![]()

CHAPTER 1 A Family Affair WHEN REGIONALIST PAINTER Rudolph Ingerle (1879–1950) set out in search of authentic American subjects in the late 1920s, he traveled from his home in Illinois to Indiana and Missouri, and was excited to encounter folks he declared “the salt of the earth” in the Smoky Mountains of Tennessee. His eponymous picture of a rustic couple posed in front of their house (Fig. 1.1), the man wearing overalls and the woman in kerchief and apron, proved a popular success throughout the 1930s. At the Art Institute of Chicago, when it shared the limelight with Grant Wood’s contemporaneous masterpiece, American Gothic (1930, Fig. 1.2), the paintings’ many similarities were not lost on appreciative critics. With their somewhat tattered clothes and furrowed brows, Ingerle’s couple bear signs of a hard life, yet the large sack of apples that spills open on the porch of their log cabin implies a bountiful harvest and the Edenic locale the artist indeed called paradise. The shiny red apples—one cradled emblematically in the man’s hands—also account for the knife held sharply erect by the woman, who will set about peeling them once her posing is done. Ingerle thus added a bit of narrative to his study of a type he exalted unequivocally as “the grandest people in the world, the finest Americans in the country.”1 He conveyed their upright character by means of their postures, echoed in the emphatic verticals of the planks and post that frame them, and in their facial expressions: the man appears affable, open and direct, while the woman, with her firmly set jaw and unflinching gaze, exudes capability, strength, and determination.

Fig. 1.1. Rudolph Ingerle, Salt of the Earth, 1930.

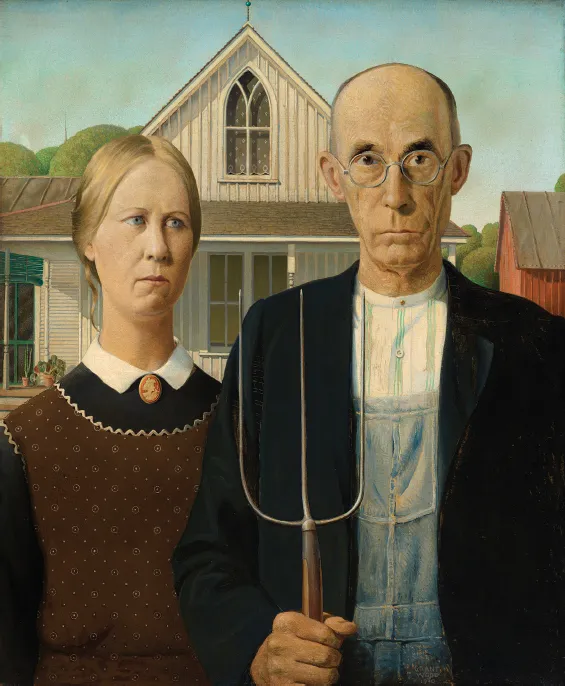

Wood, too, strove in his signature painting to assert a kind of regional character, presenting an anonymous couple, their homestead, a glimpse of their natural surroundings, and objects suggesting their industrious nature—pitchfork and well tended house plants. Yet how to account for the wildly incommensurate cultural fates of these two images, which share so much and which emerged, albeit independently, at the exact same historical moment? American Gothic quickly outstripped Salt of the Earth in popularity, achieving iconic status and bringing its artist immediate national renown while Ingerle continued to labor in relative obscurity. Why? Though formal differences between the paintings may offer only a partial answer, they do provide a starting point for analysis. Stylistically, Wood departed in American Gothic from the agreeable naturalism Ingerle practiced in favor of a fussier, almost hallucinatory verism, all forms crisply delineated, even down to the distant treetops. Wood, moreover, presented his figures quite confrontationally in the very foreground of the painting, giving them a looming presence and a corporeal breadth that exceeds the limits of his panel; Ingerle’s couple seems positively retiring in comparison with their aggressively positioned Iowa counterparts.

Further, while Ingerle offered viewers a toehold into a three-dimensional space by means of a strip of dry earth at the bottom of his picture, Wood erected a fourth wall so to speak, and, as James Dennis observed, handled pictorial space “like the successive layers of scenery on the stage.”2 Thus, in American Gothic, three painted flats, each parallel to the picture plane, construct a theatrical space: figures define a foreground, house and barn the middleground, and foliage and church steeple the background. In this way, Wood established an engaging dialectic between surface and depth, an effect enhanced by the repeating verticals of tines, seams, stripes, posts, and battens, which mark off degrees of recession in space while also, as a pattern, collapsing it. Despite his believably three-dimensional treatment of the heads and hand of the man and woman, the figures themselves are curiously flat, unlike Ingerle’s seated couple, whose knees jut forward, and whose bodies cast shadows and make physical contact with each other. Wood’s figures merely overlap, like cutouts placed one before the other.

The formal tension Wood set up between two and three dimensions constitutes just one of the many ambivalences informing American Gothic. On the level of subject matter, confusion has always reigned over the identity of the figures and their relationship to each other. Ingerle’s mountain folk seem completely believable as husband and wife, but not so Wood’s peculiar characters, with their troubling May–December age disparity. For decades after his demise, Wood’s sister, Nan Wood Graham, objected far and wide to the interpretation of these figures as a married couple, insisting that they were meant to represent small-town folk rather than farmers and that the woman “is supposed to be the man’s daughter, not his wife.”3 Although Graham modeled for the female figure in the painting and felt she had a direct line to the artist’s intentions, her claim resolves nothing and only thickens the plot, leaving us to puzzle over the whereabouts of the intimidating pitchfork man’s absent spouse and the nature of this strange household. “What kind of family is this?” demanded John Seery in his unsparing interrogation of everything gothic in American Gothic, indecorously inquiring “whether the spinster daughter acts as a wifely substitute, out there on the isolated plains, in more than merely housekeeping ways?”4

Fig. 1.2. Grant Wood, American Gothic, 1930.

In such speculations, the disturbing mysteries of the nineteenth-century gothic novel begin to come to the fore, along with “the hideous darkness of existence on the farms and in the hamlets” explored by Ruth Suckow, Wood’s contemporary in Regionalist literature.5 Unlike the Vienna-born, Chicago-based Ingerle who approached his regional types in Salt of the Earth with the detachment of an outside observer, Wood painted as Suckow wrote, from the perspective of a native Iowan. He was an uneasy insider, however, and his relationship to the puritanical, buttoned-up Midwesterners he presented in American Gothic was as much problematic as it was intimate and profound. Issuing from deeply mixed feelings, the painting is riddled with irreducible ambiguities, its ostensibly realist style at odds with its fundamentally obscure content. Is it, after all, paean or parody? Either way, the image possesses an affective power, subliminally registered by viewers but perhaps nervously covered over in the spirited humor of the picture’s endless, mocking iterations. Something about Wood’s curious characters may hit close to home.

Fig. 1.3. Hattie Weaver Wood, c. 1930.

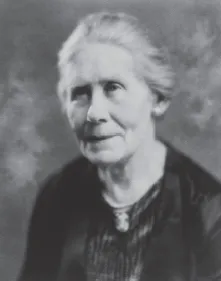

PORTRAIT OF MOTHER

As model for the daughter/wife, Graham was a convenient surrogate for the woman I believe Wood truly wished to depict in American Gothic—his mother, Hattie Weaver Wood (Fig. 1.3), modest helpmeet to Francis Maryville Wood, the artist’s farmer-father who had died of a heart attack in 1901. Grant, the couple’s middle son, was ten years old at the time of this sudden loss, and he felt it painfully ever after. Late in life, when asked about the stalwart couple in his famous painting, Wood declared them “tintypes from my own family album.”6 Among the various assertions he made about American Gothic, this one seems to me the most pointedly personal, the closest he ever came to admitting the picture’s private meaning or at least to bringing that meaning to consciousness: while not portrait likenesses, his figures suggest parental imagoes. Even in 1930, they appeared anachronistic, shades from long ago, as Wood dressed them up in clothing his parents would have worn when he was a child. In preparation for the painting, he asked Graham to make an apron edged with rickrack, an old-fashioned embellishment no longer readily available in local stores. She resorted to ripping some trim off of mother Hattie’s old dresses.7 Similarly, the man’s shirt in the painting, missing its detachable collar, was of a kind that had disappeared by the 1920s; Wood salvaged this example from the rag bin.

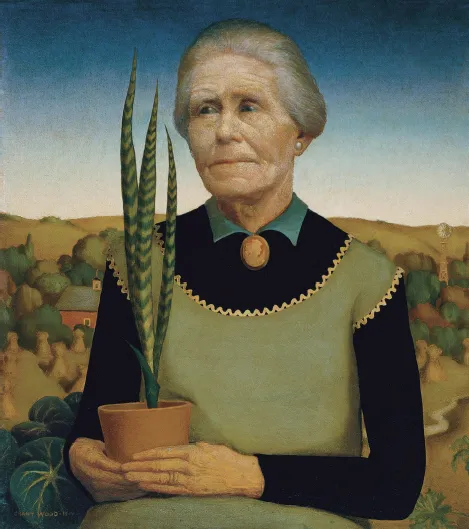

Fig. 1.4. Grant Wood, Woman with Plants, 1929.

If, in the spirit of authenticity, Ingerle based his picture on direct observation, Wood staged everything in American Gothic, creating a peculiar pastiche. His sitters posed in Cedar Rapids, but the house depicted was in Eldon. All details were carefully orchestrated and pieced together, the whole made seamless by Wood’s meticulously tidy brushwork, as in the secondary revision of a dream. Indeed, Wood’s entire process in creating this image could be described along an oneiric model, in which the secondary revision renders the dream coherent and credible by adding otherwise non-essential elements to fill in narrative gaps or leaps in logic in the dream’s often bizarre manifest content.8 Along with other psychic mechanisms that operate on the raw material of the dream (condensation, displacement, symbolization), secondary revision helps disguise the latent content of which the dreamer remains unaware. Wood combined the raw material of memories and of what was immediately at hand, just as dreams mix past experience with the fresh “day residue” of everyday life.9

Fig. 1.5. Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, c. 1503.

Woman with Plants (1929, Fig. 1.4), the artist’s tender portrait of his mother at age seventy-one, provided the direct prototype for the female figure in American Gothic. Among his earliest mature paintings, in which he incorporated stylistic lessons learned during a three-month trip to Germany in 1928,10 Wood depicted Hattie in front of an Iowa landscape at harvest time, complete with corn shocks, red barn, and windmill. Pressing his sitter up close to the picture plane, he provided her with a symbolic attribute, a potted sansevieria, in the manner of portraits by Northern Renaissance masters he had studied in Munich’s Alte Pinakothek. The tall plant suggests the authority within the family that passed to Hattie on the death of her husband; she holds it delicately, and its leaves number four, like her children, three boys and a girl. Wood’s placement of his seated halffigure against a faraway vista, omitting a middleground, brings Leonardo’s Mona Lisa (c. 1503, Fig. 1.5) inevitably to mind, and the addition of a little winding creek at the lower right of the composition strengthens this association. Through the generic titling of her portrait, Hattie achieves the archetypal status of a humble and hardy Midwestern pioneer, which seems to have been Wood’s primary conscious aim. At the same time, personal references inserted in the painting identify her as none other than the artist’s own mother, whom he idealized extravagantly as “the most beautiful lady in all the world.”11 In addition to the sansevieria, Hattie’s houseplants include begonias at the lower left of the picture, where Wood signed his name, identifying himself with the objects of her nurturing care. The windmill in the background also telegraphs his presence: “The Old Masters all had their trademarks,” he explained to Graham, “and mine will be the windmill”;12 the device appears behind him in an imposing self-portrait of 1932/41 (Figge Art Museum, Davenport, Iowa) and in its charcoal and pastel study (Introduction, opposite p. 1). Most tellingly, the cameo brooch Hattie wears at her throat testifies to her son’s heartfelt devotion: Wood had purchased it for her as a souvenir of his sojourn in Sorrento, Italy, in the winter of 1923–24.13

The cherished brooch reappears on the woman in American Gothic, as does Hattie’s simple black dress, worn beneath the rickrack-trimmed apron. Sansevieria and begonias are there too, though moved to the background, behind the woman’s shoulder, at the entrance to her house. Wood reprised in this younger female figure Hattie’s plain hairdo in Woman with Plants and her averted gaze. In both paintings, the women are rendered sexless, with flat chests; the “miniature breast–hieroglyph” Wanda Corn has identified in the dot-and-circle pattern of the apron in American Gothic suggests what Wood otherwise chose not to acknowledge.14 Curiously, the right breast of this figure seems to have dropped down to just above waist level. Wood also had some difficulty in “handling” his mother’s body in Woman with Plants, where her lap is rather clumsily delineated in visibly horizontal brushstrokes without convincing foreshortening. The ineptitude of this passage reminds us how maternal portraits are sometimes riddled with parapractic evidence of the artist’s emotional struggles, involving opposing desires for intimacy with and separation from the mother. Representing one’s mother can be a terribly “ticklish situation,” as critic Donald Kuspit observes, “fraught with the dangers of infantile response, with the threat of a regressive bonding with the mother” even as the artist strives to retain his autonomy as a mature adult.15 Wood idealized and clung to his mother, yet conflicts he was probably unaware of emerge in this portrait. It is worth noting, for example, how the indestructible sansevieria, typically understood to symbolize Hattie’s steadfast ...