![]()

PART 1

Preparing for Self-Evolved Leadership

![]()

1

Break the Cycle of Mediocrity

“Sorry, Dave. I have to take this; it’s Steve.” Jen snatched her phone and stood up from the hefty desk we were sitting at and moved toward the corner window.

“Hey, Steve. What’s up?” she said as she plugged in her headset.

I thought back to when we started working together six months before. Jen had just been promoted to vice president of sales and marketing in a fast-growing tech company. Her rise through the ranks had been somewhat meteoric, and she was trying to come to terms with the responsibilities of her new role.

“OK, well, tell Eric I’ll call him this afternoon. Don’t worry, Steve. We’ll fix this.”

I knew by the look on her face that she meant “I’ll fix this.”

Jen moved back toward the table and set the phone down.

“Something up?” I asked. We both knew it was a leading question.

“That customer I was telling you about is just about to pull their business, and Steve needs me to put in a call to their purchasing guy to smooth things over.”

“Needs you to?” I asked. Jen shot me a look.

“Listen, Dave.” She moved toward me. “I know you’ve been helping me try to elevate my focus and not get in the weeds so much, but this is a full-blown crisis.”

I leaned back and put my hands up to signal that I wasn’t about to criticize the work she’d been doing.

“I completely understand that. Sounds as though you might have a genuine emergency on your hands,” I said. “Tell me, what has Steve done so far to try to keep the account?”

Jen sighed with a degree of resignation, then gritted her teeth. “I don’t know, Dave,” she said without seeming to move her jaw. “I didn’t ask him.”

“So, what’s your best outcome here?”

“Well, I guess I’ll call Eric, do my best to assuage his fears, and get him back on board.”

“And Steve? What does he take away from this?”

Jen shut her eyes, I think somewhat hoping that when she opened them, I’d be gone. “I get it, OK. I’ve just done that thing. What do you call it?”

“Built learned helplessness?”

“Yeah, that’s the one. Agghh, I hate when I do that. I’ve just gone back on the very first transition that we talked about, right? I’m getting pulled back into heroic leadership.”

“It’s OK!” I said, adopting a conciliatory tone. “Don’t beat yourself up. It happens all the time. Do you need to take a moment?”

“Yeah, let me call Steve back and see what he can do. Do you mind?”

“Not at all. I’ll go make myself a cup of coffee and meet you back here in fifteen.”

The Cycle of Mediocrity

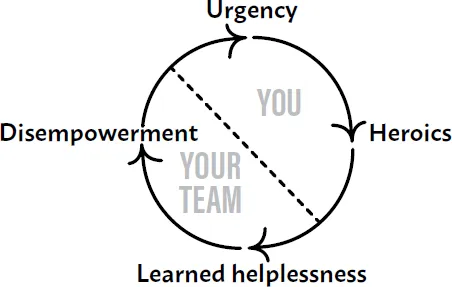

Jen, like so many other leaders before her, had fallen into a misguided way of thinking: that her value as a leader was found in her ability to fix things, to make the diving catches and save the day. Unfortunately, we’ve allowed a distorted image of what it means to lead to enter our organizations, and it’s causing a profound and dangerous knock-on effect on our teams. Let’s call it the Cycle of Mediocrity.

Urgency and Heroic Leadership

The growing complexity of our world and the speed at which things change and information is communicated have falsely led us to believe that it’s quicker and easier to act and act now rather than taking a moment to review the best course of action. So, when our largest customer is about to pull their business, we’ll get on the phone to our contact and save the day rather than getting our team involved. When our boss asks for the updated status report two days before it’s due, we pull an all-nighter to get it done instead of assessing the true urgency. When one of our team makes a simple mistake on this month’s financials, we fix it rather than sending it back with some feedback. We’ve allowed every input into our daily routine to become “urgent” and spend most of our time stuck fighting fires and lurching from crisis to crisis rather than affording ourselves the head-space to think about what’s important—the long-term direction of our team and the development of our people. We’re leading through acts of heroism.

This has been amplified by the fact that we have an ever-increasing list of role models for good leadership that are centered on the role of the hero. We’re bombarded with examples of heroes who save the day, from sports to the military to mythology.

These enigmatic figures pull victory from the jaws of defeat, they make the diving catches, they embark on a quest with a reluctant hope and emerge from their journey transformed. They may bring a team along with them, but without a standout quarterback throwing a Hail Mary or Captain America swooping in at the last minute, we all lose.

The problem is that none of these spheres are analogous to a growing organization. They come with their own rules and their own parameters for success. We don’t get to see what happens to the hero’s life once the final image of them in all their sweat, blood, and triumph fades away.

However, in the absence of a direct comparison, we’ve subconsciously translated our notion of the heroic leader from the worlds of sports, the military, and mythology to a corporate setting, and it isn’t pretty. We’ve lauded our workplace heroes and presented them with their own superpowers and, as a result, more and more leaders embody the following characteristics.

They Swing for the Fences

Heroic leaders say “yes” and then figure out how to deliver what they just agreed to do through brute force. For the heroic leader, getting the job done and satisfying the customer is almost more important than what the job is itself, and certainly more important than the impact it has on their team.

What happens then is that they say yes to a myriad of things and then have their team scramble like crazy underneath to make the whole thing come together. That’s not leadership. That’s throwing spaghetti at a wall, seeing what sticks, and then having your team clean up the mess.

They Confuse Busyness with Progress

Heroic leaders surround themselves in a dust cloud of activity, running from meeting to meeting, phone call to phone call, and watercooler conversation to networking event with nary a heartbeat to actually sit down and think through the decisions they’re making on any given day.

They hold the belief that as long as we continue to move in a direction, any direction, we’re making progress. In the wake of the leader’s busyness, however, they leave their team without clear direction, assuming that the team will magically understand their thoughts by sheer osmosis.

They Believe They Have the Answers

Anytime a team member approaches the heroic leader with a problem to be solved or a challenge that needs to be overcome, this type of leader instantly and without breath knows the right course of action to take (even if it isn’t the best decision) and quickly provides advice to unwitting team members like a Pez dispenser.

Heroic leaders believe that they are in the position they are in precisely because of this approach. It’s a feature, not a bug. As a result, their team becomes more and more reliant on the heroic leader to help them out of tricky situations.

They Save the Day

“I’ll deal with it.” The heroic leader’s favorite phrase. They view themselves not as the blocker and tackler for their team but as the quarterback throwing the Hail Mary. Why bother helping a team member devise a plan of action when it would take the heroic leader half the time to complete it and probably have it work out twice as successfully? Also, as this leader would be thinking, Let’s face it, I’ll probably have to jump in and fix it at some point anyway.

It’s not that heroic leaders are bad people. Most have good, if not great, intentions, but they find themselves in an almost addictive feedback loop. Each time we exhibit acts of heroism, we get a small dopamine hit that makes us feel valued, useful, and needed. We then start to (albeit subconsciously) seek out those opportunities. As a result, we begin to treat every interruption as an emergency, which in turn gives us an opportunity to get that hit of dopamine. Before you know it, we’ve found ourselves caught in an endless cycle of treating everything like a crisis that only we can solve.

Heroic leadership in your organization doesn’t have to happen in bold, sweeping ways to be harmful. You don’t have to embody all the characteristics listed above to be guilty of it. It can be as simple as saying something like, “Don’t worry, I’ve got it.” Or, “Leave that there, I’ll deal with it.” With every small drip of heroism, you’re further crippling the effectiveness of your team. In fact, you’re building learned helplessness within them.

Learned Helplessness

In 1974, Martin Seligman, then a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, and his colleagues sought to understand how humans react to unpleasant environments that appear beyond their control. In an experiment, they separated human subjects into three groups: One was subjected to an awful noise that they could control by pressing a button four times, the second experienced the same terrible din but the button they were given didn’t work, and the third heard no noise.

A little later, after the ear-ringing had subsided, the participants were all subjected to another obnoxious sound, but this time they had a lever rather than a button at their disposal to control it. Seligman and his associates found that those from the group with no control over their environment earlier that day, in general, did not try to use the lever to turn off the noise, while everyone else more or less managed to figure it out.

Seligman concluded that when faced with a situation over which you have no control, that feeling embeds itself cognitively and becomes an accepted truth. Even when things appear to have changed around you, your desire to change your circumstances decreases, and in turn, it can lead to a sense of depression. These subjects had developed learned helplessness.

I hate to break it to you, but most of your team has likely developed some form of learned helplessness from your acts of heroism. Not of the loud noise variety, but something much more subtle yet equally dangerous. In being an overwhelmed leader who is taking on too much and trying to save the day, you reinforce the belief that your team isn’t quite good enough, that it requires something special or magical from you to make it just so. That in itself puts a brake on your team’s desire to go above and beyond what’s necessary, and instead to sit back and wait for you to bail them out. It’s by no means malicious, nor is it likely to be what your team wants to happen. In fact, most of them probably don’t even realize they’re doing it when they are.

Disempowerment and Feeling Overwhelmed

In the long run, learned helplessness leads to disempowerment. Over time your team slowly cedes authority to you. They subconsciously elect not to make a tough call, so as to defer to your wisdom, to give you the final say.

You’ll notice that some on your team will willingly let this happen. For them, they feel more comfortable having someone else bear that load. For others, however, it’s more frustrating. They feel that the value they bring begins to erode. They may even resist initially, but as you continue to lead through heroics, eventually they too will start to gi...