slow and unreliable postal system. Stories could take several days to make their way into print, perhaps even after a rival newspaper had already broken the news. As telegraph offices began to open in large and small towns throughout the country, reporters could have their material transmitted back to the office within hours, giving editors of successful papers enough news to justify printing daily editions of their paper. Around the same time, the postal service became more regular and reliable, allowing reports and sketches to be posted to a newspaper office with confidence that delivery would be speedy.

By the mid-nineteenth century, production technology was innovating rapidly. Simultaneous printing on both sides of a sheet of paper, automatic paper feeds from large rolls, machine cutting and automatic folding of pages all became the norm, enabling newspapers to be produced quickly and in quantity. The machinery that made all this possible demanded a substantial amount of capital and newspaper proprietors who made a heavy investment in plant and premises wanted to recoup their outlay as quickly as possible rather than have expensive equipment standing idle. Speedy distribution of each edition across the country became ever more practical as the new railway network linked cities, towns and villages together. All of these technical developments cumulatively made daily editions of popular newspapers a sound business proposition.

Meanwhile, the number of customers was growing by the decade. By the time Stamp Duty was finally abolished, Britain had shaken off the privations of the ‘hungry forties’, a decade of severe economic hardship, and was entering a period of prosperity. Better understanding of how diseases spread resulted in sanitary reforms which gradually produced longer life-expectancy. A gradual reduction in child mortality, initially amongst the better-off, but eventually across all classes, also contributed to a noticeable increase in the population.

A prospering economy meant that new business opportunities opened up a range of technical, office and shop-based roles and a supply of literate workers was needed to fill them. In 1870, elementary education became compulsory for all children which, over a few decades, led to increased literacy amongst adults from the less affluent classes. By the 1880s, advances in shipping and refrigeration enabled Britain’s wholesalers to import cheap food in bulk from around the world. Prices in the shops began to fall, which meant that the weekly wage stretched further and gave even manual workers a little discretionary spending power. All of this created the conditions for the further expansion of the newspaper industry.

Mass Market Newspapers

As the nineteenth century drew to a close, there was a readership whose needs were not being catered for by the established daily newspapers. Lower-middle class and working class people did not always have strong enough reading skills to cope with lo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: A Brief History of Newspapers in Britain

- Chapter 2: The News Chain

- Chapter 3: Content of a Newspaper

- Chapter 4: Factors affecting Newspaper Research

- Chapter 5: Issues that affect all Types of Source

- Chapter 6: Preparing to Research

- Chapter 7: Which Newspapers to Start With?

- Chapter 8: Finding Material in On-line Newspapers

- Chapter 9: Historical Studies using Old Newspapers

- Chapter 10: Some Data Handling Techniques

- Chapter 11: Data Handling using a Spreadsheet

- Chapter 12: Using Spreadsheets in a Historical Study

- Chapter 13: Illustrations in Newspapers

- Chapter 14: Using Newspapers with other Sources

- A Study in Slander

- Research from Newspaper Sources

- Appendix 1: Accessing Old Newspapers

- Appendix 2: Worldwide Newspaper Websites

- Appendix 3: Other Websites for Researchers

- Appendix 4: Money, Weights and Measures

- Appendix 5: Publicising Results

- Glossary

- Further Reading

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Historical Research Using British Newspapers by Denise Bates in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.