![]()

CHAPTER ONE

A New Perspective on Educational Objectives

This handbook is a guide to the design and assessment of educational objectives. It is a practical application of The New Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Marzano & Kendall, 2007). While the New Taxonomy has a number of potential uses, here we focus on designing and assessing educational objectives. As indicated by its title, The New Taxonomy is designed as a replacement for Bloom et al.’s taxonomy, published in 1956 (Bloom, Englehart, Furst, Hill, & Krathwohl, 1956) Although that work was powerful and enduring, it had some flaws and inconsistencies that can now be reconciled, given the sixty-plus years of research and theory since its publication (for a detailed discussion, see Marzano & Kendall, 2007).

Bloom’s taxonomy made a major contribution to the science of designing educational objectives. Indeed, prior to its publication, there was not much agreement as to the nature of objectives. Bloom adopted Ralph Tyler’s (Airasian, 1994) notion that an educational objective should contain a clear reference to a specific type of knowledge as well as the behaviors that would signal understanding or skill related to that knowledge.

Like Bloom’s taxonomy and others based on it (e.g., Anderson et al., 2001), the New Taxonomy has a specific syntax for educational objectives. We use the following stem for all objectives: The student (or students) will be able to … plus a verb phrase and an object. The verb phrase states the mental process that is to be employed while completing the objective, and the object is the knowledge that is the focus of the objective.

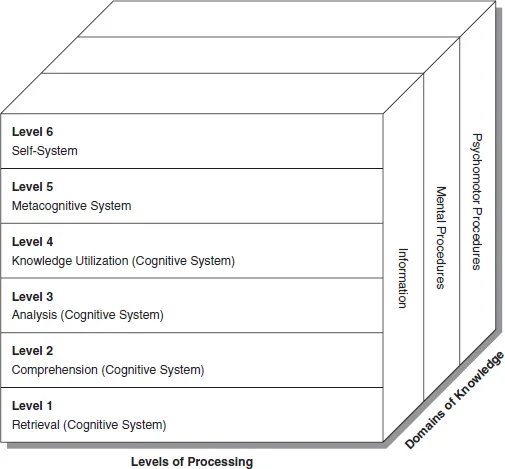

The New Taxonomy can be represented as depicted in Figure 1.1. The rows on the left-hand side of Figure 1.1 represent three systems of thought and in the case of the cognitive system, four subcomponents of that system. The columns on the right-hand side of Figure 1.1 depict three different types or domains of knowledge: information, mental procedures, and psychomotor procedures. In effect, the New Taxonomy is two-dimensional. One dimension addresses three domains of knowledge; the other addresses levels of mental processing.

Figure 1.1 The New Taxonomy

Source: Marzano & Kendall (2007)

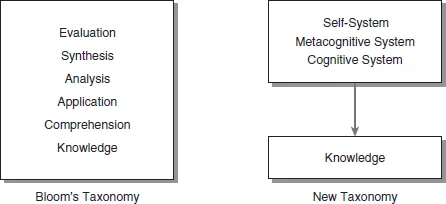

One of the defining differences between Bloom’s taxonomy and the New Taxonomy is that the New Taxonomy separates various types of knowledge from the mental processes that operate on them. This is depicted in Figure 1.2.

As shown in Figure 1.2, Bloom included knowledge as a component of his taxonomy. About this, Bloom and his colleagues (1956) noted,

By knowledge, we mean that the student can give evidence that he remembers either by recalling or by recognizing some idea or phenomenon with which he has had experience in the educational process. For our taxonomy purposes, we are defining knowledge as little more than the remembering of the idea or phenomenon in a form very close to that in which it was originally encountered. (pp. 28–29)

Figure 1.2 Knowledge as Addressed in the Two Taxonomies

Source: Marzano & Kendall (2007)

On the other hand, Bloom identified specific types of knowledge within the knowledge category. These included

Terminology

Specific facts

Conventions

Trends or sequences

Classifications and categories

Criteria

Methodology

Principles and generalizations

Theories and structures

Thus within his knowledge category, Bloom included various forms of knowledge as well as the ability to recall and recognize that knowledge. This mixing of types of knowledge with the various mental operations that act on knowledge is one of the major weaknesses of Bloom’s Taxonomy since it confuses the object of an action with the action itself. The New Taxonomy avoids this confusion by postulating three domains of knowledge that are operated on by the three systems of thought and their component elements. It is the systems of thought that have the hierarchical structure that constitutes the New Taxonomy.

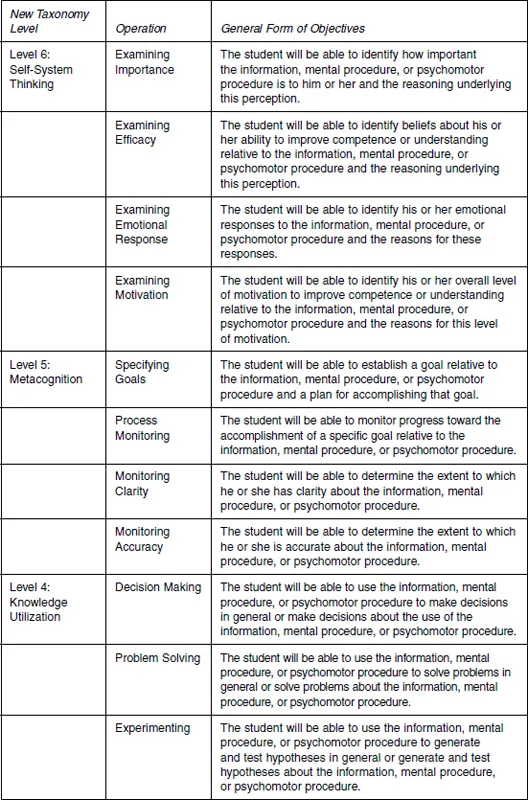

We consider the specifics of the New Taxonomy in Chapter 2. Here we briefly introduce the framework to demonstrate the nature and format of the educational objectives that can be designed and assessed using it. To illustrate, consider Figure 1.3.

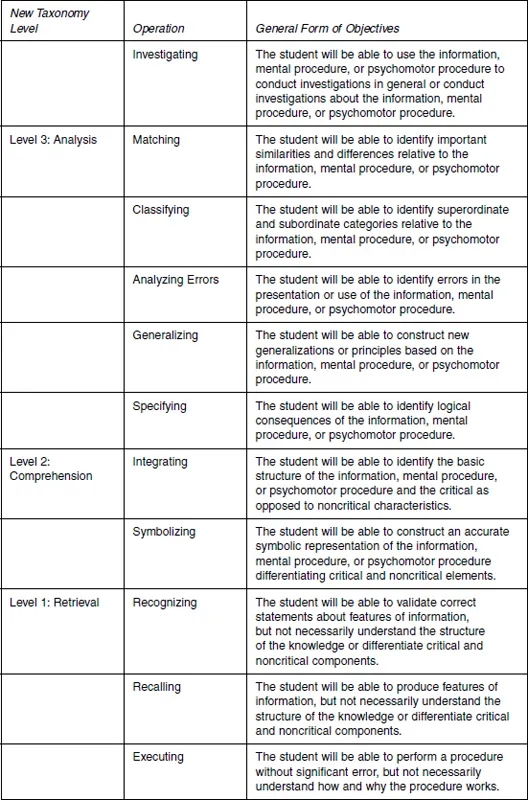

Figure 1.3 General Form of Educational Objectives for Each Level of the New Taxonomy

Source: Marzano & Kendall (2007)

The rows of Figure 1.3 represent the various levels of the New Taxonomy. The third column of Figure 1.3 portrays a generic form of the objectives that might be generated for each level of the New Taxonomy. Subsequent chapters provide specific examples of educational objectives, along with tasks that might be used to assess those objectives, for each level of the New Taxonomy across the three domains of knowledge. To obtain a sense of the objectives that might be generated and assessed using the New Taxonomy it is useful to start with retrieval objectives—the bottom of the New Taxonomy.

Retrieval objectives involve the recognition, recall, and execution of basic information and procedures. These are very common in education and were addressed in Bloom’s “knowledge” level.

Comprehension objectives involve identifying and symbolizing the critical features of knowledge. These too are quite common among educational objectives. Comprehension in the New Taxonomy is similar to comprehension in Bloom’s taxonomy; however, Bloom’s taxonomy does not contain a process akin to symbolizing knowledge.

Analysis objectives involve reasoned extensions of knowledge. They are sometimes referred to as higher order in that they require students to make inferences that go beyond what was directly taught. The New Taxonomy involves five types of analysis processes: matching, classifying, analyzing errors, generating, and specifying. Matching in the New Taxonomy is similar to what Bloom refers to as analysis of relationships within Level 4.0 (analysis) of his taxonomy. Classifying in the New Taxonomy is similar to what Bloom refers to as identifying a set of abstract relations within Level 5.0 (synthesis) of his taxonomy. Analyzing errors in the New Taxonomy is similar to what is referred to as judging internal evidence within Level 6.0 (evaluation) of Bloom’s taxonomy. It is also similar to analysis of organizing principles within Level 4.0 (analysis) of Bloom’s taxonomy. Generalizing and specifying in the New Taxonomy are embedded in many components from Levels 4, 5, and 6 of Bloom’s taxonomy.

Knowledge utilization objectives are employed when knowledge is used to accomplish a specific task. Such objectives are frequently a part of what some educators refer to as authentic tasks. The New Taxonomy includes four knowledge utilization processes: decision making, problem solving, experimenting, and investigating. The overall category of knowledge utilization is most closely related to synthesis (Level 5.0) in Bloom’s taxonomy.

Metacognitive objectives address setting and monitoring goals. Although the importance of these behaviors is recognized by educators, it is rare that spec...