![]()

![]()

1

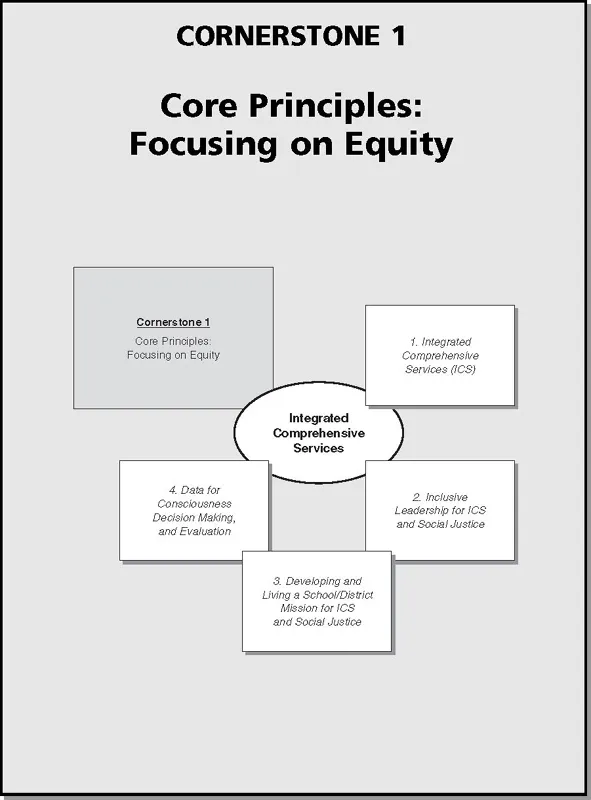

Integrated Comprehensive Services (ICS)

Throughout the past decade, the research and literature on inclusive education has increased significantly (Peterson & Hittie, 2003). This literature predominantly positions the unit of analysis at the classroom level. For example, many researchers have focused their attention on the social and academic outcomes of integrated education (Peterson & Hittie, 2003; Rea, McLaughlin, & Walther-Thomas, 2002), on collaborative teaching arrangements (Thousand, Villa, & Nevin, 2002), on the role of paraprofessionals (Doyle, 2002), on including students with disabilities in district and state assessments (Thurlow, Elliot, & Ysseldyke, 1998), or on ways to integrate curriculum (Rainforth & Kugelmass, 2003). Others have offered a conceptual and ideological analysis of the literature in support of or against inclusive education (Brantlinger, 1997). However, literature that focuses specifically on the role of school leaders with students who typically struggle (Riehl, 2000), or organizational, structural, and cultural conditions necessary for inclusion, is significantly less comprehensive. Even book-length works whose titles suggest a focus on whole-school restructuring to serve students (e.g., Sailor, 2002) do not address the school- or district-level organizational and structural implementation intricacies of serving students in heterogeneous classrooms. Exceptions to this include work by Burrello, Lashley, and Beatty (2000); Capper et al. (2000); and McLeskey and Waldron (2000). However, this literature focuses primarily on students with disability labels and does not take into account how providing services for such students is similar to and different from addressing the needs of other students who may struggle in school, such as students for whom English is not their primary language, students considered “at-risk,” students considered gifted, or students with lower reading levels.

The recent comprehensive school reform (CSR) models by design come closest to taking such a whole-school approach to raising the academic achievement of all students (Borman, Hewes, Overman, & Brown, 2003); however, even CSR does not specifically address the needs of students with disabilities. Though this literature explains how lower achieving students can experience academic success, the research does not articulate how students with disability labels have experienced similar success, nor do we know from this literature to what extent students with disabilities are included in heterogeneous class environments in these models of reform. In addition, none of the CSR models make disability the focus.

The purpose of this book is to address this gap in the literature by taking each school as the unit of analysis, and focusing on specific school-level organizational conditions necessary for schools to deliver what we call Integrated Comprehensive Services (ICS) in heterogeneous environments for all learners. Integrated environments are the settings that all students, regardless of need or legislative eligibility, access throughout their day in school and nonschool settings. That is, in these settings (e.g., classroom, playground, library, field trips), students with a variety of needs and gifts learn together in both small and large groups. Comprehensive services refer to the array of services and supports, centered in a differentiated curriculum and instruction, that all students receive to ensure academic and behavioral success. By all learners, we mean especially to include those learners who have been designated to receive services such as those labeled with a disability or labeled at-risk, gifted, low readers, or English language learners (ELL).

We will first address why changes in service delivery are vitally necessary, pointing to the current status of special education, including the growing incidence of students labeled with disabilities, the historically poor school and post-school outcomes of special education efforts, and the enormous outlay of financial and other resources into activities with such poor outcomes. We follow this with a description of the differences between providing programs for students and bringing services to students via ICS, and the principles that should guide the delivery of educational services to all students. What we mean by service delivery are the ways in which students are provided educational services, including curriculum, instruction, assessments, and any additional supportive services that are necessary for the student to be successful in heterogeneous learning environments.

OUTCOMES OF SEGREGATED PROGRAMS

The number of students labeled with a disability has increased 151% since 1989 (Ysseldyke, 2001). In addition, students of color are significantly overidentified for and overrepresented in special education (Donovan & Cross, 2002; Hosp & Reschly, 2002; Losen & Orfield, 2002; Quality Counts, 2004; Zhang & Katsiyannis, 2002). Unfortunately, these students often spend the largest part of their day away from their classroom receiving special instruction, resulting in a disconnected and fragmented school day (Capper et al., 2000). Moreover, these special programs have failed to result in high student achievement as measured by post-school outcomes or standardized scores. For example, in the United States, despite extensive efforts at providing special education for more than 25 years since the implementation of federal disability law, 22% of students with disability labels fail to complete high school, compared to 9% of students without labels (National Organization on Disability, 2000). For a more specific example, in one Midwestern state, 13.8% of students with disability labels drop out, compared to 8.2% without labels (Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, 2005). Of these students, 50% of those who are labeled with emotional disturbance drop out. In addition, 21.7% of students with learning disabilities, 25% of students labeled for speech/language issues, 24.9% of students with mental retardation, and 9.5% of students with autism all fail to complete high school. Further, 11.68% of students with disability labels are suspended, compared to 5.15% of students without labels (Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, 2005).

Equally alarming are the poor long-term outcomes of these special education efforts. For example, according to a study by Blackorby and Wagner (1996), “nearly 1 in 5 youth with disabilities out of school 3 to 5 years still was not employed and was not looking for work,” while 69% of students from the general population over that same period of time were employed (pp. 402–403). After providing special education to students for at least 18 years in public schools and in many cases for 21 years as mandated by the special education law, these school and postschool outcomes are indeed dismal.

Not only are the special education outcomes dismal, the amount of money educators have put forth to support these failing efforts is staggering. Special education in special programs costs 130% more than general education. That is, if a school district spends $5,000 per student, then each student labeled for special programs costs districts $11,500 (Odden & Picus, 2000). In the 1999–2000 school year, “the 50 states and the District of Columbia spent approximately $50 billion on special education services, amounting to $8,080 per special education student” (Chambers, Parrish, & Harr, 2002, p. v). In comparison, in 1998, total instructional expenditures for students at the elementary/middle school level who are served in the general education classroom was $3,920 (Chambers, Parrish, Lieberman, & Wolman, 1998).

Relatedly, the more students are served in restrictive, segregated placements, the higher the cost of the education. For example, Capper et al. (2000) note that

That is, the data clearly show that the more students are segregated from their peers for instruction, the more costly is that instruction. The reason for this is that “a separate program means that students often require separate space, separate materials and infrastructure, a separate teacher, and an administrator not only to manage the program but also to spend time and money on organizing the program” (Capper et al., 2000, p. 7).

Though separate alternative and charter schools are quite costly, as of January 2004, a total of 1,996 charter schools were operating across the United States (see http://www.uscharterschools.org). Just as separate programs within public schools track disproportionate numbers of students of color and lower income students into these programs (see Capper & Young, in press), charter schools suffer the same problem. For example, these charter schools

Similarly, during the 2000–2001 school year, 10,900 public alternative schools and programs for so-called “at-risk” students were in operation, and 59% of these programs were housed in a separate facility (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2004, p. 33). Districts with high percentages of students of color and low-income students tended to have higher enrollments in alternative schools (NCES, 2004, p. 33).

Moreover, educators spend an inordinate amount of time and resources deciding exactly for which program a student may qualify. In the Verona (Wisconsin) school district in 1999, “it cost more than $2,000 to evaluate one student to determine eligibility for special education. [In this case,] a district of 4,500 students averages 225 (5%) evaluations per year for a total of $443,713 spent on evaluations alone” (Capper et al., 2000, p. 7).

According to the U.S. Department of Education (2000), “Slightly under half [of students with disability labels] between the ages of six and seventeen are served in general education settings with their [typical] peers for more than 89% of their school day … and the number of students served in general education classrooms is increasing each year” (cited in Causton-Theoharis, 2003, p. 7), due in part to the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA) 1997, which created “a legal presumption in favor of regular class placement” (Huefner, 2000, p. 242, cited in Causton-Theoharis, 2003, pp. 6–7). Research suggests that educating students in these general education environments results in higher academic achievement and more positive social outcomes for students with and without disability labels (McLeskey & Waldron, 2000; see Peterson & Hittie, 2003, pp. 37–39 for additional studies; Rea, McLaughlin, & Walther-Thomas, 2002), not to mention that it is the most cost-effective way to educate students.

In sum, more students are being labeled with disabilities, due in large part to the failure of the education system. Though more of these students are being educated in heterogeneous educational environments than in previous years, increasingly students who are labeled “at-risk” are being placed in segregated, alternative classrooms and schools. Many students are not served in their neighborhood schools (or the school they would attend if they did not have the disability or other program label) and spend large parts of their days out of the general education classroom. Not only are these practices failing to meet the needs of these students, resulting in significantly high percentages of students dropping out of school or not being employed after secondary education, but these practices also exact an exorbitant financial toll on schools and districts.

To overcome these costly, dismal outcomes of segregated programs, school leaders (i.e., principals, school-based steering committees, site councils, etc.) must focus their efforts on preventing student struggle and must change how students who struggle are educated. In so doing, fewer students will be inappropriately labeled with disability or educational at-risk labels, and more students will be educated in heterogeneous learning environments, resulting in higher student achievement and more promising post-school outcomes.

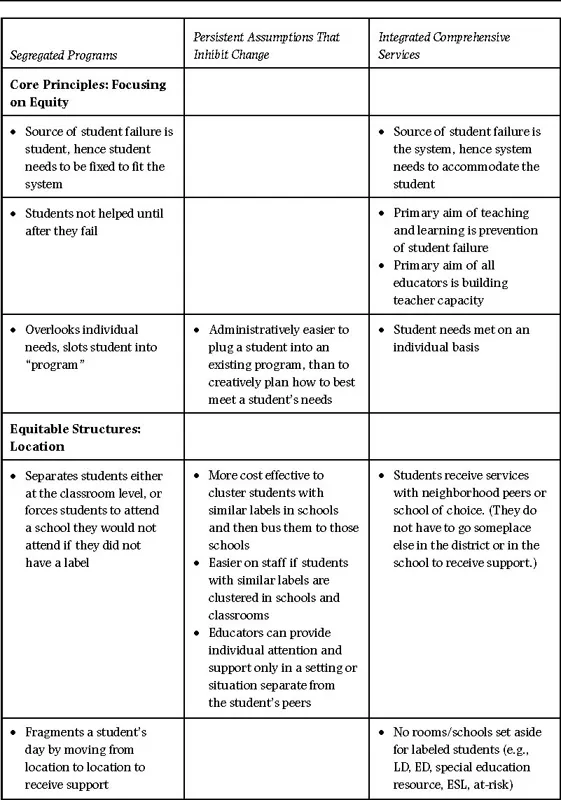

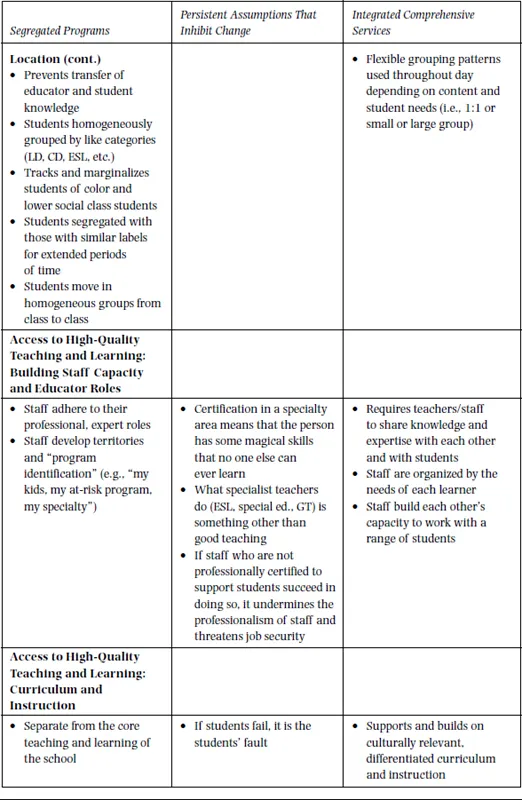

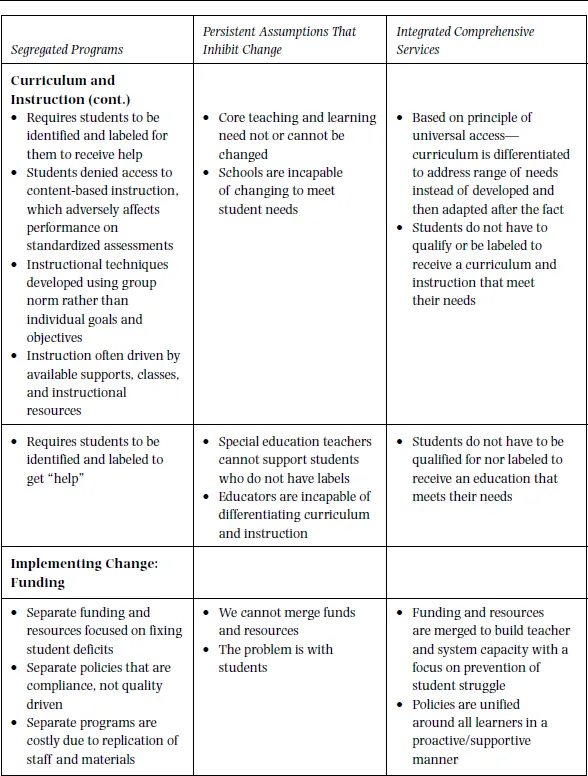

Placing students in special programs is quite the opposite of providing services to students (i.e., ICS). The two approaches differ in the following ways: core principles, location, educators/staff, curriculum and instruction, and funding (see Table 1.1). In our work with educators across the country and with our students, we also hear persistent assumptions about the factors that inhibit change toward ICS. As we describe the differences between special programs and ICS, we will also identify these assumptions and describe the evidence-based practices that refute them.

Table 1.1 Differences Between Segregated Programs and Integrated Comprehensive Services (ICS)

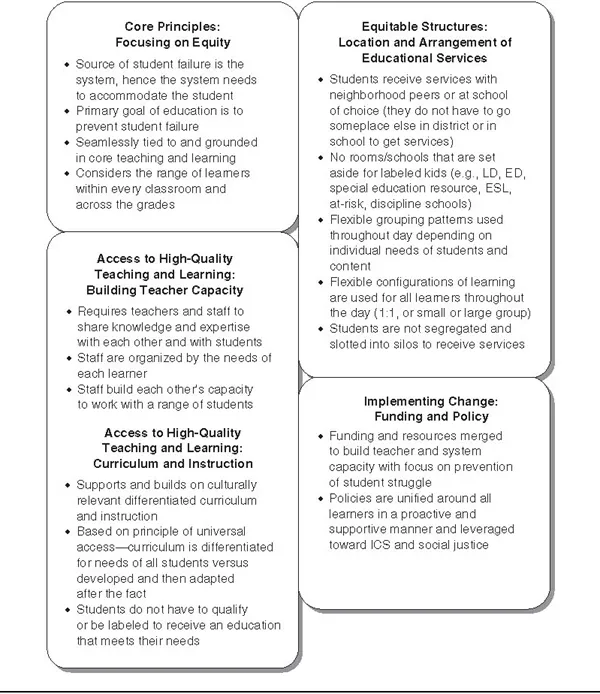

CORE PRINCIPLES: FOCUSING ON EQUITY

One core principle of segregated special programs is that students do not receive help for their learning needs until after they fail in some way. This practice is akin to parking an ambulance at the bottom of a cliff to assist people who fall off the cliff. Special programs are the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff. Students are placed in them after they fail, academically, socially, or behaviorally.

In contrast, with ICS, the primary aim of teaching and learning in the school is prevention of student failure. Referring again to the analogy above, ICS works at the top of the cliff, setting up supports that not only prevent students from falling off the cliff, but also keep them from nearing the cliff in the first place. It is astounding to us how so few educational practices are considered preventative. One activity we conduct in our graduate leadership preparation classes is to have students map out their response to this question: “What happens in your school or classroom when a student struggles, academically, socially, or behaviorally? What are all the practices in place to address this?” Invariably, students easily list a wide range of “ambulances” numbering up to a couple of dozen even in small schools and districts. The list includes items such as homework club, learning centers, peer tutors, adult volunteers, Title 1 reading, Reading Recovery, school-within-a-school programs, small-group tutoring, Saturday morning remedial club, summer school, calling parents, in and out of school suspension, and the list goes on. Then, we ask our students to list all the actions their school or districts take to prevent student academic or behavioral failure or struggle in the first place. This request is usually followed by several minutes of quiet, as such efforts do not readily come to students’ minds. Finally, students will list a few practices such as focused, intensive reading instruction in the early grades or differentiating instruction.

Figure 1.1 Cornerstone Details of ICS

According to Deschenes, Cuban, and Tyack (2001), historically, public schools have dealt with student failure in similar ways—blaming the student, or factors beyond the school (e.g., families, communities, and so forth; see Valencia, 1997, on deficit theory). With ICS, the onus of student failure is on the school, and any student failure is viewed as something that is askew in the educational system. The way educators frame student failure (i.e., whether student failure is seen as a student or a systems issue) is the pivot point of all the remaining assumptions and practices in schools.

As such, the primary aim of ICS is the prevention of student failure, and student failure is prevented by building teacher capacity to be able to teach to a range of diverse student strengths and needs, a second core principle. Every single decision about service delivery must be premised on the extent to which that decision will increase the capacity of all teachers to teach to a range of students’ diverse learning needs. Segregated special programs, by definition, diminish teacher capacity. When the same student or group of students is routinely removed from the classroom to receive instruction elsewhere, the classroom teacher is released from responsibility for learning how to teach not only those students, but all future students with similar needs over the rest of that teacher’s career. At the same time, students with and without special needs are denied the opportunity to learn and work with each other, while the students who leave the room are denied a sense of belonging in the classroom.

A third core principle of separate programs is that these efforts do not address individual student needs. Instead, students are made to fit into yet another program. Even the language used often reflects this idea. That is, we use language such as, “we need to program for this student.” “We held a meeting to program for this student.” “We can place the student in the CD program.” “That school houses the ED program.” The forcing of students to fit into a program is a supreme irony of programs that are created under the assumption that students do not fit into general education, hence they need something unique and individual, but are then required to fit into yet another program. A persistent assumption with this principle is that it is administratively easier to plug a student into an existing program than to creatively plan how to best meet a student’s academic or behavioral needs (both of which are mandated in special education legislation).

When educators in a school have made significant progress toward restructuring based on ICS principles, one practical way to avoid placing students in prepackaged programs and to meet individual student needs can take place in IEP meetings. In these meetings, practitioners who are working toward dismantling segregated programs and moving to ICS have found it helpful to assume that no separate programs exist in their schools. They ask themselves the question, if no such program existed, how would we best meet this student’s needs? And how can that decision ultimately build teacher capacity?

In addition to the core principals that distinguish ICS from segregated programs, these two different models of service delivery also differ from each oth...