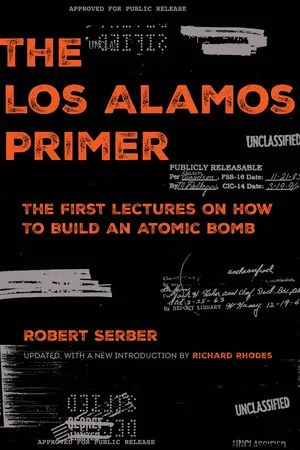

The Los Alamos Primer

The First Lectures on How to Build an Atomic Bomb, Updated with a New Introduction by Richard Rhodes

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Los Alamos Primer

The First Lectures on How to Build an Atomic Bomb, Updated with a New Introduction by Richard Rhodes

About this book

More than seventy years ago, American forces exploded the first atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, causing great physical and human destruction. The young scientists at Los Alamos who developed the bombs, which were nicknamed Little Boy and Fat Man, were introduced to the basic principles and goals of the project in March 1943, at a crash course in new weapons technology. The lecturer was physicist Robert Serber, J. Robert Oppenheimer's protégé, and the scientists learned that their job was to design and build the world's first atomic bombs. Notes on Serber's lectures were gathered into a mimeographed document titled The Los Alamos Primer, which was supplied to all incoming scientific staff. The Primer remained classified for decades after the war. Published for the first time in 1992, the Primer offers contemporary readers a better understanding of the origins of nuclear weapons. Serber's preface vividly conveys the mingled excitement, uncertainty, and intensity felt by the Manhattan Project scientists. This edition includes an updated introduction by Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Richard Rhodes. A seminal publication on a turning point in human history, The Los Alamos Primer reveals just how much was known and how terrifyingly much was unknown midway through the Manhattan Project. No other seminar anywhere has had greater historical consequences.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

The Los Alamos Primer

1. Object

2. Energy of Fission Process

Table of contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction by Richard Rhodes

- Preface by Robert Serber

- Illustrations

- The Los Alamos Primer

- Endnotes

- Appendix I: The Frisch-Peierls Memorandum

- Appendix II: Biographical Notes

- Notes

- Index