![]()

PART I

The Challenge of

School Decline

Every principal fears that he or she may be confronted with circumstances that can lead to school decline. No educational leader wants to have student achievement and a school’s hard-earned reputation plummet during his or her watch. This section looks at the conditions that can cause academic performance to drop and the leadership needed to prevent it. Being able to recognize the signs of incipient decline obviously is an important part of the process. Among the potential causes of school decline are shifts in the makeup of the student body, budget cuts, and changes in school culture. To the public, however, blame for school decline is often attributed to principals’ failure to address these challenges effectively.

![]()

1

Recognizing the Potential for School Decline

A SCHOOL ON THE BRINK*

Eli Buck reflected back on what might have been. Waverly Elementary School entered the 21st century as one of Westville’s premier elementary schools, but just how long its reputation could be maintained was open to considerable local conjecture. Since the late 1990s, the Hispanic population of Westville had steadily climbed. The region once welcomed the children of middle-class immigrants, but times had changed. Increasingly, those who came from beyond U.S. borders were poor and not well educated. Many were illiterate in their native language.

Some longtime residents of Westville worried that the influx of immigrants would tax the school system and other public services, eventually leading to an exodus of longtime residents and a loss of property value. At one point in 2005, Westville gained national notoriety when the city council passed an ordinance to prevent “overcrowding” of local residences. The measure clearly was intended to curtail Hispanic residents from housing extended family members and unrelated “guests.” Faced with threats of lawsuits from the American Civil Liberties Union and other organizations, the city council eventually backed off strict enforcement of the ordinance, but the message had been communicated. The welcome mat was not out for poor immigrants in Westville.

It did not take Eli Buck long to realize the high level of concern in the community. Soon after he became principal in June of 2004, he adjusted the marquee in front of Waverly Elementary so that messages were posted in English and Spanish. The complaints from concerned citizens were so vociferous that he felt compelled to return to English-only messages.

Several members of Buck’s faculty also registered their concerns about Waverly’s “changing demographics.” Several veteran teachers made it clear that they had no intention of modifying their instructional practices to accommodate immigrant students. Most of Waverly’s 50 teachers, however, seemed willing to do what they could to adjust to the new students, but they acknowledged their lack of adequate training. The Waverly faculty had received no site-based professional development for the previous five years. Many of the teachers had taught at Waverly for 10 or more years, well before the dramatic increase in non-English-speaking students. Teachers expressed frustration at the difficulty of communicating with parents who spoke little or no English.

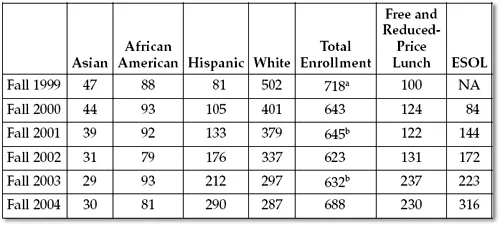

Table 1.1 indicates the extent to which Waverly had become a school with a diverse student population. Not surprisingly, the percentage of students on free and reduced-price lunch had increased along with the percentage of Hispanic students. By 2004, over one-third of the students came from low-income families. When Buck took over as principal, the upper grades still were predominantly non-Hispanic, but the lower grades already consisted primarily of Hispanic students.

Table 1.1 Student Demographics, 1999–2004

NOTE: ESOL = English for speakers of other languages.

a. Includes sixth grade. School became K–5 beginning in Fall 2000.

b. Native Americans are included in Total Enrollment

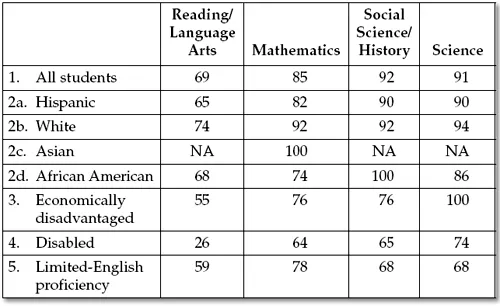

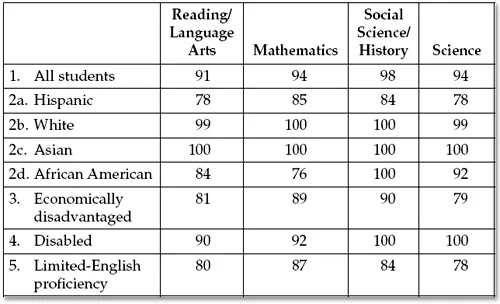

Buck could see the challenge before him when he examined the passing rates on state tests in reading/language arts, mathematics, social science/history, and science. Tables 1.2 and 1.3 contain the test data for third and fifth grades. A gap in passing rates between white and Hispanic third graders was evident, but what really troubled Buck was the fact that the gap widened for fifth graders. In other words, the longer Hispanic (and African American) students remained at Waverly, the less well they achieved relative to white students. Buck wondered what was happening at his school to contribute to the widening achievement gap.

Table 1.2 Percentage of Students Passing State Tests in Adequate Yearly Progress Categories, 2003–2004; Third Grade

Table 1.3 Percentage of Students Passing State Tests in Adequate Yearly Progress Categories, 2003–2004; Fifth Grade

In addition to needing to address the daunting challenge of narrowing the achievement gap between white and minority students, Buck faced a bevy of practical problems. His school, for example, lacked sufficient instructional space to house the growing number of Title I and English as a second language (ESL) teachers. Another concern involved the practice of retaining at grade level low-achieving students. Some of Waverly’s teachers strongly favored retention, but Buck understood that the effectiveness of this practice was questionable. This difference of opinion reflected a third issue. Buck believed that teachers should play an active role in school-based decision making. Knowing, however, that many members of his faculty held positions in opposition to his own beliefs, he wondered if he could afford to invite teacher participation in decision making. For their part, many teachers seemed reluctant to assume a leadership role in their grade level or at the school. Buck’s predecessor had done little to nurture shared decision making.

Of all the tough issues facing Buck, however, perhaps the toughest involved the parents of his white students. Many of these parents were clearly alarmed that their children were no longer in the majority in lower-grade classrooms. They bluntly asked Buck why they shouldn’t withdraw their children and move to a less diverse school.

DETECTING VULNERABILITIES

Every principal, like every physician, must be a good diagnostician in order to be effective. Good diagnosticians look at a range of conditions, not just the immediate problems that are presented to them. The challenges facing principals in the 21st century are likely to have organizational, social, political, legal, interpersonal, economic, and cultural, as well as educational, dimensions. The likelihood of addressing a challenge successfully is reduced when particular dimensions are overlooked.

The central challenge that confronted Eli Buck involved the fear that his school was poised on the brink of decline. Decline, in this case, refers to lower academic performance as indicated by falling passing rates on state standardized tests. Students of school decline understand that the process can be triggered by a variety of factors. In Eli Buck’s case, the potential precipitant was an influx of Hispanic students with serious educational needs. Other “triggers” to school decline include inadequate funding, weak leadership, and changes in school culture. These challenges will be addressed later in the chapter.

The consequences of failure to address the prospect of lower academic achievement can be very serious. Some have characterized the result of such failure as a downward spiral in which the rate of decline steadily accelerates (Duke, 2008a). Falling test scores, for instance, can lead to parental concerns, which in turn can cause some parents to withdraw their children and send them to other schools. The consequence is a loss of resources that can lead to a reduction in staff. If the students who are withdrawn tend to be higher achieving students, then the concentration of lower achieving students grows, thereby increasing the workload for the remaining teachers and the likelihood of a continuing drop in academic achievement. Such circumstances are likely to cause plummeting teacher morale and a voluntary exodus of additional staff. Recruiting new teachers to fill openings is certain to be difficult, adding to the prospect of sustained school decline.

Whether Eli Buck foresaw all of these possibilities or not is unclear, but he clearly grasped the fact that the challenge facing him was multidimensional. Among the factors he realized could contribute to Waverly’s decline if they went unaddressed were the following:

- Lack of instruction geared to the needs of newcomer students

- Overreliance on retention as an intervention

- Reluctance of teachers to assume leadership roles

- Concerns among white parents

- Difficulties concerning home-school communications with Hispanic families

Buck did not blame teachers for lacking the skills to teach students with limited ability in English. Waverly, after all, had lacked any kind of professional development aligned to the needs of its new students. What really concerned Buck, however, was the unwillingness of some teachers to embrace the need for changes in their instructional practice. In certain cases, veteran teachers who had experienced great success in the past remained convinced that their approach to teaching was appropriate for all students. They expected new students to make the adjustment to their instruction, not the reverse. Buck wanted to point out that much of these teachers’ prior success could be attributed to who their students were, not how they taught.

Some teachers even felt it was not their responsibility to teach the new students. That was what Title I and ESL teachers were expected to do. Relying on pull-out programs, Buck knew, had its downside. When students left class to get help from specialists, they ran the risk of falling further behind their classmates. Prolonged absence virtually ensured that these students would never catch up. Over time, students who were retained in elementary school were more likely to have problems in middle school and eventually drop out of high school. Buck also realized, though, that promoting low achievers to the next grade was unlikely to be successful if their teachers lacked the skills to address these students’ learning needs.

Given the large number of veteran teachers at Waverly and Buck’s belief in teacher leadership, he wanted to enlist faculty members in the effort to avoid school decline. No principal by himself or herself can handle all the changes required to accommodate an increasingly diverse student body. Teamwork was the key, but Buck discovered that most Waverly teachers were reluctant to serve as team leaders or assume other leadership roles.

The last two factors that had to be addressed if school decline was to be averted involved Waverly’s parents. White parents needed reassurance that efforts to respond to increasing student diversity would not result in their children’s education being compromised. Fearing that Waverly teachers would have to spend most of their time with non-English-speaking and limited-English-speaking students, white parents threatened to send their children to other schools. Buck knew that “white flight,” if it did occur, would not serve the academic interests of the students who remained at Waverly.

The other group of parents whose concerns had to be addressed was Hispanic parents, but the language barrier presented a formidable obstacle. There were few Spanish-speaking staff members at Waverly. The limited English of many parents made them reluctant to approach teachers with their questions and concerns. Without the active involvement and support of these parents, the challenge of providing their children with a sound education would be even greater.

Before a principal can address a challenge like the threat of school decline, he or she has to diagnose the school-based conditions that may need to be changed. The potential for incorrect diagnoses, of course, is ever present. There is no substitute for good listening skills, sound judgment, willingness to question standard operating procedures, and a commitment to doing whatever is necessary to serve the interests of children. Eli Buck possessed all of these attributes, and they helped him determine the leadership focus needed to address an increasingly diverse student body.

School decline, of course, may result from other impetuses besides changing demographics. In the following sections, three other decline scenarios will be discussed.

THE IMPACT OF INADEQUATE FUNDING

Economic conditions are roller coasters for public institutions like schools. When the local, state, or national economy sneezes, schools catch cold. The relationship between school funding and student achievement is well established (Darling-Hammond, 1997; Flanagan & Grissmer, 2005). In Savage Inequalities, Kozol (1991) provides disturbingly vivid examples of how funding disparities place students in poor school systems at a decided disadvantage. Even students in relatively well-off school systems may face the prospect of academic adversity when there is a downturn in the economy or a substantial loss of school funding. Such was the case in San Jose, California, following the passage of Proposition 13 in 1978 (Duke & Meckel, 1980).

Proposition 13 restricted the ability of localities in California to raise revenues by increasing property taxes. Since a substantial portion of school funding came from local property taxes, the impact was immediate and far-reaching. Stanford University researchers reported on how two consecutive years of 10 percent budget cuts affected one high school in San Jose (Duke & Meckel, 1980). It should be noted that the principal did not control all of the ways that the budget cuts were made. Some of the retrenchment decisions were governed by district policies and the teachers’ contract. The principal, however, was expected to minimize the impact of all budget cuts on teaching and learning.

In 1979, the first year that Proposition 13–related cuts were implemented, San Jose High School enrolled 1,400 students, 65 percent of whom was Hispanic. Another 15 percent consisted of African American, Portuguese, and recently arrived Vietnamese students. Many students qualified for free and reduced-price lunch. Despite the principal’s pleas that San Jose High School should not be cut as much as high schools in more affluent parts of the district, the central office insisted that all school budgets would be reduced by the same percentage.

To absorb the first round of cuts, San Jose High School released 14 teachers. They were collectively responsible for 44 classes. So great was the loss of classes, in fact, that the principal had to switch the schedule from a six-period to a five-period school day. This move had the immediate effect of limiting the course options available to students, eliminating teachers’ planning periods, and increasing class sizes. The teacher-student ratio jumped to 1:31. More than 20 paraprofessionals also had to be released. Many of them came from the local community and spoke Spanish. Their departure meant the loss of a vital link between the school and non-English-speaking parents. The district even pressed the principal to eliminate the entire counseling department, but he was able to retain five counselors on the condition that each would teach several classes.

To accommodate the loss of faculty, six sections of English as a Second Language were dropped. An innovative reading remediation program was scaled back, and electives in music and industrial arts were eliminated. In most of these cases, the principal had little choice. Courses required for graduation could not be dropped. Seniority rules in the teachers’ contract sometimes resulted in fully qualified teachers being “bumped” by less qualified but more senior teachers from other schools in the district. Eleven veteran teachers were transferred to San Jose High School in the fall of 1979. Under normal conditions, transfer teachers with limited experience teaching certain courses would be assisted by department chairs. Department chairs, unfortunately, also had been eliminated as part of retrenchment.

No area of school operations was spared. Extracurricular activities took an especially big hit. The band was disbanded, and approximately half of the sports program was cut. Physical education offerings also were curtailed.

Even the most capable principal may be unable to protect students and teachers from all the adversities associated with the kind of drastic cuts faced by San Jose High School. What principals must do to minimize the negative impact of such cuts is to anticipate where and how the reductions will be felt. This is an important aspect of organizational diagn...