![]()

1 FOUNDATIONS

ALTHOUGH throughout pre-Roman Britain, there were many individual tribes that made up the Britons, within the north west region the predominant tribe were the Brigantes. Their name means ‘hill dwellers’, which suggests that they built their settlements initially at least, within the Pennine region. Later, of course, they must have spread out to the lowlands, and, although there is no real evidence to support this opinion, I feel certain that the Brigantes must have established a settlement at the joining of the rivers Irwell and Medlock. It was, after all, an ideal defensive position, and that is why the Romans built their fort there years later.

Whether we can refer to the Roman fort as ‘the foundations of Manchester’ is questionable, but it is from this period that most people equate the origins of Manchester.

The Romans landed on the shores of Britain in AD43. And, although they managed to secure control of the south of the country, they found that moving northwards was somewhat more difficult. They made several failed attempts: Suetonius Paulinus, lead the legions north in around AD61, reaching as far as Deva (Chester), before being recalled to defend the south from further acts. They would return to the north west – Brigantia – over a decade later, finally reaching Manchester around AD79, after General Agricola marched the Twentieth Legion from Chester, across the wastelands of the north west (crossing the fords at Stretford and Trafford en route), to engage the Brigantes. This area, at the meeting of the rivers of Irk, Medlock and Irwell, was of such strategic value, that the Romans stayed and built an equally impressive fort here, at Manchester. This region, once so difficult to conquer, would later become one of the prime centres of activity by the Romans, with Manchester playing its part, along with that of Warrington, Wigan, Ribchester and Lancaster, of course.

![]()

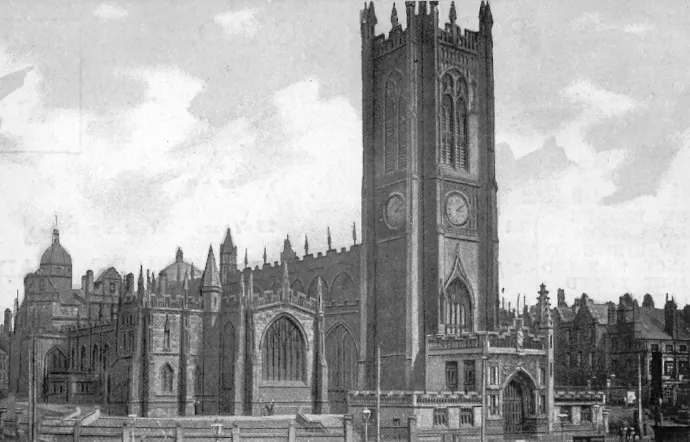

Manchester’s Cathedral stands on Hunt’s Bank, the location of the earliest of Manchester’s Roman forts which, according to Professor Charles Roeder, was built by Cerealis on one of his earlier expeditions into Brigantia. Author’s collection

![]()

The initial fortification at Manchester was made of local timber, and built on a natural raised mound, that gave the settlement its Roman name, Mamucium: meaning a ‘breast like hill’. The fort was quite substantial, covering around five acres and built to hold around five hundred men. Its location, at the meeting of the three rivers of Irwell, Medlock and Irk, held a strategic military importance as it protected the main route between the east and the west, across the Pennines, uniting Eboracum (York) to Deva. Sections of this Roman road can still be seen today: for instance, the causeway on the moors around Blackstone Edge formed sections of it.

Manchester’s fort was also used to control the natives, and defend the vital supply route through to the fort at Ribchester from attack. Between them, the two forts ensured that munitions, troops and supplies continued to flow northwards, to outposts such as Galacuim (Overborough) and Glannventa (Ravenglass) on the coast, and, most importantly, the outpost at Luguvalium (Carlisle), on the very edge of the frontier, to maintain the northern defences.

As the fort gained greater importance, within a few years of its creation, it was enlarged, and completely rebuilt in stone. And, throughout the Roman occupation the fort would continue to grow in overall stature, with further rebuilding and enlargements occurring during the Trajan and Hadrian periods.

Although the north west region was not as open to attack as the settlements situated further north, Manchester’s fort formed an important link in controlling the Brigantes; maintaining a strong and highly visible military presence meant that a rebellion was less likely and could be quelled quickly should it ever arise. Nevertheless, despite its stature, a posting here was not popular amongst the legionnaires, for in those times the north west region was largely wasteland, consisting of moors, marshland and bogs, the climate was cold and damp, and it was a most inhospitable place.

Every day life here at Manchester would be made that little bit more hospitable for the legionnaires and their families in AD84, when, on the instructions of General Agricola, a vicus (settlement) was created outside the fort. Although it was not particularly large, consisting of about six streets, each of them running off a central main thoroughfare, it was self-contained, with its own mill, and large enough to accommodate several families. Although this could easily be mistaken for the beginnings of Manchester, in reality it was far from it, for the vicus didn’t survive the Romans eventual departure; although in some ways it did form the foundations of Manchester, in that its stone, along with that of the fort, would be plundered and used to build the early town of Manchester in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

Despite the work carried out here at Mamucium, once the legions were recalled to Rome, in AD410, the region underwent a period of unrest, with various local tribes and groups fighting for supremacy, and the result was that the fort fell into disuse, and its stone plundered.

Manchester’s Roman Heritage

Throughout the centuries many travellers and writers of their day have visited the remains of what might well be described as Roman Manchester, though their views are often misleading. For instance, John Leland visited Manchester during the sixteenth century and was less than impressed with the remains of the old fort, claiming that much of it had already been plundered for building work elsewhere; however, two centuries later William Stukeley, visited Manchester and was impressed with what he saw.

Although the Roman fort at Manchester should be the pinnacle of the city’s historic heritage, sadly its not, for unlike Chester, Manchester’s passionate embrace of the industrial revolution caused massive damage to the Roman remains. Unfortunately, the eighteenth and nineteenth century’s desire for commerce would inflict severe, irrepairable damage to this historic site: the growth of the cotton mills lead to the introduction of vital transport links, such as the canals and the railways, whose construction, taking place right in the heart of Castlefields, almost obliterated the old fort site. But, if this wasn’t bad enough, further damage was to follow with the building of rows of terraced houses here in the latter years of the nineteenth century.

Despite this construction – and in some cases because of it – there have been many Roman artefacts discovered throughout the centuries: a bronze statuette of Jupiter was found here during the nineteenth century, and further excavations, in around and under Knott Mill Station, has revealed more of Manchester’s Roman fort, and helped archaeologists to understand more of its layout. In more recent times, there have been many attempts to uncover the lost settlement that was Roman Manchester. A section of the surrounding defensive ditch was discovered in 1951, and three years later, some of the former ramparts were unearthed off Beaufort Street, by Professor Atkinson of Manchester University. As part of the area’s heritage, part of the old ramparts have been skilfully reconstructed, including the North Gate and the West Wall, and now form part of the Castlefield Urban Heritage Park, which opened to visitors in 1982.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The later Roman fort was located at Castlefield in AD 79. It was an ideal defensive position shielded by the rivers Irk and Irwell. However, the arrival of transport during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – namely the canals and the railways – altered Castlefield so much that the remains of the Roman forts were all but destroyed. These three modern photos show the reconstructed remains of the fort, an example of what a section of the fort might have looked like, and the impact of the canals and railways. The Author

![]()

The Dark Ages

After the Roman’s departure, a minor settlement continued here made up of Romano-Britons, changing its name to Maineceastre: meaning simply ‘the place of the fort’. In AD429 the Picts and the Scots invaded, and laid waste to the area, including the settlement of Maineceastre. The local Britons, in what we can only conclude must have been sheer desperation, summoned the assistance of the noted warriors from Saxony, who were often used as mercenaries, to fight the barbarians. The Saxons defeated the Celts and thereafter took the land for themselves; tribes of Saxons, Angles and Jutes spread throughout the country, including Maineceastre, which they later renamed Manchester: meaning ‘men of the fort’.

Around this period, the Britons turned to new leaders to fight, and hopefully defeat the Saxons. From this undocumented period, stem many myths and legends of many victorious warriors, such as King Arthur, who is said to have lead many an army, in many decisive battles, against the Germanic invaders. These are nothing more than that; legends, myths, old-wives stories, and have little basis in history. Included in this is a tale often told of the settlement of Maineceastre concerning the fight that Sir Lancelot is said to have had with a giant Saxon knight, by the name of Sir Tarquin, who is supposed to have lived in the ruined Roman fort or castle on the banks of the River Medlock and had supposedly slain many knights. Sir Lancelot fought and killed Sir Tarquin, so the legend says, with the assistance of Vivian, the lady of the lake. However, despite this interesting little tale, there are no records to support it, and no record of a Saxon knight ever having lived in the ruins of the Roman fort.

Life Beyond The Dark Ages

The Anglo-Saxons divided England into seven kingdoms. Two of the largest – Mercia and Northumbria – were situated in the north. Manchester, initially at least, was contained within the borders of Northumbria, which had been created during the sixth century. Later, sometime between the seventh and ninth centuries, the borders of Mercia and Northumbria were altered: the southern border of Northumbria became the River Ribble, so south of the river became Mercia which, of course, included the castle at Manchester.

During this period, the settlement was growing in stature once more, as it is suspected that the town’s first church, dedicated to St Mary, was built around this time. And, although its location is not known for certain today, it is largely thought that it stood somewhere between the modern-day streets of St Mary and Deansgate. Again, its fate is not known for certain either, though it is thought that it was probably destroyed during the Viking invasion of the ninth century. Today the only remains are the famous Angel Stone, discovered during alterations to the cathedral in 1871.

The Vikings destroyed Manchester’s church, and wrecked the town, laying it and its inhabitants to waste in AD865. The Great Army of the Danes swept throughout the country, overrunning the former kingdoms of both Northumbria and Mercia and more besides. For years much of the north of England lay in the Vikings hands. And with their capital at York, they set about creating settlements within their new kingdom; there were several of these around Manchester, such as Oldham, Hulme, Cheadle Hulme and Urmston.

Resistance eventually came from the south, lead by Alfred, King of Wessex, who engaged the enemy in battle on several occasions, slowly but surely gaining victories. This fight was continued by his children, Edward the Elder and Aethelflaed, Queen of Mercia, who succeeded in forcing the invaders back across the border of the River Mersey. To protect this new boundary a series of defensive forts, or Burhs, were established along its length, at Chester, Eddisbury and Runcorn. Later, in AD923, King Edward established two new forts at Thelwall and Manchester, respectively. This attention to Manchester brought about its rejuvenation, and having a fort on its doorstep once more made it a safe place to settle. Edward’s conquest of Northumbria later that same year, finished the task in forcing the Danes to flee to their capital at York; although the final victory would be more than a decade later, in the Battle of Brunanburgh, won by his illegitimate son, Athelstan, that ended the wars once and for all.

Following the end of the conflict, Northumbria’s border was reestablished at the River Ribble, though Mercia’s northern border was re-drawn, this time further south, at the Mersey. The area in between was given separate status, as a Royal domain, though contained within the huge diocese of Lichfield (which it remained through to 1541). Manchester became a part of this Royal domain, referred to as Inter Ripam et Mersham: ‘the lands between the Ribble and the Mersey’.

The Danes invaded again in 1012, this time led by King Swein, who was successful, leading to the reign of the Danish kings of England: though the prize of the first Danish king of England was not to go to Swein, who was killed in battle just prior to their overall victory, but to his son Canute. King Canute ruled England with the inclusion and co-operation of the Saxon chiefs, making life for the common people basically unaltered. Later, however, the administration of the country, which had been greatly enhanced with the creation of the earldoms, once again subdivided into smaller areas known as Wapentakes (thought to originate from both Saxon and Norse terms for weapon count, an early form of voting) later becoming more commonly referred to as Hundreds, as each area contained one hundred manors. The land between the Ribble and the Mersey was divided into six such hundreds: West Derby, Blackburn, Leyland, Newton, Warrington and Salford: Manchester was contained within the latter, it was not able to form such a hundred itself, as it was still in a ruined state from the fighting with the Danes – Salford, on the other hand, holding less importance, had been less affected. The land between the Ribble and the Mersey was still under the direct control of the ruling monarch, and would remain so until the arrival of the Normans to our shores in 1066.

Norman England

The arrival of the Normans brought with it great changes to the way the country was administered. The former royal domain, the lands between the Ribble and the Mersey, was awarded to William’s cousin, Roger de Poitou, the youngest son of Roger of Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury. Roger was to prove a good administrator, establishing forts and castles throughout his territory, and appointing barons to control each of the sectors. At Manchester, for instance, a new castle was built, and further streets added to the medieval town.

The start of medieval Manchester saw the town being rebuilt in the area surrounding the old Roman vicus. This was referred to as Alport, meaning old town, wit...