Italy’s permanent crisis – which started in 1992

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008, the Italian economy went through years of economic stagnation and decline, suffering three “official” recessions in a row. Italy’s third recession in a decade started in the last two quarters of 2018, following a slowdown in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth throughout the Eurozone. In response to the third recession, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Central Bank (ECB) lowered their growth forecasts for Italy for the next several years to come to negative numbers, and, in what analysts see as a precautionary move, the ECB is currently reviving its sovereign bond buying programme, which it had started to unwind as recently as December 2018. “Don’t underestimate the impact of the Italian recession,” is what the French Minister of the Economy and Finance Bruno Le Maire recently told Bloomberg News (Horobin, 2019). He goes on to say that “We talk a lot about Brexit, but we don’t talk much about an Italian recession that will have a significant impact on growth in Europe and can impact France, because it’s one of our most important trading partners.” More importantly than trade, however, and what Le Maire is not stating here, is that the French banks are holding around €385 billion of Italian debt, derivatives, credit commitments and guarantees on their balance sheets, while the German banks are holding €126 billion of Italian debt (as of the third quarter of 2018, according to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS, 2019)). In view of these exposures to Italian debt, it is no wonder that Le Maire, and the European Commission (EC) too, is worried by Italy’s third recession in a decade – as well as by the growing anti-euro rhetoric and posturing of Italy’s coalition government consisting of the Five-Star Movement (M5S) and the Lega.

It is therefore vital to understand the true origins of Italy’s economic crisis – and for this, we have to go back in time to the 1980s and early 1990s, when the Italian state committed itself to fiscal consolidation and structural (labour market) reforms in order to be able to join the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). In this chapter, I provide an evidence-based pathology of Italy’s long-term recession – which, I argue, must be regarded as a crisis of the “post-Maastricht Treaty order of Italian capitalism,” as Fazi (2018) calls it. Up until the early 1990s, Italy enjoyed decades of relatively robust economic growth, during which it managed to catch up in per capita income with the other Eurozone nations. But then a very steady decline began, erasing decades of (income) convergence. The per capita income gap between Italy and France is now (in 2018) 18 percentage points, which is more than what it was in 1960; Italian GDP per capita is 76% of per capita GDP in the Euro-4 (Belgium, France, Germany and the Netherlands) economies (see Storm, 2019). Beginning in the early to mid-1990s, the Italian economy began to stumble and then fall behind, as all main indicators – per capita income, labour productivity, investment, export market share, etc. – began a very steady decline. Italy’s deep crisis is perhaps illustrated best by the 15% decline in annual net income (at constant 2010 prices) of the median household – from €27,499 in 1991 to €23,277 in 2016; mean net household income fell by 10% between 1991 and 2016 (Brandolini et al., 2018). Italy is the only major Eurozone country which, in the past 27 years, has suffered not stagnation but decline. All income classes – poor and rich alike – suffered, but the poor suffered more than the rich and hence income inequality, measured by the Gini coefficient, which came down during the 1980s, increased in the 1990s. According to the Bank of Italy Survey on Household Income and Wealth (Table S49), the Gini coefficient rose from 0.288 in 1991 to 0.330 in 2000 and 0.335 in 2016 (Banca d’Italia, 2019).

It is not a coincidence that the sudden reversal of Italy’s economic fortunes occurred after Italy’s adoption of the legal and policy superstructure imposed on it by the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, which cleared the road for the establishment of the EMU in 1999 and the introduction of the common currency known as the “euro” in 2002. Italy, as I show below, has been the star pupil in the Eurozone class, the one economy which committed itself most strongly and consistently to the fiscal austerity and structural reforms which form the essence of the EMU macroeconomic rulebook (Costantini, 2017, 2018). Italy kept closer to the rules than both France and Germany and paid heavily for it: permanent fiscal consolidation, persistent wage restraint and an overvalued exchange rate killed Italian aggregate demand – and the ensuing demand shortage asphyxiated the growth of output, productivity, jobs and incomes (Cesaratto and Stirati, 2010; Cesaratto and Zezza, 2018; Storm, 2019).

Italy’s stasis is an object lesson for all Eurozone economies, but – paraphrasing G.B. Shaw – as a warning, not as an example. As I argue below, the chronic shortage of demand was created by (a) a policy of perpetual fiscal austerity; (b) permanent real wage restraint; and (c) a lack of technological competitiveness which, in combination with an unfavourable (euro) exchange rate, reduced the ability of Italian firms to maintain their export market share in the face of increasing competition from low-wage countries (China in particular). These three factors are currently depressing demand, reducing capacity utilization and lowering firm profitability; hurting investment, innovation, and productivity growth; and hence locking the country into a state of permanent decline characterized by the impoverishment of the productive matrix of the Italian economy and the quality composition of its trade flows (Simonazzi et al., 2013; Celi et al., 2018). I will now review the three causes of the aggregate demand shortfall in greater detail.

Perpetual fiscal austerity

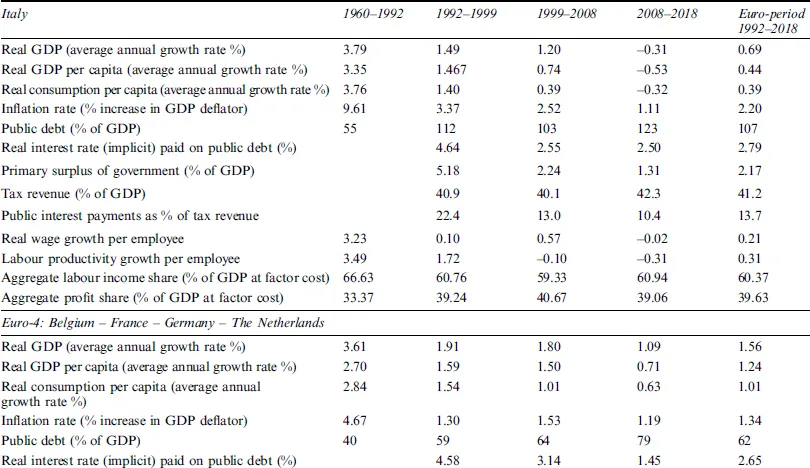

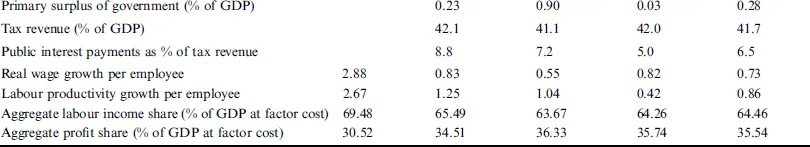

To allay fears that it could not and would not meet the policy conditions for membership in the EMU, specified in the Treaty of Maastricht, the Italian government did more than most other Eurozone member governments in terms of self-imposed austerity and structural reform in order to satisfy the conditions of the EMU (Halevi, 2019). This is clear when comparing Italy’s fiscal policy post-1992 to those of France and Germany. Various Italian governments showed remarkable commitment to fiscal consolidation and ran continuous primary budget surpluses (defined as public expenditure excluding interest payments on public debt, minus public revenue). The primary budget surpluses of the Italian state averaged 3% of GDP per year during 1995–2008 (Storm, 2019; see also Table 1.1). French governments, in contrast, ran primary deficits of 0.1% of GDP each year on average during the same period, while German governments managed to generate a primary surplus of 0.7% on average per year during those same 14 years. Italy’s permanent primary surpluses during 1995–2008 would have reduced its public-debt-to-GDP ratio by around 40 percentage points (Storm, 2019) – from 117% in 1994 to 77% in 2008 (while keeping all other factors constant). But slow (nominal) growth relative to high (nominal) interest rates pushed up the debt ratio by 23 percentage points and washed away more than half of the public-debt-to-GDP reductions of 40 percentage points achieved by austerity. Could it be true that Italy’s permanent austerity, which was intended to lower the debt ratio by running permanent primary surpluses, backfired because it slowed down economic growth?

Table 1.1 Growth and distribution: the Italian economy versus those of the Euro-4 countries, 1960–2018.

Even during the crisis years of 2008–2018, Italy’s governments (including the left-of-centre Renzi coalition) continued to run significant primary budget surpluses of more than 1.3% of GDP on average per year (Table 1.1). Showing permanent fiscal discipline was top priority, as Prime Minister Mario Monti (2012) admitted in an interview with CNN, even if this meant “destroying domestic demand” and pushing the economy into decline. Italy’s almost “Swabian” commitment to fiscal discipline stands in some contrast to the French (“laissez aller”) attitude: the French government ran primary deficits at an average of 2% of GDP during 2008–2018 and allowed its public-debt-to-GDP ratio to rise up to almost 100% in 2018. The cumulative fiscal stimulus thus provided by the French state amounted to €461 billion (in constant 2010 prices), whereas the cumulative fiscal drain on Italian domestic demand was €227 billion (Storm, 2019). The Italian budget cuts show up in non-trivial declines in the state’s public per capita social spending, which is now (in 2018) around 70% of public social spending per capita in Germany and France. One can only imagine what the Gilets Jaunes protests in France would have looked like had France put through an Italian-style fiscal consolidation post-2008.

Italy’s fiscal consolidation saw the growth of Italy’s real per capita public consumption expenditure, which had averaged 3% per year during 1960–1992, slashed to zero during the period 1992–2018. Real public spending growth had contributed 0.65 percentage points to Italy’s average annual real per capita GDP growth rate of 3.35% during 1960–1992, but contributed absolutely nothing to Italy’s real GDP growth after 1992. Next, we can look at gross public investment by the Italian state, which was growing at 2.5% per year during 1960–1992 and which contributed 0.15 percentage points to Italy’s growth during those years. However, during the period 1992–2018, Italy’s public investment declined by 0.5% on average each year in real terms – which is now showing up, on the supply side, in a decaying stock of public infrastructure (e.g. bridges, roads, railroads and tunnels). On the demand side, it lowered Italy’s average annual real GDP growth rate by 0.05 percentage points post-1992. Taken together, a conservative estimate of the growth impact of Italy’s fiscal consolidation is that the cuts in the growth of public consumption and investment depressed Italy’s per capita real GDP growth during 1992–2018 by 0.85 percentage points (Storm, 2019).