The popular thinking that the Constitution is a gift from the throne locates and acknowledges the throne, particularly the Fourth King as the source of legitimacy as well as agency for Bhutan’s historic democratic transition. However, he had said: “[t]he Constitution should not be considered as a gift from the King to the people: it is my duty to initiate the constitutional process so that our people can become fully involved in shaping and looking after the future destiny of our country.”3 Hence, from the very beginning, the King conveyed the idea that while he would initiate the constitutional process, it is the people and their representatives who would draft the Constitution. The King intended to locate the legitimacy of the Constitution in the people.

There was thus two ways to think about assigning the source of legitimacy for Bhutan’s first written Constitution. The King placed it in the people, and the people in the King. How did the King embed the legitimacy for the Constitution in the people and the people conceptualised the Constitution as the King’s gift? He had commanded the drafting of the Constitution on 4 September 2001 by issuing a decree to the government:

While His Majesty gave a broad directive, enunciating the basic and progressive democratic principles, Lyonpo Sonam Tobgye4 said that His Majesty was cognizant of the fact that the members of the drafting committee must be broad-based and that they must be elected so that there will be a voice of the people. Consequently, His Majesty commanded the Prime Minister to issue a directive to the 20 dzongkhags to elect one member each from every dzongkhag primarily or wholly for the purpose of drafting the constitution.

(Ugyen Penjore, 2008a, p. 5; emphasis mine)

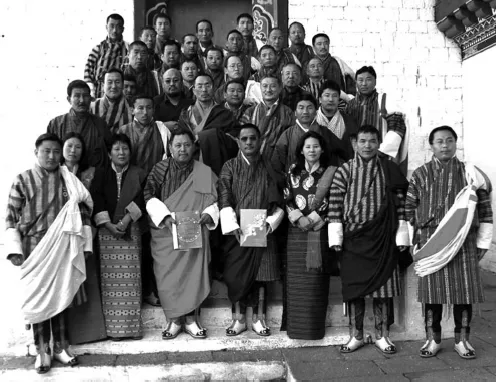

When the drafting of the Constitution was initiated on 20 November 2001 in Tashichho Dzong, the seat of the Bhutanese state, there were 39 members. Among them, there were 13 representatives from the government, three from the judiciary, two from the monastic community and 27 from the people. Among the representatives of the people were a member each from the 20 districts, who were elected by the respective DYTs. In addition, there were six councillors, who were elected members of RAC. Each councillor represented a group of districts. The councillors were also members of the former Assembly.

Figure 1.1 Members of the Constitution Drafting Committee

The composition of the drafting committee was, therefore, intended to constitute a popular body. With representations from the government and the monastic community, it became broad-based. Such representations have been the hallmark of popular institutions like the RAC and the earlier Assembly. However, it is important to note that the drafting committee was not a legislative body and, therefore, had no authority to promulgate the Constitution. Its broad-based composition nevertheless suggested that the Constitution was drafted by the representatives of the people.

The second important element in reinforcing the idea of the people as the source of legitimacy for the Constitution was the distribution of its copies on 26 March 2005 to members of GYTs and DYTs, civil servants, members of the judiciary, educational institutions, municipal corporations and the business community. Basically, every household in the country was provided a copy each. This was to set the stage for kingdom-wide public consultations later. King Jigme Singye Wangchuck began the nation-wide consultation process in Thimphu on 29 October 2005.

Later, the Crown Prince (the present King) continued the consultations, which ended on 4 May 2006 in Trongsa. In every public consultation, the people echoed concern over the introduction of parliamentary democracy. In his National Day address on 17 December 2005, the Fourth King said, “During my consultations on the Constitution in different districts, the main concern of the people is that it is too early to introduce parliamentary democracy in Bhutan” (His Majesty’s National Day Address a, 2005, p. 3). The King and Crown Prince conveyed to the people during the consultations that it was not at all early. Rather, they said the time was right to venture on historic political reforms. Although the people expressed concerns on the political transition that was being initiated, they made suggestions or raised objections on different clauses of the draft Constitution as discussions on its provisions proceeded during these public consultations.

The other important means of legitimising the Constitution through popular participation was the idea of holding a national referendum.

His Majesty pointed out that the draft Constitution was not submitted to the National Assembly first because the people might not accept the decision of the Assembly as there would be only 100 chimis representing the dzongkhags. The Constitution of Bhutan would, therefore, be adopted by referendum, as has been the practice in Bhutan for all important issues, and then enacted in the National Assembly.

(Kinley Dorji, 2005. pp. 1, 12; emphasis mine)

The referendum, however, was not held. Nor was the Constitution enacted in the Assembly. Rather, the public consultations came to be regarded later as a kind of national referendum. The concern was that the people may not endorse the Constitution and hence, parliamentary democracy, if a national referendum were held. Lyonpo Sonam Tobgye shared with me that the possibility of people rejecting the draft Constitution in a national referendum looked very real that it was later decided the process be foregone. Similarly, it was felt that the former Assembly would turn down the Constitution. Both these would be a major setback for the King’s initiative to democratise Bhutan. Some members asked that the draft Constitution and Election Bill be tabled for discussions in its final session of June 2007. The Chief Election Commissioner (CEC), however, refused to do so arguing that in the absence of the two houses of parliament, which would be elected in 2008, only the King was the legitimate authority at that point of time to endorse or reject the provisions of the Constitution and the Election and National Referendum Bills.

Figure 1.2 HRH The Trongsa Penlop consulting the people on the draft Constitution

The idea that the Constitution has popular legitimacy was reasserted when it was finally signed and promulgated on 18 July 2008. The King said that the Constitution had been placed before the people of the 20 districts. “Each word has earned its place with the blessings of every citizen in our nation. This is the People’s Constitution” (His Majesty’s Address at the Signing of the Constitution, 2008).

The popular view, nevertheless, continues to present the Constitution and parliamentary democracy as gift from the King. When the draft Constitution was distributed to the people on 26 March 2005, representatives of various institutions and organisations received copies of the draft Constitution from the chairman of the drafting committee. Wrapped in colourful silken cloth, the ceremony of distributing it was like that of granting a gift.

The chairman said:

This constitution was given by the head of the state, the King of Bhutan, who enjoyed the absolute confidence of the people. This is truly unique in the sense of the Buddhist principle of detachment … The people of Bhutan did not want the Constitution, but His Majesty in his wisdom felt that it was necessary to have one for the benefit of our posterity.

(Ugyen Penjore, 2008a, p. 5)

The chairman shared his thoughts that parliamentarians should not think of amending the Constitution in the near future.5 Once someone starts the amendment process, he was concerned that others would follow suit, and this may open doors for any ruling party in future to amend the Constitution as it deems fit to realise narrow short-term political goals. He shared his view that this Constitution must be in force without amendment for at least 50 years from now and that its letter and spirit must be given time and space for expression.

Lyonpo Khandu Wangchuk, the outgoing prime minister6 had also said that democracy was a gift from the golden throne to the people (Ugyen Penjore, 2007a, p. 13). Similarly, the then opposition leader, who served as the prime minister after the second parliamentary elections, had always maintained that the Constitution should not be discussed but promulgated intact. “Like most Bhutanese I see the Constitution as a precious gift from a monarch to his people, unparalleled and unprecedented in the world” (Tashi Wangmo, 2008b, p. 16). The idea of Constitution and democracy as gift was also articulated by the first prime minister, when he was on his familiarisation tours in different constituencies before formal campaigning for the last election began:

Beware of those that come to buy your vote. Your vote is a “Norbu Rinpoche,” a precious gem, a once in a lifetime gift. His Majesty the fourth King has given you each a precious gift, with the hope that you will use it wisely.

(Kencho Wangdi, 2007, p. 1; emphasis mine)

The discourse on Constitution and democracy as gift of the King did not take birth within the immediate context of introducing parliamentary democracy. Parliamentary elections of 2008 were preceded by 55 years of democratisation process, of which 34 years were largely characterised by decentralisation. Hence the people’s idea of Constitution as their King’s gift is in fact, a re-articulation of similar discourse surrounding political reforms he initiated during his reign.