![]()

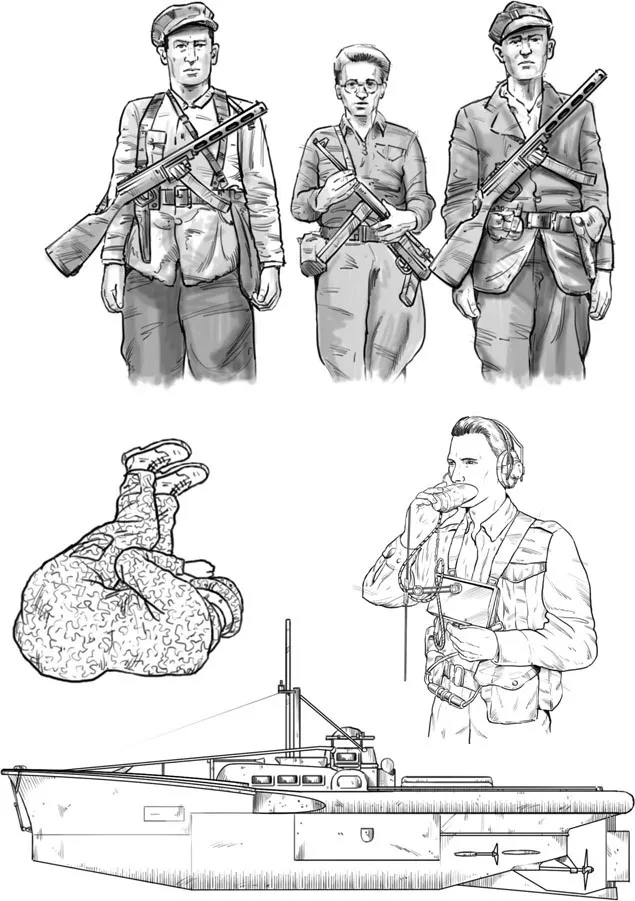

Insertion into occupied territory could be carried out via land, sea or air. This would often involve the use of special technology, such as an S-phone or Welfreighter boat.

1

Inserting agents and resistance fighters into enemy territory can be one of the most difficult and potentially hazardous parts of any clandestine operation.

Insertion

By the late summer of 1940 the newly formed Special Operations Executive (SOE) faced considerable difficulty in ‘setting Europe ablaze’ given that British forces had been ejected from the Continent following the evacuation from Dunkirk and subsequent fall of France. Thus virtually all efforts to undertake covert action in Nazi-occupied Europe required the insertion of agents from the United Kingdom and this meant crossing the Channel or, in the case of Norway, the North Sea. Thus SOE developed a whole series of techniques for transporting its members and equipment for the European resistance members it was supporting by sea and by air. The organization became skilled in the use of boats, submarines and aircraft, either landing or making drops by parachute.

The situation changed once Allied forces returned to mainland Europe via Italy in the autumn of 1943 and then into Normandy in June 1944. Although aircraft remained the mainstay for inserting agents and resupply, other, more traditional, means of moving through enemy lines and into their rear areas could be used. For the Soviets this was always the situation. In the campaign following the German invasion of June 1941, as the need to move through frontline areas was a constant requirement for Soviet Partisans, great consideration was given to the best means by which to cross through the front line.

By Air

For SOE, the key delivery system of both agents and supplies was the aircraft. There were two methods: the agent could be dropped off by a plane which had landed or make a parachute jump. Both had advantages and disadvantages. Parachuting meant less risk to the aircraft but did mean that agents and supplies might be scattered, damaged or both. Landing put the aircraft and pilot in greater danger, but allowed for greater precision and made injury to passengers and damage to equipment less likely. It also meant that verbal messages could be passed and agents extracted on the same trip.

At the end of Group A training prospective agents took the parachute course at Special Training School (STS) 51 at Manchester’s Ringway airfield. Agents’ first sessions were spent being dropped from special harnesses on to crash mats to simulate landings. This then progressed to jumping from a 23m (75ft) tower and then to a static balloon 213m (700ft) up. Finally, there came three daylight drops from an aircraft and two at night. The students needed to master basic parachute landing technique and learn the necessity of keeping both legs together to lessen the chance of breaking something. This had to become instinctive as there would be no time to think when the time came for real.

Aircraft Employed

The aircraft that operated in support of SOE were usually obsolete or obsolescent bombers. The RAF’s Bomber Command was loath to equip the squadrons that supported SOE with modern aircraft. Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal, Chief of the Air Staff, told SOE that ‘your work is a gamble which may give us valuable dividend or may produce nothing. It is anybody’s guess. My bombing offensive is not a gamble, its dividend is certain; it is a gilt edged investment. I cannot divert aircraft from a certainty to a gamble which may be a gold-mine or may be completely worthless.’ As a result, the number of available aircraft was small, certainly in comparison to the vast bomber fleets sent against Germany and other targets in occupied Europe.

Only five British-based aircraft were to work with the Resistance until August 1941. By the end of the following year it was still under 30 and the number of aircraft available to SOE on a full-time basis never passed 60. Two squadrons, No. 138 and No. 161, undertook the missions from a carefully disguised aerodrome at Templeford near Cambridge.

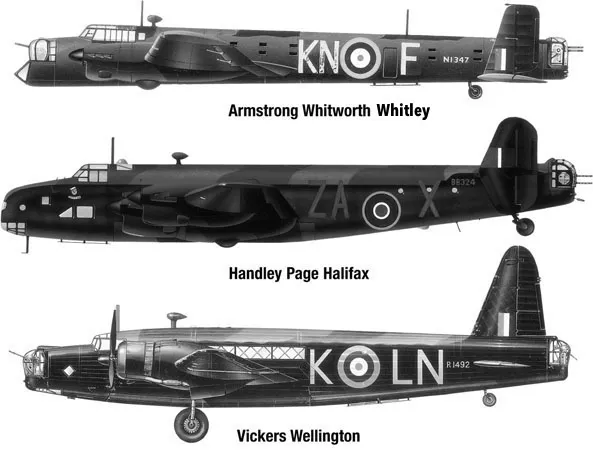

Allied Aircraft Types

RAF support for SOE was largely in the form of its ageing heavy bombers. Initially, the Whitley and later aircraft such as the Wellington and Halifax dropped agents and supplies across Europe.

Occasionally, the base at Tangemere in Kent was made available and extra support could occasionally be loaned from Transport or Bomber Command. The USAAF added two more squadrons flying Liberators and Dakotas in January 1944.

Equipment Profile:

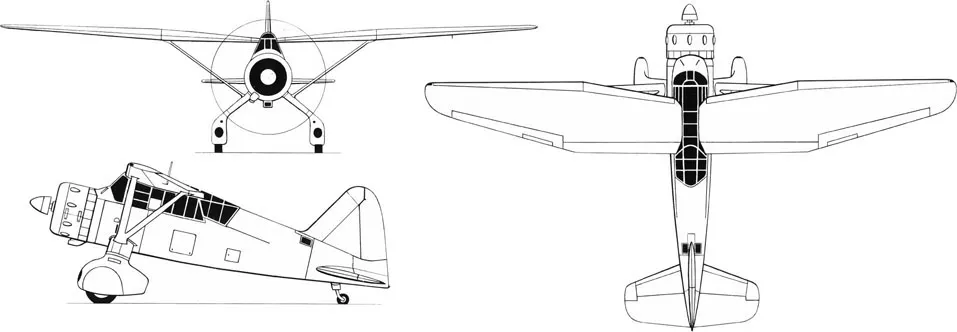

The Westland Lysander Mark III

The Westland Lysander was designed as an army cooperation and light support aircraft. It entered service in 1938 and saw action in France in 1940, which exposed its limitations as a frontline combat aircraft. However, the ‘Lizzie’, as it was known, really came into its own as a support aircraft for SOE and Britain’s intelligence services. The aircraft’s sturdiness, manoeuvrability and extraordinary ability to take off and land within a small area made it ideal for clandestine work. As SOE’s official historian, M.R.D. Foot wrote, ‘as Voltaire said of God, that had it not existed it would have had to have been invented’.

Crew: 1

Passengers: 1–2 (3 at most).

Powerplant: One 649kW (870hp) Bristol Mercury XX 9-cylinder air-cooled radial engine.

Performance: Maximum speed 341km/h (212mph) at 1525m (5000ft); service ceiling 6555m (21,500ft).

Fuel Capacity: 482 litres (106 Imperial gallons) in a fuselage tank. The Lysander Mk IIISCW could carry an external long-range tank of 150 Imperial gallons (682 litres) could also be carried to extend the range.

Range: 966km (600 miles) on internal fuel; 1448km (900 miles) with external tank.

Weight: Empty 1980kg (4365lbs) with a maximum take-off weight of 2865kg (6318lbs).

Wing Span: 15.24m (50ft).

Length: 9.3m (30ft 6in).

So, when planning air drops, the relative working radii of the aircraft had to be taken into account. The Armstrong Whitworth Whitley could operate out to about 1368km (850 miles), the Vickers Wellington had a slightly shorter range, and the Handley-Page Halifax, a few of which were added to Nos 138 and 161 Squadrons’ roster from August 1941, had a similar range too. The Liberators used by the USAAF could reach a couple of hundred miles further. For landing agents, the preferred aircraft was the Westland Lysander, an aircraft designed for reconnaissance and artillery spotting. It was perfect for delivering agents, being sturdy, manoeuvrable and having superb short take-off and landing capabilities, although being a much smaller single-engined aircraft, its operational radius was a much shorter 724km (450 miles).

SOE also used the Lockheed Hudson, a much larger twin-engined light bomber in this role. It could carry a Rebecca airborne receiver for the Eureka homing beacon and comfortably carry 12 men or a ton of stores. However, it required a kilometre or so of flat meadow in which to land and take off. So the range of these aircraft meant that large areas of Eastern Europe, such as eastern Poland, Finland and the USSR, which was particularly wary of aircraft operating for foreign secret services anyway, were outside SOE’s supporting aircrafts’ range.

The following section is adapted from ‘The SOE Syllabus: Selection of Dropping Points and Landing Sites, July 1943’, in How to be a Spy: The SOE Training Manual.

Selection of the Drop Zone

The reception committee is responsible for selecting the drop zone. This must meet certain basic principles. Dropping operations take place on moonlit nights by aircraft flying between 152 and 182m (500 and 600ft) at 160–193km/h (100–120 mph). Therefore, an open area of ground not less than 548m (600 yards) square is required. This should be increased to at least 731m (800 yards), if several containers or men are being dropped. This area will be sufficient, whatever the wind direction. Drops should not take place if the wind speed is above 32km/h (20mph). Agricultural ground and swamps should be avoided. Ploughed fields are a physical hazard to landing parachutists and damage to the crops might leave evidence of the landing. The area should be free of telegraph or high-tension wires. While cover in the immediate vicinity is an advantage, high trees are also a hazard to be avoided.

The selection of the site must always take into consideration three major concerns:

1) The safety of the dropping aircraft.

2) The site’s easy recognizability at night.

3) The planning and make-up of the reception committee.

Aircraft Safety

To ensure the safety of the aircraft three main points should be observed:

1) The area should be away from heavily defended areas, to avoid flak concentrations. Enemy aerodromes are particularly dangerous and should be avoided at all costs.

2) The selected area should be as level as possible. Mountainous and high country should be avoided if possible, but a high plateau might be usable if it meets the correct dimensions. Valleys should also be avoided unless particularly wide.

3) The dropping aircraft must be clear of enemy territory by daybreak and, therefore, travelling times and distances (usually from the UK) must be taken into consideration.

Recognizability of Site

To ensure the site’s recognizability at night the following issues should be taken into consideration. A pilot flying at 1828m (6000 feet) on a moonlit night should easily be able to spot the following points to aid navigation:

1) The coastline, if possible with breaking surf; and river mouths over 47m (50 yards) wide.

2) Rivers and canals. Both provide moon reflection, which is helpful. Wooded banks may reduce this. A river needs to be at least 27m (30 yards) wide. This is less important with regard to canals as their unnatural straightness will aid identification. There is a danger of misidentification if the area is crisscrossed with numerous rivers.

3) Large lakes, at least half a mile wide. Care should be taken if there is more than one in the area.

4) Forests and wood blocks. Need to be at least 0.8km (0.5 miles) wide and of a regular shape. Consult a recent map in case of recent felling, which might have altered the profile.

5) Straight roads, at least 1.6km (1 mile) in length, are good navigation guides, particularly when wet. Narrow or winding lanes are of no use.

6) Railway lines. Only useful in winter when snow is on the ground as a main line cuts a distinctive black ribbon across the landscape.

7) Towns and built-up areas. In conditions of black-out, towns are unlikely to be of much use unless over the size of 20,000 inhabitants. One needs to consider the possibility of anti-aircraft defences.

It is clear, therefore, that areas of water provide the best points for quick recognition...