![]()

1

Introduction

The importance of renewable materials

The environmental damage caused by over-extraction of materials for human production-to-consumption systems has led to serious concerns about the Earth’s carrying capacity, and highlighted the importance of renewable materials. Almost three-fourths (70%) of the materials we use post-industrialization – such as coal, natural gas and oil – come from the lithosphere (Thorpe, 2007). These materials take millions of years to form and are therefore considered non-renewable, as opposed to resources from the biosphere, which take a comparatively shorter time to regenerate, and are therefore renewable (Thorpe, 2007).

Bio-based materials are more energy-efficient than most commonly recycled materials because their production generally requires less energy (Van der Lugt, 2017). Most plastics, though recyclable, are not in fact recycled because recycled plastic is generally more expensive and of lower quality than virgin plastic (Van der Lugt, 2017). Metallic minerals, like aluminum and steel, can be recycled with minimal or no change in quality; however, there is simply not enough scrap metal to meet worldwide demand (Van der Lugt, 2017).

Therefore, an important rule of thumb in sustainability design is to use renewable input materials (Crul & Diehl, 2006) from the biosphere – such as wood, cotton, linen, hemp and bamboo.

The decline of traditional production-to-consumption systems for craft based on renewable materials

Renewable resources from the biosphere – such as grasses and other natural fibers, vegetables and fruits such as coconuts and squashes, and animal-based materials such as leather and sea shells (Risatti, 2007) – have traditionally been used as input materials for craft-based production-to-consumption systems around the world, due their easy availability in the natural environment. Craftspeople spanning several categories – including:

the skilled master craftsman, the wage worker, the fully self-employed artisan, the village artisan producing wares for local use, the part-time artisan whose craft activities supplement his meager earnings from the land, and the landless artisan – have historically been, and still are, employed in crafting these materials into products for the use of their own communities or for trade and export.

(Jaitley, 2001, p. 14)

Post-industrialization, craft-based production-to-consumption systems – and the craftspeople they encompass – are endangered with the influx of industrial products into their traditionally closed economies (Jaitley, 2001). This is a spin-off of the industrial and information revolutions, each of which has impacted access and reorganized economic activity (Humbert, 2007) across the world. The physical and virtual connectivity of the information revolution has exposed consumers in developing countries – including rural buyers – to globalized lifestyles, to which they now aspire. This preference for technology over tradition (Chaudhary, 2010), and for mass-produced substitutes over craft products, has disrupted traditional localized production-to-consumption systems, resulting in a loss of livelihoods for traditional producers in developing countries – thereby contributing to poverty and unemployment.

The unsustainability of livelihoods for craftspeople, given their lack of economic or productive skills, assets and options apart from craft, has forced many indigenous craftspeople to migrate to urban areas in search of wage labor (Reubens, 2010a; Society for Rural, Urban and Tribal Initiatives, 1995). This causes unsustainability at several levels. Several crafts have either vanished or are declining, and the pressure caused by mass-migration and unprecedented urbanization (Craft Revival Trust, 2006) makes it difficult to even imagine the possibility of sustainable development for all.

The opportunity and need for design vis-à-vis sustaining craft-based production-to-consumption systems

Globalization, the information revolution and unprecedented development – the same constituents which contributed to the unsustainability of craft-based livelihoods – offer a way forward for their sustainability. These same three phenomena have catalyzed a growing demand for sustainable products (Potts, van der Meer, & Daitchman, 2010), including products crafted by communities (Ihatsu, 2002). Sustainability-aligned markets are expanding faster than markets for conventional products, and are increasingly embracing initiatives that factor in a wider spectrum of sustainability criteria – including ecological, social and economic considerations (Potts et al., 2010; Sustainable Brands, 2017).

Despite being a good match, traditional craftspeople in the developing world are unable to access and navigate emerging markets for sustainable products, to which developed and organized regions have privileged access (Potts et al., 2010). The reason for this disconnect is that craftspeople are unfamiliar with new globalized markets where the producer and buyer are physically disconnected. These markets are in stark contrast to traditional craft production-to-consumption systems which hinge on the craftsperson-patron connection. The link between buyer and producer was severed during the process of industrialization, when industrial concepts such as standardization and economy of scale heralded the need to divide the integrated craft-based production-to-consumption process into specialized disciplines (Dormer, 1997) – including design, production and marketing – to increase the productivity of each process, in line with the new concept of division of labor (Cusumano, 1991).

In contemporary globalized value chains, craftspeople are able to function as producers, but there are several gaps which need to be filled with supplemental players in the value chain: actors (who directly produce, process, trade and own the products), supporters (who do not deal directly with the product, but whose services add value to the product) and influencers (who create and moderate the regulatory framework, policies, infrastructure, etc., at the local, national and international levels) (Roduner, 2007). Identifying and putting in place these value-chain actors, supporters and influencers can help bridge the gap between craftspeople and sustainability-aligned markets.

Designers, who have traditionally functioned as the bridge between production and marketing, are ideally positioned to bridge the gap between craftspeople and sustainability-aligned markets. Designers are equipped with the skills and tools to envisage distant scenarios and innovate accordingly, a skill most craft-producer communities lack. Designers are also able to internalize industrial concepts, such as batch production, productivity and quality checks, needed to maintain these markets. For these reasons and more, designers can be instrumental in enabling craftspeople to leverage sustainability-aligned markets, and thereby sustain their livelihoods.

Why existing design initiatives for renewable materials overlook the craft-livelihood connection

Emerging design initiatives and approaches already look at leveraging sustainability-aligned markets, including in the context of developing countries. Several of these initiatives have an ecological focus (Reubens, 2013b). They look at recontextualizing renewable materials – including those traditionally used in non-industrial craft production-to-consumption systems, such as cork and bamboo – using industrial techniques and technologies to create innovative products and systems for sustainability-aligned markets. While the resultant designs contribute to ecological sustainability, they miss out on the chance to address the outcomes of complex and interlinked social, cultural and economic unsustainabilities – such as poverty and unemployment – in the developing countries where these products are produced. Consequently, they bypass the need and opportunity for design to be a vehicle to address the social, cultural and economic dimensions of sustainability alongside its ecological aspect.

A case in point to illustrate this would be that of the International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR), an intergovernmental organization which aims to improve global bamboo production-to-consumption systems, through its programs on climate change, environmental sustainability, poverty alleviation, sustainable construction, trade and development. INBAR aims to generate equitable incomes from bamboo and rattan, by extending value chains and building stronger partnerships between consumer and producer countries through a cross section of approaches, including supporting – and broadening the application of – technological product innovation (INBAR, n.d.). Towards this end, in 2006, INBAR supported Pablo van der Lugt – a Ph.D. researcher from Delft University of Technology, the Netherlands – in studying why bamboo products only have a small market share in the EU, despite the potential of industrially processed bamboo as a fast-growing substitute for hardwood. The resulting report, titled, Bamboo Product Commercialization in the West: A State-of-the-Art Analysis of Bottlenecks and Opportunities (Van der Lugt & Otten, 2010) indicated that design intervention could aid in a greater acceptability of bamboo in the West. To facilitate this, van der Lugt organized a series of design workshops to encourage Dutch designers to work with bamboo, under the project Dutch Design Meets Bamboo (Van der Lugt, 2007), as part of his research work. The prototypes developed during the project received positive media attention as eco-friendly designer products, and some were successfully commercialized.

These design-led, industrially processed, engineered bamboo products demonstrated that through design, non-mainstream renewable materials could find commercial viability in sustainability-aligned markets. However, recent studies (Bailly, 2010; Williams, 2007) have questioned the ecological sustainability of these products, given their huge carbon footprint if they are transported from producers in developing countries to markets in developed countries. In addition to the energy spent in transportation, the energy used in producing engineered bamboo also increases its carbon footprint – in fact, even more so than transportation (Van der Lugt, 2017).

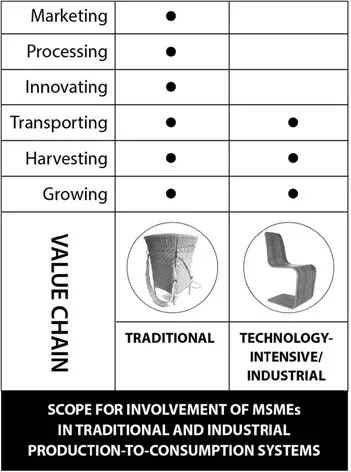

In addition to perhaps not being as ecologically sustainable as first imagined, industrially processed, engineered products also fail to leverage bamboo’s potential to contribute to social and cultural sustainability by addressing issues of poverty and livelihoods (Lobovikov, Paudel, Piazza, Ren, & Wu, 2007). This is because these products do not translate into livelihoods for indigent bamboo producers in traditional MSMEs (micro, small and medium enterprises) in Asia, Africa and Latin America, where a substantial percentage of bamboo production takes place. These communities lack the financial capital to invest in the technology that these product lines require. Therefore, they go from being involved in, and therefore benefitting from, every node of non-industrial bamboo value chains to having limited involvement in industrial value chains – mostly in growing, managing, harvesting, transporting and processing bamboo at the most primary levels (Figure 1.1).

The scenario just discussed is not specific to bamboo. It is common to the value chains of several renewable materials – including cork, sea grass, rattan, hemp and jute – especially those which have traditionally been part of craft production-to-consumption systems. This sheds light on the fact that design efforts – even if aligned to sustainability markets and involving green materials – need to go beyond green design and commercial viability, if they are to impact all the dimensions of sustainability in a balanced and holistic manner. To achieve this, there is a need to bridge the worlds of development and design, and to facilitate design which actively seeks to impact sustainability holistically in the context of developing world enterprises.

Figure 1.1 Involvement of poor-producers in traditional and technology-intensive/industrial value chains

The need for sustainable alternatives to the traditional industrial design paradigm

Design for and in developing countries can be instrumental in realizing a holistically sustainable vision of development. Such development would rest on economic development, with a simultaneous increase in socially desirable phenomena (Lélé, 1991), and would also be mindful of ecological and cultural aspects. Design has already been able to align the renewable raw materials available in developing countries with sustainability markets – including, as discussed earlier, by using industrial processing to reconstitute these materials into new avatars. Though these new designs capitalize on sustainability markets, they do not leverage the huge workforce and cultural resources available in developing countries. Nor do they realize design’s potential to orchestrate production-to-consumption systems which contribute to holistic sustainability, by simultaneously addressing social, cultural, economic and ecological dimensions, and their complex interlinkages. In order to do this, design needs to facilitate production-to-consumption systems that are underpinned by technologies which have a high potential for employment, are not capital-intensive, and are highly adaptable to social and cultural environments (Jequier & Blanc, 1983). This, in turn, calls for design to challenge mainstream, technology-intensive industrial design approaches, which do not tackle the concept of sustainability in a holistic manner (Maxwell, Sheate, & van der Vorst, 2003). This is easier said than done, as the design-industrialization bond is deeply rooted; the discipline of design emerged as a result of the process of industrialization, and therefore inherently aligns to industrial logic and philosophy. This highlights the need for alternatives to mainstream design approaches which generate collective benefits to the ecology, society, economy (Maxwell et al., 2003) and culture in the context of developing countries.

This book focuses on this underexplored area and aims to improve sustainability design approaches, and thereby practice – especially in the domain of enterprises working with renewable materials in developing countries.

Sustainability is a new and emerging field, and offers no comprehensive answers yet. Therefore, we center on three main questions in this book:

- To what extent does design address sustainability holistically – simultaneously considering all of its dimensions including social, economic, ecological and cultural dimensions – while working with non-industrial craft-based enterprises working with renewable materials in developing countries?

- What could be a possible sustainability design approach that: a) is mindful of the pros and cons of the existing sustainability design approaches, and b) looks at addressing a holistic picture of sustainability – including its ecological, social, economic and cultural dimensions – in the context of non-industrial craft-based MSMEs working with renewable materials in developing countries?

- What mechanisms would support and encourage the use and operationalization of a sustainability design approach that might be identified or developed in response to Question 2?

Our primary objective is to improve sustainability design practice so that it positively impacts sustainability in a holistic manner, especially in the case of craft-based enterprises in developing countries (Question 3). This question is underpinned by the existence of a sustainability design approach that better addresses sustainability holistically (Question2) and is mindful of existing scholarship and practice in this regard (Question 1).

The first step into our inquiry is to understand what exists – to what extent current design approaches to achieve sustainability address the topic holistically (Question 1). Chapter 2 focuses on exploring and crystallizing the concept of sustainability, based on which, chapter 3 explores current design approaches to actualize sustainability: what exists – including why and how it occurs.