- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This beautifully illustrated history of miniature ship models features hundreds of color photographs of some of the finest miniature ships ever built.

In this informative book, model expert Paul Jacobs traces the history of modern models back to their use as identification aids by the military in World War I. Miniature Ship Models is the first serious history of the industry's development, the commercial rise and fall of companies, and the advancing technology that produced ever more detailed and accurate replicas.

Writing with collectors in mind, Jacobs looks at the products of each manufacturer, past and present, rating their quality and suggesting why some are more collectible than others. Jacobs also addresses subjects of interest to model makers, such as painting, modifying and diorama settings. Illustrated throughout with many of the finest examples of the genre, the combination of fascinating background information with stunning visual presentation will make this book irresistible to any collector or enthusiast.

In this informative book, model expert Paul Jacobs traces the history of modern models back to their use as identification aids by the military in World War I. Miniature Ship Models is the first serious history of the industry's development, the commercial rise and fall of companies, and the advancing technology that produced ever more detailed and accurate replicas.

Writing with collectors in mind, Jacobs looks at the products of each manufacturer, past and present, rating their quality and suggesting why some are more collectible than others. Jacobs also addresses subjects of interest to model makers, such as painting, modifying and diorama settings. Illustrated throughout with many of the finest examples of the genre, the combination of fascinating background information with stunning visual presentation will make this book irresistible to any collector or enthusiast.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Miniature Ship Models by Paul Jacobs in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Seaforth PublishingYear

2020eBook ISBN

9781783830039Subtopic

Military & Maritime HistoryTHE BIRTH OF

1:1200 SCALE MODELS

1900-1919

1:1200 SCALE MODELS

1900-1919

WAR GAMES

IN 1913 H G WELLS, who is best remembered for his great science fiction novels, published a small book called Little Wars. Although the word ‘Little’ referred to war games fought with miniature soldiers, the nature of the wars described inside clearly harked back to the latter half of the nineteenth century. Photographs of the staged battles show small groups of infantry, cavalry and artillery, often in miniature tropical settings. Wells’ book was really a summary of the war-gaming that he and other literary contemporaries like G K Chesterton and Robert Louis Stevenson had created and played for years. It is ironic that the book appeared only a year before the outbreak of one of the biggest, most destructive wars in history, but also because it had none of the trappings of the modern wars with tanks and airplanes that Wells himself had foreseen in his prescient writings of the prior decade.

While Little Wars dealt with land battles, there had already been games and rules created for naval battles. The earliest recorded use of ship models in war-gaming is found in John Clerk’s Essay on Naval Tactics, published in 1782. Clerk and a friend attempted to recreate historic battles using small model ships. The exact nature of these models is not recorded, but they must have been quite small, as Clerk indicated that ‘every table’ afforded sufficient space for comfortable manoeuvres. Aside from Clerk, there are no other recorded instances of model ships being used in such activities until nearly one hundred years later.

In the 1870s the Germans developed Kriegspiel, a professional form of war-gaming, using rules to govern play and to simulate battles. By the 1890s it was in widespread use in various forms at military colleges and at staff levels. With the availability of inexpensive lead soldiers it was also being played by civilian adults and children. The original rules were created for land battles, but rules for naval battles were developed and games held.

There were also innovators of Kriegspiel in the United States. In 1882 Army Major William Livermore introduced an American version and soon made the acquaintance of William McCarty Little, who had retired from the Navy in 1876. Little lived in Newport, Rhode Island, and was instrumental in introducing war-gaming into the new Naval War College which opened there in 1884. Using the methods developed by Little, Livermore, and the German military, the War College held its first games in 1887. Soon these games developed into an annual event, so important and popular that when Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt prepared to visit, he asked to spend time observing one of the games.

Games at the Naval War College were staged in a large hall with a tile floor marked off in grids. The arrangements over time became quite elaborate. Each grid, eight inches square, represented a sea mile. There were always two teams, kept separated at all times. A screen was placed in the centre of the hall and removed only when the opposing forces had come within scale visual distance of each other. There were umpires, plotting tables, instruments for measuring distances and angles, cards with statistical information, and ships. What sort of ships? The ships could not be called ship models. Instead, they were small lead markers, made in three sizes, the largest of which was less than an inch in length. They could be joined together with metal strips to form squadrons which could then be manoeuvred into battle.

These games were critical to the mission of the college. In 1909 retired Rear Admiral Stephen B Luce, who had been the first president of the college but subsequently became a faculty member, emphasised the importance of the war game, stating that the manoeuvring of ‘miniature’ fleets on the tactical board was vital to learning to command fleets at sea.

FREDERICK T JANE

As would be expected, it was not only in Germany and the United States that naval war games were being developed and played. Britons also embraced war-gaming and it was in England that the first commercially made small-scale waterline models were used in war-gaming.

In 1873, an officer in the Royal Navy developed rules for a naval war game, to be used in training officers in tactics. Several other games were developed by naval officers in the succeeding two decades, but in general little official interest was shown in the Royal Navy for such training devices during that period, since a spotlessly painted ship seemed a better road to promotion in the peacetime Victorian service. Nevertheless, by the early 1890s, war games of various sorts could be found in the wardrooms of many British ships.

In 1898 Fred T Jane created ‘The Jane Naval War Game’. Jane, who had gained notoriety with his first annual Jane’s Fighting Ships published that same year, had taken up naval war-gaming in the early 1890s. As a correspondent and naval artist, Jane had the opportunity to spend time aboard both Royal Navy and foreign warships, where, in the wardrooms, he and the ships’ officers discussed the factors that gradually developed into the rules that would become the basis for his game. Jane then tested these rules in a series of games with friends. Over time, he discovered what worked and what did not. Some game rules proved to be too cumbersome, requiring too much time to play, involving excessive complication or too many umpires. In 1901 Jane published the book Hints on Playing the Jane Naval War Game. The book not only set out elaborate and sophisticated rules, but also discussed the manner of play, including a description of a lengthy campaign that he and some colleagues had carried out from March through May of 1900 involving seventy-five players. The group published ‘intelligence reports’ daily in the local newspaper, and took into account weather, coal consumption, mechanical breakdowns, false intelligence, logistics, and numerous other factors.

Soon, full-page advertisements for the game ‘invented by Fred T Jane’ began to appear in Jane’s Fighting Ships and continued annually in each edition. The 1904 edition, for example, promotes in block letters ‘THE JANE NAVAL WAR GAME,’ followed by ‘(Naval Kriegspiel Copyright)’ and ‘For the Solution of all Tactical and Strategical Problems’. It then goes on to state that sets of twelve model ships start at three pounds, three shillings and up. The more expensive the set, the more ships were included. This is what distinguished Jane’s game from all its predecessors: the ship models. None of the other games that had been developed used recognisable replicas of ships. This was the critical difference that made his game relevant to the future of waterline ship modelling: the ships were miniature replicas of the real things. The advertisement goes on to claim ‘Every Typical Warship in the World is now to be had in the Naval Game. New ships recently added include Kashima, Black Prince, Gambetta, K P Tavritchesky, Washington, Variag, Louisiana, Arkansas, Prinz Adalbert.’ In succeeding annuals, the names of more new ships appeared each year. Furthermore, the rules were changed and updated, usually in the annuals. Later advertisements boasted, ‘Officially adopted in nearly every navy in the world.’ The Jane’s annuals were actually laid out in such a manner as to complement the games, providing information specifically intended to be used with the game.

Since the least expensive version of the game cost the equivalent of about two weeks’ wages and required a table ‘not less than ten feet by eight feet’, it was never popular except among professional naval officers, who played it at the war colleges, and civilian adults who were connected in some way with the naval establishment.

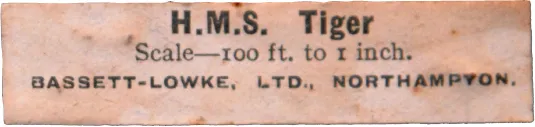

Typical Bassett-Lowke label.

HMS Tiger by Bassett-Lowke. This model is typical of those made during World War I.

In 1912 the final set of rules appeared. It was 91 pages long and updated to include submarine warfare, balloons and aircraft. Sampson, Low, Marston & Company, the publishers of both the game and Fighting Ships, was producing models of nearly all the world’s major warships: all waterline and all to the same scale.

Describing the game, The Strand magazine reported in 1904 that the ship models were the ‘most accurate representations of actual ships’. They were, however, quite crude by today’s standards. Made of wood, with wire masts and guns, it is likely that these models were on a scale of 1 inch to 1800 inches (1 inch = 150 feet), smaller than the waterline models of this book, but large enough to discern the important features. However, it was not long before Sampson, Low turned to die-cast metal models, produced by companies such as the Brighton Manufacturing Company, which was experienced in casting lead soldiers. These models were hollow cast – that is, the inside was completely open – and not very well finished, but they were nicely painted, and represented all the major warships from battleships to torpedo boats. By the standards of even those days, they could hardly be called models. They were actually toy-like, although, unlike typical toys of any era, they did represent specific ships, and one could distinguish an Ajax from an Iron Duke or a Lion from an Invincible. Companies like Brighton marketed similar models as toys, separately from those supplied to Sampson, Low for the naval war game.

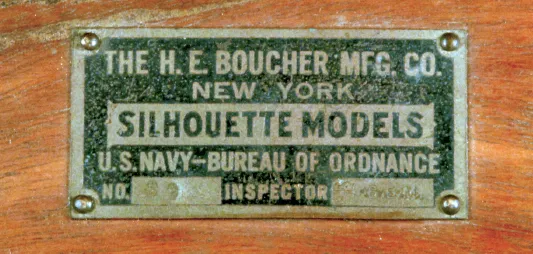

Boucher models of German ships in their wood box

BRYAN BROWN COLLECTION

BRYAN BROWN COLLECTION

Close-up of Boucher models of German dreadnoughts in their wood box

BRYAN BROWN COLLECTION

BRYAN BROWN COLLECTION

Label for Boucher set of German identification models

Production of the game ceased during the First World War, and was not resumed thereafter, perhaps a victim of the anti-war sentiment that swept much of the world after the unprecedented horrors and devastation of the war. Perhaps it was a victim of the disappointing results at Jutland and the failure of the navies as a whole to produce decisive battles like those at the Yalu in 1894, Santiago in 1898, and Tsushima in 1905. Or perhaps it was because of Jane’s death in March 1916, at the age of 51.

BASSETT-LOWKE

In 1898, at the same time that Jane was publishing his first annual and creating his war game, the firm of Bassett-Lowke was founded in Northampton, England. It was the outgrowth of another firm, J T Lowke & Sons, which manufactured castings and steam fittings for model makers. Bassett-Lowke at first focused on producing model railway engines, rolling stock, and miniature steam engines, but after a time the firm began to turn out ship models. These models were mainly full-hull working models and high-quality display and museum models, made of wood with lead, tin and brass fittings. In the early 1900s the company also began manufacturing small, very crude, wood-and-wire waterline models, perhaps for use in the Jane war game.

In 1908 Edward W Hobbs, a model ship and boat builder, joined Bassett-Lowke as manager of its new retail shop in London. Hobbs initiated a program to build constant-scale waterline models for the firm. He studied the available models, looking for a scale that would allow for good details but at the same time would allow a collector to assemble and store a reasonably sized fleet. Hobbs must have been familiar with the 1:1800 scale models that were being produced for the Jane war game, as well as others being made in larger scales. He could see the limitations of 1:1800 scale in terms of the amount of detail that could be shown, as well as the difficulty encountered in building them in wood. The simplest route would be to pick a size that was easily converted from feet into inches, which was the standard of measure in the British Empire and the United States, also known as Imperial Measure (as opposed to metrics). The easiest conversions were even numbers, 1:1200 (1 inch to 100 feet), or 1:600 (1 inch to 50 feet). The obvious choice was 1 inch to 1200 inches, or 1 inch = 100 feet, because it was easiest for model makers to convert plans and data, and make measurements for model making. Hobbs then contracted with a small company to produce some of these models. So began the first sustained manufacture of 1:1200 scale waterline models.

In addition to the 1:1200 models, Bassett-Lowke continued to produce models in any scale or size for which it could find a market. Large models, usually full hull, and working models, continued to be produced by custom order, whereas the small ones were made for general sales. While the company produced increasing numbers of 1:1200 models in wood, it also produced wood and lead waterline models in 1:1800 scale.

In 1911 the Admiralty contracted with Bassett-Lowke to produce models in 1:1200 scale for use in identification and gunnery training. By this date, long-range gunnery training had become standard. Spotting and identification of the target at long distance had become more difficult and critical. These models were not made for war-gaming, although undoubtedly after the First World War ended many of them fell into the hands of civilian war-gamers. The models were made of wood, with wire masts, cast metal main battery turrets, and funnels made from metal tubing. On ships with large-calibre turret mounted guns, turrets were affixed with a short nail, and could be turned. Several thousand models were made before production ceased in 1919.

Affixed to the underside of the model, an important artefact identified the producer, and remains today the best means of identifying most of these models. This took the form of a printed white label, about two inches long, with the name of the ship in bold letters and the words ‘Bassett-Lowke, Ltd., Northampton, Scale-100 ft. to 1 inch’ printed in black lettering. Later labels simply had a blank space with a line where the ship’s name would be typed or hand written. These labels continued in use for all Bassett-Lowke 1:1200 scale models until the company ceased manufacturing in the 1950s.

While the Admiralty contract gave Bassett-Lo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Birth of 1:1200 Scale Models 1900-1919

- Chapter 2: Between the Wars 1919-1939

- Chapter 3: War! 1939-1945

- Chapter 4: The Post-War Era 1946-1960

- Chapter 5: Rebirth 1961-1965

- Chapter 6: Growth and Innovation 1966-1976

- Chapter 7: Into the Twenty-First Century 1977-2007

- Chapter 8: The Art of Collecting

- Chapter 9: Beyond Mere Collecting

- Conclusion

- Sources

- Appendix: List of Producers