- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"A wonderful book detailing the construction of the Royal Navy's sailing warships" from the maritime historian and author of

Nelson's Navy (

Pirates and Privateers).

The National Maritime Museum in Greenwich houses the largest collection of scale ship models in the world, many of which are official, contemporary artifacts made by the craftsmen of the navy or the shipbuilders themselves, and ranging from the mid-seventeenth century to the present day. As such they represent a three-dimensional archive of unique importance and authority. Treated as historical evidence, they offer more detail than even the best plans, and demonstrate exactly what the ships looked like in a way that even the finest marine painter could not achieve.

This book takes a selection of the best models to both describe and demonstrate the development of warship construction in all its complexity from the beginning of the 18th century to the end of wooden shipbuilding. For this purpose, it reproduces a large number of model photos, all in full color, and including many close-up and detail views. These are captioned in depth, but many are also annotated to focus attention on interesting or unusual features, which can be shown far more clearly than described. Although pictorial in emphasis, the book weaves the pictures into an authoritative text, producing an unusual and attractive form of technical history.

"This book includes plentiful visual representations of actual ships in model form and the accompanying graphics make for wonderful reading . . . I cannot express enough how enjoyable this book is to read."— Spotter Up

"A high-quality book which is recommended to all ship historians and modellers."— Military Modelling

The National Maritime Museum in Greenwich houses the largest collection of scale ship models in the world, many of which are official, contemporary artifacts made by the craftsmen of the navy or the shipbuilders themselves, and ranging from the mid-seventeenth century to the present day. As such they represent a three-dimensional archive of unique importance and authority. Treated as historical evidence, they offer more detail than even the best plans, and demonstrate exactly what the ships looked like in a way that even the finest marine painter could not achieve.

This book takes a selection of the best models to both describe and demonstrate the development of warship construction in all its complexity from the beginning of the 18th century to the end of wooden shipbuilding. For this purpose, it reproduces a large number of model photos, all in full color, and including many close-up and detail views. These are captioned in depth, but many are also annotated to focus attention on interesting or unusual features, which can be shown far more clearly than described. Although pictorial in emphasis, the book weaves the pictures into an authoritative text, producing an unusual and attractive form of technical history.

"This book includes plentiful visual representations of actual ships in model form and the accompanying graphics make for wonderful reading . . . I cannot express enough how enjoyable this book is to read."— Spotter Up

"A high-quality book which is recommended to all ship historians and modellers."— Military Modelling

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Wooden Warship Construction by Brian Lavery in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Seaforth PublishingYear

2020eBook ISBN

9781473894822Subtopic

Military & Maritime History1: Labour and Materials

THE SAILING WARSHIP

Nearly 1500 warships were built for the Royal Navy between 1715 and the end of the long wars with France a century later. In 1756–1815 alone, 261 of these were ships of the line, the largest warships of the day. They were practically all sailing warships – some of the smaller ones could be rowed as well, but only very inefficiently and slowly. even in the Mediterranean, the home of the galley, the type declined through the century – despite its manoeuvrability, it was no match for the robust hull and heavy gun power of the sailing warship. Only less regular navies, like the Barbary corsairs of North Africa, used chebecs, which could be rowed as well as sailed. Rowing was also used in coastal waters, for example by the Swedes in the Baltic, but the sturdy wooden sailing warships dominated the open seas.

The sailing warship was built almost entirely of wood, with iron for a few key fastenings and later copper on the underwater hull. Its main metallic parts were its guns which were essential to its purpose – the power of a warship was measured in its ‘weight of metal’ as much as anything else. But in most ships the great majority of guns could only be fired over the side, so a ship could produce little fire as it advanced towards an enemy, and not much more as it retreated. But the broadside power of a large or medium-sized warship was equal to that of a whole army or one of the largest fortresses on shore.

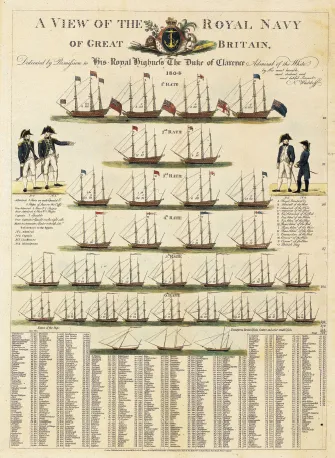

PAJ1758 A print showing most of the ship types used by the Royal Navy in 1804. It does not show the fore-andaft rigged and non-rated vessels fully, only a cutter, a schooner and a type of ketch which was obsolescent by that time. It also shows officers’ uniform and a selection of naval flags, including those normally used for launching on the First Rate at the top left, and Third Rates of the blue, red and white squadrons.

OTHER NAVIES

The warships of the other major naval powers – France, Spain, the Netherlands, Denmark, Portugal, Sweden, Russia and later the United States of America – were generally similar in concept to the British ones, with comparable methods of design and construction. Captured or occasionally purchased ships were transferred quite easily from one navy to another, with only superficial changes to the fitting and rigging. But at the same time each nation’s ships had their own individual characteristics. French ships were regarded as faster with finer lines, which fitted their need to make a quick getaway past the British blockades of their ports. British naval officers loved them, but dockyard officials deplored their lighter structure and need for more maintenance. When the great three-deck Commerce de Marseilles was captured at Toulon in 1794, her acting captain reported that she was ‘Very weatherly; few ships we were in company with were equal to her’ and that she ‘steers remarkably easy, never known to miss stays’. The officers of Plymouth Dockyard, on the other hand, proposed strengthening her by ‘shutting in the openings of the wales with fir 5 inches thick, the bottom with 4 inches and the topside with 3 inches, and to fur out the timbers to make good the different thicknesses, to bolt a few of the bends of riders in the hold, and to bolt the thickstuff through the side and beams in order to stiffen her, as she has no lodging knees’. In fact the ship was never used on active service.

SLR0556 The Eole was a French 74-gun ship of 1789. She was built to a standard design by Jacques-Noël Sané, as most French ships were by that time. She has a flatter sheer than British ships of the period, that is, her planks and wales had less upward curve.

Spain employed both British and French émigré shipwrights and evolved two schools, which were sometimes combined to produce some very fine ships. The Dutch had been the leading naval power in the seventeenth century but as ships got larger they were constrained by the need to give their ships shallow draught to enter their own ports. The Americans, arriving towards the end of the eighteenth century, mainly built medium-sized warships, frigates. They deployed the classic strategy of a small naval power, to make each ship as good as possible and raid enemy possessions and convoys. They were well-built with excellent timber and surprised the British in several frigate actions. The Russians, on the other hand, relied heavily on copying Western ships, including eight built to the lines of the famous HMS Victory, after her plans were stolen and copied. The Danes and Swedes also learned from Britain and France, sending out apprentice shipwrights to these countries and often collecting plans on the way. But Sweden produced one of the most innovative naval architects of the age in Fredrik Henrik af Chapman, who designed various types of gunboats for use in the Baltic.

SLR0591 A model of the Dutch 74-gun ship Washington of 1797, showing something of the flat bottoms which the Dutch were compelled to use to get into their own waters. The model is to an unusual scale and came with masts, spars etc which were never assembled.

SLR0405 The model of a 50-gun ship of around 1715 which is the starting point for this work. This photograph shows the starboard side which has the modern features – cant frames in the bow, overlapping futtocks and solid lower wales – all of which are explained later. However, it does not show the final form of the changes: the framing above the lower wales would be much more solid in later ships.

BRITISH SHIPS

If most navies produced relatively specialised designs for their own strategic and tactical needs, the British aimed at world power and deployed more generalised ships. They had to be robust to travel the planet in all weathers, and to stay at sea while blockading the enemy in port. Therefore a strong structure (rather than speed) was a vital factor in British naval success, and in building and maintaining an empire and in protecting British trade which fuelled the Industrial Revolution.

The starting point of this work is 1715, when the Navy Board issued new orders about the building of ships. By that time the English Royal Navy (‘British’ since the union with Scotland in 1707) had fought three wars with the Dutch and two with the French in the last sixty-three years. It had developed the line of battle at the beginning of that period, with all the major warships fighting in a single line of up to 100 vessels, and which would define tactics and shipbuilding for most of the eighteenth century. After 1715 it had a period of relative peace and consolidation, and often ultra-conservatism about ship design and all other matters.

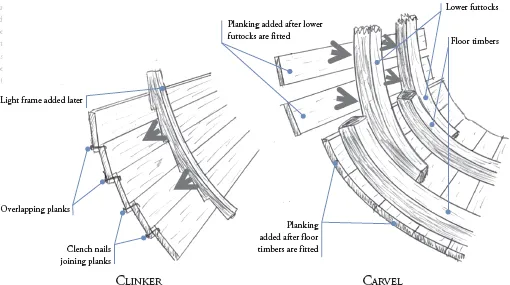

The main building technique of the time was ‘carvel-build’. It was often described as ‘frame-first’ construction in that the frames or ribs were erected then the ‘skin’ or planking was put over them. It contrasted with the technique of ‘skin-first’ or clinkerbuild in which the planks overlapped and formed an important part of the structure, with light frames added later. Carvel-build was the only possibility with such large ships: Henry V’s attempt to build a large triple-skin clinker ship, the Grace Dieu in 1418, was not repeated. But as with many things of the period, ‘frame-first’ was never as simple as the term suggests. We cannot assume that the whole frame was complete before any planking was put on, it was not unknown to begin planking of the lower parts before the toptimbers were complete, and much depended on the availability of materials.

SHIPYARDS

Shipyards were relatively simple in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, needing little capital equipment. The main requirement was a site on a firm bank close to a river which was deep enough for launching the ship on a suitable high tide. The slip was angled down towards the river, and could simply be dug out, or more commonly reinforced by timber or stonework. Man-powered cranes were needed for unloading timber, plus a considerable amount of space to store it. There might be a few workshops, but despite the weather the great majority of the work was done in the open air. Some kind of office was needed if only to examine and interpret the ship’s plans, with a larger and well-lighted loft where full-size moulds for the timbers could be drawn out. Sawpits were dug in the ground for cutting large trees and timbers.

Ships built in private yards were covered by extensive contracts. On 17 November 1755 Thomas West of Deptford signed a contract to build the 74-gun Warspite, of the new Dublin class, ‘agreeable to the draught that accompanies this contract, and to a 22-page specification.’ He also agreed,

I do oblige myself, in case the officers or overseers appointed by the said principal officers and commissioners to inspect the same, shall at any time find any defective or unsound materials, or insufficient workmanship performed to the said ship during her building, the said deficiency both in the one and the other shall, upon notice thereof, be forthwith amended, and the said officers or overseers shall not at any time have any molestation or obstruction.

The main differences between clinker building and the more modern form, carvel, are that the planks overlap in the former, and form the essential element in the structure. An early version of carvel building is shown on the right, with the futtocks of the frames not joined together. That is the system which was replaced from 1715 with pairs of futtocks each forming a single unit. (Author’s drawing)

Buckler’s Hard shipyard on the Beaulieu River in Hampshire, a relatively modern model made by Gerald Wingrove in 1968–9 but based on solid research. It shows the frigate Euryalus about to be launched in 1803, with the 74-gun Swiftsure in frame. The village is dominated by piles of timber in the streets and gardens. The end of the terrace on the right has the office from which the master shipwright, Henry Adams, kept an eye on the work. (Alamy Stock Photo)

The ship was to be built at the rate of £17 2s per ton for 1546 tons, any excess on that was not to be paid for. The first instalment of £2900 would be paid on signing the contract, the same amount when the keel was laid, stem and stern posts up and the floors crossed; then when the full frames were raised, ‘set to rights, levelled and shored’. After that the fitting of the filling frames between the gunports earned another instalment, then when the main wales were wrought and fitted and the bottom planked. The fitting of the gundeck beams earned another £2900, followed by the upper deck, quarterdeck and forecastle beams and planks. The works in the hold and the main channels ear...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Copyright

- Contents

- 1: LABOUR AND MATERIALS

- 2: STARTING THE SHIP

- 3: FRAMES

- 4: OUTSIDE PLANKING

- 5: INSIDE THE HULL

- 6: FITTINGS

- 7: IN THE WATER

- APPENDIX

- FURTHER READING