With stinted stomachs and blistered feet, they carry their swags Out Back.

It is both a simple and yet a loaded question: “What is an Australian man?” Rife with conflicts and tensions concerning identity, race, and culture, it is perhaps difficult to determine what it means to be Australian, and male, in contemporary Australian culture. However, it is perhaps an easier task to identify what an Australian male should be, as idolised in both historical and contemporary culture. By should be, I mean the representation of a singular national masculine identity in which men are expected to aspire to, rather than attempt to homogenise, the multiplicity of masculine tropes within Australian culture.

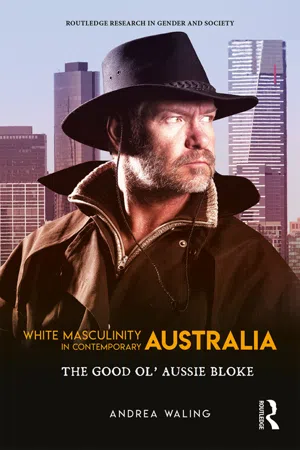

Historically, Australian (White) masculinity has been characterised by a particular set of qualities, traits, and behaviours that have become dominant Australian tropes. In this chapter, I outline the development of the singular Australian masculine trope: a White, working-class, Australian male who is typified by his loyalty, his able-bodiedness, his belief in and practice of mateship and egalitarianism (the notion that everyone is equal and should have fair access to equal rights and resources), his hard-working ethic, and his pride in being Australian. This will be done by providing a chronological historical account of the Australian cultural context in which this trope has emerged. Of course, it is prudent to recognise that there are multiple tropes of masculinity available throughout the history of Australian culture. My purpose here is to highlight and reflect on the trope that has remained as a singular national characterisation, re-embodied and manifested into new iconic ideals as time has worn on. As such, while I recognise the multiplicity of masculinity, and, indeed, the absence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and other cultural accounts and experiences, the purpose of this chapter is to explore the White, Anglo character that has come to be expected to be reflective of the authentic or “true” Aussie bloke. This is not meant to be an attempt to render insignificant or invisible the diversity in masculinity narratives and experiences within Australia. Rather, it is a way to explore how the White, iconic ideal has continued to be representative both of Australian men and what it essentially means to be “Australian.”

Examinations of Australian men have been limited in so far as determining how iconic ideals have shaped and structured narratives of masculinity that are presented today, and to what extent broader social forces have influenced these constructs. Masculinity on a wider scale has been dissected and discussed by numerous theorists to varying degrees that generally problematises masculine structures (see Waling 2019 for a review), but there has yet to be a historical account of past conceptions of Australian identity and masculinity and how these conceptions relate to the lived experiences of contemporary, urban Australian men. The notion of an Australian male ideal evokes a powerful connection between identity, nationality, and masculinity, best summed up by Murrie’s account:

He is practical rather than theoretical, he values physical prowess rather than intellectual capabilities, and he is good in a crisis but otherwise laid-back. He is common and earthy, so he is intolerant of affectation and cultural pretensions; he is no wowser, uninhibited in the pleasures of drinking, swearing and gambling; he is independent and egalitarian, and is a hater of authority and a “knocker” of eminent people. This explicit rejection of individualism is echoed in his unswerving loyalty to his mates.

(Murrie 1998, 68)

As Murrie (1998, 71) suggests, this male typifies perceptions of the bush and the outback, where masculinity is structured by physical rather than intellectual attributes, the dismissal of femininity, and loyalty to one’s mates. Australian identity and masculinity are structured through the absent “other” (71). This description echoes the ideals of frontier masculinity that are quite prevalent in global representations of Australian identity and masculinity, but it does not necessarily speak a particular truth about the Australian male (71). Rather, it demonstrates the prevalence that this idea of this particular masculinity might have in contemporary life, irrespective of whether such men exist or not.

To comprehend what contemporary Australian identity and masculinity might entail, we must situate ourselves in past conceptions of Australian identity and masculinity and recognise what, if any, recurring themes exist to uphold these expressions and whether these themes still exist today.1 Drawing upon historical narratives of Australian identity and masculinity, I provide an account of the stereotypes that have existed since the British settlement of Australia, focusing on methods of communicating masculine ideologies as they have developed over the past 100 years. I not only look to scholarship, but also to imagery and literary representations as a way to contextualise how the Australian male is talked about and visualised in everyday discourse. It is important again to reiterate that this is an idealised notion of the Australian male, not necessarily an accurate representation of Australian men in colonial times. I begin by exploring the development and the romanticisation of the Australian bushman in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, followed by an analysis of the emergence of the ANZAC war hero and the temporary “death” of a strong masculinity after World War I. I then discuss: the rise of the surf lifesaver as a new icon to replace those of the ANZAC and the bushman from the late 1920s to the end of the 1930s; the re-establishment of the ANZAC spirit during World War II; and the link between colonial notions of manhood and masculine sporting identities.

Larrikins, bushrangers, and the Australian bush

To provide context regarding the emergence of the Australian male trope requires a brief consideration of Australian settlement. The first prominent stereotype, and possibly one of the most iconic, is the frontier bushman who emerged within the era of the settlement and colonisation of Australia before Federation in 1901. The Australian frontiersman has been idolised in bush mythology and poetry with many names, including the larrikin, the ocker, the swagman,2 and the bushranger. Although the exact origins of these stereotypes have been debated amongst various theorists and historians, many agree that the stereotype of the Australian male has strong roots within the initial stages of colonisation by the British Empire and the transportation of convicts (Murrie 1998, 65; Ward 1958, 25). The initial landing of the British was by James Cook in 1770, although several attempts were made in earlier decades by other European explorers. Official colonisation occurred eighteen years later, in which the deportation and the exploitation of convicts from Britain facilitated the preliminary settlement of Australia. Part of this colonisation process included the slaughter of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia, and many political, economic, and religious rebellions (Macintyre 1999, 40). The transportation of convicts made up the majority of the earlier White populations of Australia, and these convicts and their children provided the hard labour necessary for gold mines when Australia’s gold rush occurred between 1851 and 1900.

It was during this time that a notion of an “Australian masculinity” first took hold, where Australia began the development of its independence. This masculinity was significantly different from its European counterparts, a direct result of its development within a much harsher and unforgiving landscape than that of the English countryside. The Victorian qualities of dandyism – a political, social, and cultural movement in the nineteenth century that emphasised fashion and leisure for middle-class men in an attempt to reclaim a more refined and aristocratic lifestyle popular in England (see Moers 1960; Murrie 1998) – was not suitable for the rough topography of the Australian bush (Ward 1958, 67). The geographic location of displaced British men required a new masculinity that could face and overcome the challenges that early frontier life and bush life presented (Ward 1958, 67). Mythmaking became an essential component to this process of recreating a masculinity that was fluent with the landscape (Bell 2003; Donoghue and Tranter 2015; Lee 1988). The “Australian legend” as termed by Russell Ward (1958) (i.e., the iconic Australian male) was born within this era, a man who worked in the Australian bush and was typified by certain characteristics that were identifiably “Australian.” Historians like Ward (1958) argue that notions of authentic Australian manhood arose from convict origins, and this is where the bushman ethos, an ideology concerning such notions of an “Australian masculinity,” is said to have been born. Ward (1958, 68) argues that the hardships of convict life gave early settler men the predisposition needed to cope with the unforgiving conditions of frontier life, often due to the lack of available resources, the rough topography of the environment, and the harsh climate. Political and social institutions were in their early days of establishment while the labour was hard and unforgiving in the dry heat of Australia (Ward 1958). Unlike the free immigrants who would have recently made the voyage, convicts were established within the Australian colony and were characterised by their hard bodies and hard ways of living: “their hands horny with toil; their faces tanned and tawny; their bodies seemed compounds of iron and leather. Hard workers they were, and hard drinkers” (Howitt 1845, quoted in Ward 1958, 68). These descriptions then translated into the physical construct of the frontier bushman depicted today. For Ward (1958), these men embodied (and/or represented) idealised notions of the openness of the outback and the opportunities for freedom it represented, in which only a masculinity that embodied strength and bravery could overcome the challenges it presented. Ward draws on Darwin’s theory of evolution to describe the bush as conducting “a natural selection upon the human material. The qualities favouring successful assimilation were adaptability, toughness, endurance, activity and loyalty to one’s fellows” – traits that are also closely associated with notions of mateship,3 Whiteness, and able-bodiedness.

Scholars like Lawson (1980) contest Ward’s conception of the origins of the Australian male, arguing that the Australian legend is a misrepresented and an inaccurate portrayal of the development of the bushman ethos. For Lawson (1980), origins of the Australian legend are found not in the Australian bush in the 1850s (as Ward claims) but in mid-nineteenth-century to early twentieth-century English literary sources. Moreover, there was no real tradition of mateship during the convict era, nor amongst the shearers later in the nineteenth century, but only amongst the miners during the gold rush of Victoria and New South Wales in 1850s (Lawson 1980, 578). As Lawson (1980, 579) maintains, Ward’s work should not be tested against the way Australians are but against the way in which they like to conceive of themselves – a more difficult task. This is because Ward is concerned with the typical rather than the average male frontiersman, bush worker, or Australian: the attitudes, beliefs, and values of the “legend” are admired and viewed as ideal, but were not necessarily practised (Lawson 1980, 579). Although Lawson makes a number of valid points, what Ward’s book illustrates is the prevalence of a stereotype, and it is this stereotype with which I am concerned. While Ward (1958) may set up his understanding of the Australian legend as based in true experiences (convict origins), which for Lawson (1980) is a romanticisation of a trope occurring much later during the mid-nineteenth up until the early twentieth century, both pinpoint to this notion of an ideal, singular “Australian masculinity.”

Literature and romanticising the bushman ethos

The end of the nineteenth century brought to Australia the greatest technological advancements of the Industrial Revolution, and with it came the Victorian doctrine of behaviour and dress, as well as an abundance of Australian literature, poetry, and art. At this point, Australia had been colonised for ninety-two years. There was a need to create, promote, and maintain a national identity that represented Australia, and this identity would be one of masculine character. An Australian identity was needed to further separate Australian society from British dandyism after Federation, so urban intellectuals sought to idolise men of the bush as quintessentially Australian and dismiss women as too fragile and vulnerable for the harsh conditions of bush life. A hero of Australia was needed, and this hero was an Australian male. Literature and art were the first methods used to communicate the ideals of the iconic Australian male.

Literary “representation confirms the existence of a useable past and this past is a prerequisite for the culture and civilisation of contemporary life” (Lee 1988, 56). The Australian male has been romanticised within writings and art of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century poets, novelists, and painters. Themes of Australian identity and an authentic Australian culture become apparent “through the selection of themes which become associated with the national identity” (Schaffer 1989, 115). In the early frontier times, the Australian bush was understood to be a place of hardship, challenges, and survival (see Figure 1.1). It was not a place to be sought after as romantic and idealistic (Harper 2000, 288).

However, in the late nineteenth century, the bush transformed from a place of unknown fear and destitution into an aesthetic paradise that the intellectuals of urban Australia wrote of in a manner such that it became fantasised and idolised for its connection to leisure, romance, and memories of boyhood (Harper 2000, 288). “Australian masculinity” was written as something to be revered and achieved, such as in the works of C. E. W. Bean (1879–1968), Aus...