![]()

1

An Overview of the Vocabulary Pyramid

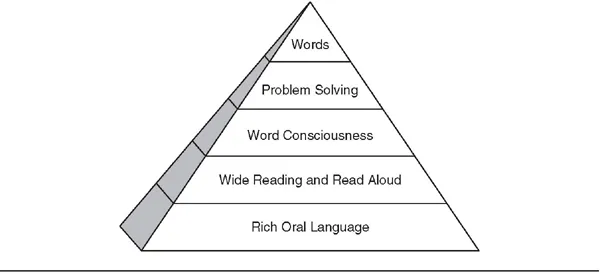

THE VOCABULARY PYRAMID

Figure 1.1

When you think about eating, you may think about hamburgers, good wine, and chocolate cake. We know that isn’t a balanced diet, however, and most of us are at least aware of what a good diet should look like. It’s the one we want our children to eat—with six to eight glasses of water, full of fresh fruit and vegetables, a sampling of complex carbohydrates, and minimal fatty proteins. What we want to convey in this book is the analogy that word learning is (1) essential for a healthy academic life, (2) has several components that can be compared to the food pyramid (before it was recently tipped on its side) in terms of frequency and daily diet, and (3) has a scope that goes beyond learning simple definitions. Learning definitions for words is merely the tip of the pyramid!

The purpose of a strong vocabulary program is to provide students with a solid foundation for participating fully in their school experiences. Providing students with a healthy breakfast enables them to concentrate more fully on their learning. Providing students with a healthy word diet enables them to comprehend and communicate more fully.

RICH ORAL LANGUAGE

Let’s start with the base of the pyramid: rich oral language. This is the foundation of our program. Compare it to drinking six to eight glasses of water every day. Although water isn’t generally considered part of the food pyramid, it is essential to healthy living. Water keeps your skin hydrated, is necessary for general well-being and health, and keeps all your systems flowing smoothly. Rich oral language lubricates the system of word learning. It is an essential element of communication.

What does rich oral language look like and why is it important?

Scenario

A three-year-old picks up a rusty nail on the sidewalk.

| Adult #1: |

“What do you have? Let me have that!” (end of conversation) |

| Adult #2: |

“What do you have? Oh, a rusty nail! That’s dangerous, so please be careful. Can I please have that? See the sharp point at the end? It can puncture your skin and, because it’s rusty, it may have nasty germs on it that can make you sick. It’s not a good idea to pick up rusty sharp objects like that.” |

Can you see how the second adult extends the knowledge of the child through conversation in this scenario? And, in the course of the conversation, the adult has introduced words—such as rusty, dangerous, sharp, puncture, nasty, germs, and objects—within a meaningful context.

Words are primary in how we, as humans, communicate. We have both receptive and expressive vocabularies. The more extensive our expressive vocabulary, the more precisely we can convey our message to other people through written and spoken language. The more extensive our receptive vocabulary, the more likely we will be to encounter known words when we read. The child associated with the understand others and to adult in the second scenario above is more likely to understand and use the words she hears in context. Thus, when that child attempts to read and comes across the word rusty in a book, she can map the sounds she hears with a known word in memory. If another child hasn’t had experience with the word rusty, he is in the more difficult position of figuring out a meaning for the word as well as decoding it. It is only when you know a word that you are likely to use it in writing and speech.

Whether we cut short or extend conversations presents differential patterns in word learning. Exposing children to the type of words found in rich oral discussions can make a difference in their academic success. Children exposed to varied vocabulary and rich discussions in homes or preschools, the type of discussion that stimulates children’s thinking, have higher literacy scores in kindergarten, fourth, and seventh grade (Dickinson & Tabors, 2001). In addition, this type of environment can compensate for differences in the match between language used in homes and that used in schools (Dickinson & Tabors, 2001).

Perhaps you can see now why we put rich oral language at the base of the pyramid. Teachers and parents who engage children in discussions about the world are developing not only their understanding of the way the world works, but also an understanding of the words used to describe and explain that world.

WIDE READING AND READ ALOUD

The second foundational level of our program is active and explicit exposure to written language found in novels, picture books, poems, and informational texts. Reading aloud to students of all ages exposes them to the richness of language not found in everyday oral communication. This is the breads and cereals level of vocabulary learning, the base of the old food pyramid. We suggest at least six good-sized helpings of read aloud and independent reading throughout each day.

Not all words occur equally often in English. Some words, like have and go, are incredibly common and are a part of the 100 most common words that make up about 50 percent of the material we read. Other words, such as exoskeleton, occur fewer than once per one million words of text. Then there are the words in between, not incredibly common but seen regularly in text and used somewhat often in speech, such as universe and risk. Most of us use relatively few words when we talk. The language in children’s books, on the other hand, is often rich and powerful (Hayes & Ahren, 1988).

The words intricate, baffling, chalice, acquired, incalculable, inscriptions, decipher, appealed, substantial, grail, unprecedented, exceeds, and intrinsic all appear on the first page of the children’s book, Greenwitch, a 131-page novel by Susan Cooper. How often do you use such words at the dinner table? Exposure to words in stories and discussions around the words help students expand their vocabularies (Elley, 1989; Penno, Wilkinson, & Moore, 2002; Robbins & Ehri, 1994). Stopping to explain or discuss the words, as well as reading the stories several times, helps consolidate this word knowledge (Biemiller, 2004; Elley, 1989; Penno et al., 2002; Robbins & Ehri, 1994).

Independent reading is also important. Students learn both unknown words and partially known words when they read texts independently, with similar gains for each (Schwanenflugel, Stahl, & McFalls, 1997). A meta-analysis of incidental word learning found, on average, that simply reading will enable students to learn 15 percent of the unknown words they encounter. These averages are tempered by grade level, reading level, and the density of text, but even fourth graders had the probability of learning 7 percent of the unknown words that they read independently. So, fourth-grade students reading 100,000 words independently (in books where 95 percent of the words are familiar) are learning approximately 350 words from the mere act of reading this many words (Swanborn & de Glopper, 1999).

WORD CONSCIOUSNESS

Word consciousness is an appreciation and understanding of the power and uses of words as tools of communication. It is the metacognitive or metalinguistic knowledge that a learner brings to the task of word learning (Anderson & Nagy, 1992; Graves & Watts-Taffe, 2002; Scott & Nagy, 2004). When we’ve talked about word consciousness in other books and articles, we’ve talked about “marinating” children in rich language experiences. Part of this is exposure to massive amounts of rich oral and written language. Another aspect, however, is making students aware of how the language of schools might differ from their home language, learning how to express themselves more powerfully in academic language as an addition to their home language, and gaining knowledge of how language patterns work in general. This is the fruits and vegetables level of the pyramid that deserves significant attention in a word learning program. Many of us need to add this element, like fruits and vegetables, to our daily diet. Much like developing art appreciation and music appreciation, developing an appreciation for the power of words and consciousness awareness of words is an attitude and stance that permeates our interactions regarding language each and every day.

Chances of learning words increase if students pay attention to the words they encounter in reading, in listening, and in the world around them. This conscious attention can be fostered by teachers and parents when they nurture students’ awareness about words as tools of communication, and awareness of how the English language packages word meanings. Knowledge about words is something that adult native speakers use almost automatically to figure out new word meanings (Nagy & Scott, 1991). However, there are elements of morphology, syntax, and the understanding of linguistic characteristics of words that can help students learn about sets of words and how to identify particular linguistic patterns. Learning words in sets by becoming conscious of these patterns will help students acquire not just specific words but also a facility to learn words in general (Scott & Nagy, 2004). Developing word consciousness involves coaching students in how words function and in how different words function differently to convey meaning. When someone wants to go with another person to lunch, a coworker might say to a colleague, “Can I come too?” or, on a more formal occasion, “Would it be appropriate if I attended as well?” However, a young child might say, “I wanna go!” Knowing when and how to use these different forms of language, as well as grasping the subtle differences conveyed by the syntax and word choice, is part of understanding the complexity of language. Helping students become conscious of these differences, and helping them realize how words are related to one another morphologically and semantically, is critical to both understanding and using sophisticated academic language (Baumann, Kame’enui, & Ash, 2003; Graves, 2000; Graves & Watts-Taffe; Scott, 2004; Scott & Nagy, 2004).

PROBLEM SOLVING

The problem-solving level of word learning is the dairy and eggs level of our program. It deserves a few servings each day and adds protein to our diet.

There are several strategies available for figuring out unknown words. For some words, you can use word parts to figure out the meaning (such as houseboat, jumped, unhappy). In other contexts, the author defines the word in the text. It is also sometimes appropriate to use a dictionary. We need to teach these problem-solving strategies to students so that they can use them independently when they encounter words they don’t know. In addition, we need to explicitly teach students how to read and use tools such as dictionaries and a thesaurus.

When we focus on word learning, we often tell teachers to teach context clues. However, learning how to use context clues is not as simple and straightforward as it might seem. Using such clues involves making inferences, figuring out which meaning of a word is appropriate and which aspect of the text is salient to the word in question. Problems also arise because context can be misleading at times (Robbins & Ehri, 1994; Schatz & Baldwin, 1986). However, there are ways to focus students’ attention on problem-solving techniques that are worth doing on a regular basis. These techniques should be taught explicitly and then developed throughout the year.

Dictionaries can provide explicit information about a word’s meaning that is normally only implicit in context. However, like dairy and egg products, they can be overused. The weakness of dictionaries is that they are poor tools for teaching school-aged children the meanings of new words. Miller and Gildea (1987) studied the sentences children generated when given definitions of unfamiliar words and concluded that this widely used task is pedagogically useless. For example, students take a definition such as the one for erode, meaning: “to eat out or eat away dirt,” and create a sentence such as, “My family erodes a lot.” Even when definitions were revised to enhance clarity and accuracy, student generated sentences were judged acceptable only half of the time (McKeown, 1993). Scott and Nagy (1997) found that the difficulty children experienced in interpreting definitions was primarily due to their failure to take the syntax or structure of definitions into account. Their errors reflected the selection of a fragment of a definition as the meaning of an unknown word, and half of the students were unable to make basic distinctions, such as whether the word was a noun or a verb, from a dictionary entry. Therefore, it seems important to teach students to use this tool well and to use it in small doses.

WORDS

Words are the meat of any vocabulary program. As important as it is to teach individual word meanings, we hope that you now realize the base that underlies this teaching. When we think of learning vocabulary, the individual word level is often the only one used or developed. Our program sees explicit teaching of individual words as critical, particularly in relationship to content area material. However, a diet of meat alone is not only boring but also unhealthy. We suggest that a balanced vocabulary diet contains problem-solving strategies, word consciousness, read alouds, wide reading, and rich oral language in addition to a singular focus on individual words. In fact, the more these elements can be combined in a complex and spicy meal, the more interesting word learning will become to our students.

We will come back to this basic pyramid throughout the book as a metaphor for how much and how often various activities should occur in different grades. In the next section, we’ll discuss why we think this metaphor works in greater depth, given our current understanding of the nature of word learning.

![]()

2

The Nature of Word Learning

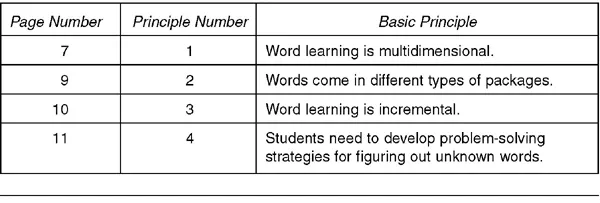

Figure 2.1 Basic Principles

If you recognize and understand the nature of word learning, you will be in a better position to teach vocabulary appropriately. This is much like knowing a few of the basic facts about cooking. Many cooks realize that you need a leavening agent to make bread rise, that egg yolk or oil will ruin a meringue, and that mixing fat, flour, and liquid properly eliminates the problem of lumpy gravy. These reactions are based on chemistry. Understanding the...