![]()

![]()

Historiography

Photographs of the elderly post-World War II immigrants and their houses illustrate a picture-history of immigrant-receiving nations that is rarely presented in scholarly or mainstream publications. For the settler nations – Canada, North America, Australia and New Zealand – this is not the ubiquitous image of the pioneer in front of their colonial homestead, or their frontier shack, nor the image of the workers’ cottages with their first inhabitants, nor the image of the nuclear family and the quintessential post-war 1950s suburban house. Architectural historiography does not traditionally include people in its visual representation, but these post-war immigrant subjects were not accounted for in the critical architecture perspectives of the 1960s, which espoused a people-oriented approach and experimental representation.1 Also, immigrants were not integral to the representation of the housing that evolved out of the welfare state in post-war Europe. Vast industrial sites and economic growth was built on the back of immigrant labour and yet European nations deny they were immigrant nations. The social housing agenda in progressive societies such as Sweden did not include representations of immigrant families in their promotional material of the new Swedish citizen. The housing of elderly post-war migrants is testimony to the longevity, rather than arrival, of migrant settlement and their contribution to community. The ways migrant housing has shaped migrant belonging, neighbourhoods and new transcultural societies requires alternative conceptualisations of both migration and architectural history.

Historiography is a specific version of the past. Housing historians have not extended their research interest to the housing of post-war immigrants. Such an omission contrasts with the way food is celebrated in post-migration multicultural societies, and how migrants have been directly linked to enrichening the cuisines of immigrant cities. Food is consumable, digestable, but architecture and housing constitute settlement and permanence, and are linked to property, territory, finance and laws, and shaping the physical and symbolic environment.2 Pictures of post-war immigrant housing and the settlement realities of post-war immigrants are not able to be reconciled with national labour and migration policies. Sociologist, Pierre Bourdieu’s statement, ‘taste classifies, and it classifies the classifier’, points to the delicate subjectivity involved in writing and picturing history.3 The historian’s labour towards objectivity and the non-personal is traditionally developed through detailed methodology and evidence, but the best of historians have to pass by the subjectivism of taste and process its dominant paradigm and its individual affect in order to see a different picture of history; and also to see the many histories and realities, rather than the many perspectives of the one history.

The photographs of elderly immigrants and their houses present challenges to both migration and architectural readers because the images may be seen as obtuse and distant, and because they do not resonate within the familiar fields of our knowledge and discipline. In other words, images are perceived as either intelligible or not intelligible, depending on the reader’s level of familiarity or interest and how their analytical apparatus can engage with the subject. The details the images portray present further challenges. Post-war immigrants have aged and become elderly in their country of settlement. Photographs taken decades after their arrival are not static artefacts, but resonate with temporal struggles, battles and evolutions.4 In that time post-war immigrants have adapted, extended or built houses.

House Turquoise and House Bitola shown in Figure 1.1 are existing housing typologies altered and adapted by the migrants. Atanas, who emigrated from Lerin in Greece, arriving in Australia in 1969 after migrations to Canada and France, has lived in his house for over thirty years. House Turquoise is a small single-fronted timber workers’ cottage typical of the style of timber row housing imported from England and built in the early 1890s.5 Kliment and Svetlana emigrated from Bitola in the Republic of Macedonia in 1968 and have lived for over thirty years in their House Bitola, a small double-fronted weatherboard ‘Californian Bungalow’ built circa 1920s. Atanas, Kliment and Svetlana are not typical migrant success stories that reflect a progressive housing trajectory from the inner-city suburbs of Melbourne to newly built houses in middle and peripheral suburbs. They remained and lived in the first old house they were able to purchase, continually repairing and altering, but not reconstructing their house. Sotir and Agnia emigrated from Lerin in Greece in 1954. After building a brick veneer house in Northcote, they moved to a distant suburb but soon returned to purchase the house built by Italian migrants in 1962, an orange brick veneer house, House Aegean (see Figure 1.1). Atanas, Kliment and Svetlana, and Sotir and Agnia, are working-class immigrants of Macedonian ethnicity. They speak Macedonian at home and to their children. They have lived in the same house for a long time. Like other Australians, they have adapted their houses, but neither their housing stories or the histories of migrant housing are part of how Australian housing is represented in the national narratives of Australia.6

Migrant housing reveals that immigrants are not temporary inhabitants, but residents and citizens of their adopted nation. Despite the focus on economic growth, many, if not all post-war societies, are formed and contingent on the long-term sociocultural impact of post-war labour migration. Culture, ethnicity, identity and plurality evolved as new discourses out of histories of post-war migration, and have redefined knowledge, charting research on belonging, home and community. And yet the images of elderly immigrants and their houses rarely resonate with a national ‘we’ that is collectively pictured, narrated or represented. Instead, the images are cast as intrinsically controversial or confronting. In addition, the history of migration discourse is devoid of the debates about architecture as if such a static reference disturbs the narrative of migration as relentless unsettlement.7 This representation confines migration discourse to a timeframe of immediacy driven by the hot topics of a migrant crisis in the daily newspapers. Visual images require intellectual investment if they are to document a history of migration and architecture, or the images risk being marginalised and ignored.

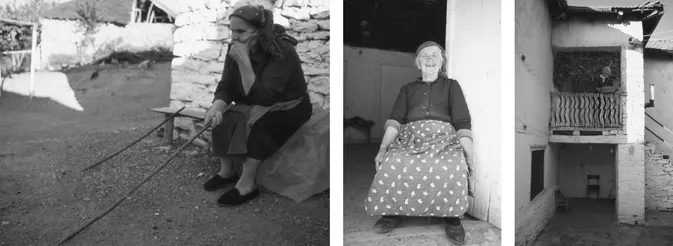

Most at risk of obliteration are the images of the elderly that have remained in homeland sites after the effect of mass emigration (see Figure 1.2). Abandoned villages are dotted all over those parts of the world that sent labour migrants to the nation-building programmes of advancing economies in the post-war period.8 The history of post-war industrialisation and modernisation is equally the history of labour emigration from southern Europe, a historical south that is overlooked in the current framings of the ‘global south’.9 Labour migrants, extracted from the economically depleted rural zones of southern Europe, submitted their able bodies to the industrial economies of central and northern European states.10 Villages in much of southern Europe – Italy, Greece and Yugoslavia, as well as Portugal and Spain – were emptied of nearly all their young healthy workers. Histories of post-agriculture working-class emigration run parallel with the growth of powerful economies, on the one hand, and acute under-development of emigrant nations, on the other.11 A much broader network of villages subjected to the mass emigration of their inhabitants enter histories of abandonment and neglect, sometimes followed by investment and material changes that results in estranged remittance landscapes comprising incomplete structures left empty, closed and unused.

Migrant housing in the city, Melbourne forms a dialectic with the architectural transformation of the village, Zavoj in the Republic of Macedonia. Dola, Polka and Petra, women that remained in Zavoj, spoke about the hard work, poverty, marriage and family, and after a moment’s silence and then laughter, mentioned their secret pleasure of walking alone in the mountains (see Figure 1.2). They were pinned to their remote village at the top of the mountain, elderly and forgotten by the world. But the three women preferred to live in the village on their own even after their husbands passed away, rather than with their sons or daughters in the town. Contrary to popular perception, they have not led simple parochial lives, many have visited the towns, and some have lived abroad in the immigrant cities of their children. Srebrejca, described her impressions of Melbourne and the housing of its suburban environment while visiting her daughter, as ‘затвор’, or ‘prison’, stating emphatically, ‘always locked up inside, nowhere to walk’. She returned to her village expressing why she prefers to live there: ‘Kaj sakas si setas [кај сакаш си шеташ]’. ‘Here we can go anywhere. If you want to go to the top of the village, down to the creek, if you want to go into the hills, we’re not afraid to go into the hills, we’ve learnt about this.’12

In the village, women have stayed alone in the traditional houses for large parts of their working lives; these women are widows in black. Men eventually returned to the village following their labour sojourn and rebuilt a hybrid rural–urban life. These women and men move with the agility of those who are invisible to the contemporary world and its fast-paced economies. In the first comprehensive fieldwork in 1988, the entire village was measured, documented and recorded in plan form. Architectural documentation of houses, structures, barns and sheds, as well as half walls, sapling fences and wooden gates revealed how materiality was interwoven with social space.13 Subsequent fieldwork in 1996, 2002, 2005, 2007, 2010, 2013, 2015 and 2017, comprising the documentation of the transfo...