![]()

Part I

Drawing genera

![]()

1 Footprint plans

Among architectural drawings, the plan is primary. Vitruvius lists the plan first in ancient architectural design and for modern architecture; Le Corbusier asserts that ‘the plan is the generator’.1 The plan gives its name metonymically to the entire design effort, and to all architectural drawings, as a set of plans. The plan is fundamental; but this is not to say that the plan is necessarily developed prior to any other drawings or that it determines the design. The plan is primary because it defines the core relation between drafter and drawing table by acknowledging the foundational nature of building in a particular place.

Architectural plans already had a significant practical and mythical status in ancient times. One of the oldest extant ground plans was created about 2200 BCE in Mesopotamia. In a life-size stone sculpture, the steward-king Gudea, ruler of the city-state of Lagash (in present day Iraq), is seated with a tablet resting on his lap that has an architectural plan inscribed upon it (see Figures 1.1a–b).2 The dedication text on the sculpture explains that it is to be placed in a temple built by Gudea and dedicated to the supreme god Ningirsu. The plan probably depicts the wall around his shrine, resembling the Mesopotamian clay brick architecture of thick walls reinforced with buttresses. Since this statue shows the prince as the architect of the temple, it certainly is an indicator of the primacy of the plan as a representation of a divine description of the temple that is given precedence over any other sort of image. A stylus sits on the right side of the tablet, as if just set down by Gudea, suggesting that his making of the plan was part of the divinely inspired ritual activity of the kingly architect.3 The prince sits facing his god for eternity to transmit messages as a living statue. Through a ritual transformation, the statue – described not as having been made, but rather ‘born in heaven’ – was animated to manifest the presence of the king. In its lengthy inscription, the statue speaks of how it is to be offered food and drink, washed, and dressed with clothing and jewelry.4 In this context, the plan’s presence on the sculpture defining the god’s sacred precinct on Earth demonstrates the plan’s importance as a ritual, as much as information for building.

Figure 1.1 a. Statue of Gudea, architect with plan (c. 2200 bce). Louvre, Paris. © RMN-Grand Palais, Art Resource, New York. Photo by René-Gabriel Ojeda. b. Detail of drawing tablet, architect with plan. Louvre, Paris. © RMN-Grand Palais, Art Resource, New York. Photo by René-Gabriel Ojeda.

Architectural ground plans with practical and ritual aspects also appear in ancient Egypt. There are more than twenty surviving Egyptian building plans related to construction or surveying work with written dimensions. Many are drawn on stone slabs or chips, some on wooden boards, and a few on papyrus.5 Imhotep, scribe and architect of the stepped pyramid, built an early temple at Edfu based upon ‘the great ground plan in the book which fell from heaven north of Memphis’.6 Important plans are often provided by the gods. This movement from sky to earth, like an architect’s design from idea to material building, emphasizes the important condition of a plan descending and impressing onto the ground.

Changing plans

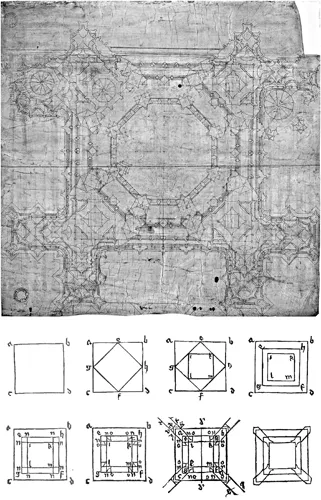

While the architectural plan is an enduring form of representation that has been in use across more than four millennia, characterizing all these simply as ‘plans’ fuels the erroneous but pervasive assumption that plans are all alike. Ideas of plans have changed substantially over time. Those accustomed to contemporary plans would have difficulty using late Gothic-era plans that commonly superimpose multiple layers and floors simultaneously. A 1467 plan of the north tower of St. Stephen’s Cathedral, Vienna by architect Lorenz Spenning, shows every adjustment in wall outline from the porch to the upper octagon. One historian counted 26 distinct levels on the tower plan (see Figure 1.2a).7 The finely crafted drawing shows traces of its geometric construction, and the wooden spire construction above the stone tower is marked, but uninked. This layered approach to plans is not an attempt to save on drawing material; it is a conscious design practice.

Figure 1.2 a. Lorenz Spenning, plan of north tower of St. Stephen’s Cathedral, Vienna (1467). Black ink and construction lines on parchment. Graphic Collection of the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna. b. Development of a pinnacle plan shown in eight steps. After Mathes Roriczer, Büchlein von der Fialen Gerechtigkeit (1486).

In the Middle Ages, rather than turn to Vitruvius, architects found their primary inspiration in the geometer Euclid (see Figure 1.7).8 The construction of a plan drawing followed a series of steps, each geometrical operation building upon the previous one like a geometrical proof. This is evident in the widespread medieval design drawing practice of ‘quadrature’, where a square rotated 45 degrees within another square generates design proportions for numerous elements from cloister and tower to window jamb. The Booklet Concerning Pinnacle Correctness, a late-Gothic (1486) German handbook illustrates eight progressive steps in developing the plan of a pinnacle (see Figure 1.2b).9 The plan showing every geometrical manipulation over the entire height of a tower records the geometric demonstrations in proper sequence with compass and rule. Thus, the sophisticated medieval plan has a limited relation to a modern plan. Although architectural plans in general have persisted over the millennia, notions of ‘plan’ change over time.

While some still assume that drawing came late to architecture after the Gothic era, this is an old fallacy living on only through its repetition.10 The number of known ancient and medieval architectural drawings has greatly increased in recent decades, so that even though many must have been lost to time, there is unassailable evidence of continuing design drawing practices.11 It is very difficult to comprehend how any major building could be created that requires the acquisition of enormous quantities of materials and the coordination of large numbers of people working together without some sort of design planning through drawing. Since there is evidence of plans throughout recorded history, it seems far more reasonable to conclude that drawing has been in use as long as there has been monumental architecture.

Horizontal section plans

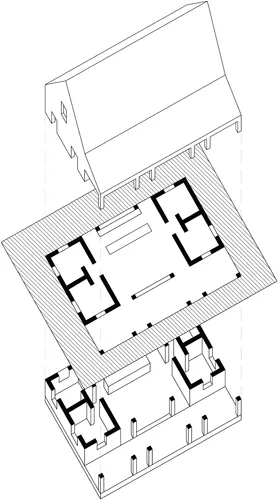

Today, plans are defined as horizontal sections. Francis D.K. Ching, in one of the most widely known twentieth-century student handbooks on architectural drawing, explains that plans and sections are ‘both sections or cuts: the plan is cut horizontally; the building section, vertically’ (see Figure 1.3).12 Similar definitions appear in virtually any handbook on architectural drawing beginning in the nineteenth century. Although presented as inevitable fact, this definition has a particular history with significant implications.

Figure 1.3 Floor plan as a horizontal section, explained as if made from an imprint from construction completed to a continuous height. After Francis Ching, Architectural Graphics, 4th ed (John Wiley & Sons, 2003) 39.

Jacques-Nicolas-Louis Durand (1760–1834) introduces the idea of plan as a horizontal section. Durand taught architecture to military cadets at the École Polytechnique (established in 1794) in Paris and summarized his course in Précis of the Lectures on Architecture (1802–1805), which through many editions had an enormous influence on architectural education.13 Emphasizing two principles of economy and utility, Durand promoted an early reductive functionalism, the goal of which is creating the most usable space for the least cost.14 Durand, defining the plan as a ‘building’s horizontal arrangement’, considered the floor plan as the most important drawing because of its close relation to utility and places it first in the ‘natural order’ of architectural drawings directing that ‘a design should begin with the plan’.15 Durand’s textbook remained in widespread use, without significant updates or competitors, for over 40 years. Léonce Reynaud (1803–1880), Durand’s student and later his successor at the École Polytechnique, wrote explicitly that the ‘plan will be a horizontal section of the building’.16 Joseph Gwilt, who translated much of Durand’s Précis into English in editions of the Encyclopedia of Architecture from 1840 and 1864, defines the plan of a projected edifice as a horizontal section.17 When Julien Guadet published an architectural textbook for his lectures at the École des Beaux-Arts at the beginning of the twentieth century, it again largely restated Durand’s approach:

The plan is a slice or section through a building on a horizontal plane which cuts through the walls, piers, partitions, etc., at a variable height. We assume the plane to be cutting at a convenient height to show all the details of construction, walls, doors and windows, piers, columns or pilasters, chimneys, etc. You can consider the plan as an imprint, taken on a flat surface, when the structure has all reached the same level in the height of a story.18

Durand’s view of plan remains dominant today, independent of stylistic penchants.

Durand’s approach to architectural drawing derives from descriptive geometry theorized by mathematician Gaspard Monge (1746–1...