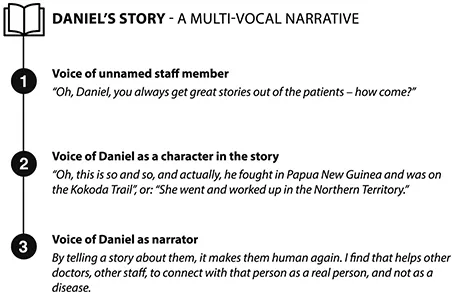

People often say to me, ‘Oh, Daniel, you always get great stories out of the patients – how come?’ So, when I’m handing over, I’ll say: ‘Oh this is so and so, and actually, he fought in Papua New Guinea and was on the Kokoda Trail’, or: ‘She went and worked up in the Northern Territory’, or something like that. By telling a story about them, it makes them human again. I find that helps other doctors, other staff, to connect with that person as a real person, and not as a disease.

Daniel, emergency physician and clinical teacher

Background

Throughout my 35 years in medical practice, I have been both intrigued and troubled by the relationships between doctors and patients. This book, based on my own research, takes a close look at encounters between hospital patients and medical students in their first clinical year. As newcomers to the hospital, medical students offer novel perspectives on the clinical encounters that happen there. My research also explores patients’ experiences of interacting with students and clinical teachers. Patient stories about being involved in clinical teaching have received limited attention in the literature, but offer important insights. The voices of clinical teachers are also relevant because they are key players in many interactions between students and patients.

In this book I explore identity in medical education as a dynamic, relational phenomenon, offering a fresh perspective informed by social theory and anthropological research. One of the ways people construct and perform identities in everyday life is through interactive storytelling. Medical educators appreciate that understanding and supporting the development of learners’ professional identity is as important as advancing their knowledge and skills (Goldie, 2012; Cruess, Cruess, Boudreau, Snell, & Steinert, 2014; Monrouxe, 2010). It is less widely recognised that identity construction is an integral part of all clinical teaching and learning.

Narrative, storytelling and identity

Language plays a central role in identity construction and performance, although non-verbal means also contribute. The clothes we wear and the way we physically interact with others, for example, can communicate a great deal about who we are (Iedema & Caldas-Coulthard, 2008, p. 6). In this book, my focus is mainly on the use of language, both because of my interest in storytelling and because my data consists mainly of verbal records of interviews and other encounters. The terms narrative and story sometimes convey different meanings, although I often use them interchangeably in this book as nouns, while I also use narrative as an adjective. One distinction I make is that some narratives arise and circulate as part of the cultures with which people identify. These shared narratives are a resource we draw upon to construct our own personal stories (Frank, 2010).

Researchers in the human sciences have a strong interest in stories, recognising them as objects for study in their own right, and not merely as vehicles for the transmission of data (Garro & Mattingly, 2000; Bleakley, 2005). An appreciation of the power of storytelling can be linked in the Western world to an enduring fascination with language, autobiography and the self (Reissman, 2008). Storytelling is a way of bringing together the worlds of action and consciousness, and making meaning from experience (Garro & Mattingly, 2000). Stories can be understood as actors in the social world because they can make things happen by influencing those who hear them (Frank, 2010).

A story is an account with certain characteristics, including a description of events in which something happens as a result of a previous event. In a fully developed story, a pattern or narrative arc is usually followed: the scene is set, an unexpected or troubling event occurs, and suspense develops as to how it will be resolved. After the resolution, the narrator offers an evaluation of characters and events (Frank, 2010). There is a consequential relationship between events in even the simplest story. Most of the stories in this book were produced through interactive talk. In these situations, a story may be quite short and lack some of these elements (Gubrium & Holstein, 2009).

Narrators always select and organise their story’s component parts to suit their intended audiences. In other words, a story is always recipient-designed, whether this is done deliberately or not (Frank, 2010; Reissman, 2008). The way we transcribe recordings of interviews and other interactions can influence the stories that emerge from that data. For this project, interactions were transcribed word for word as far as possible, noting the tone or volume of a speaker’s voice, any hesitation or laughter and including my contributions as the interviewer. This approach allows a deeper understanding of the context in which a story was told and provides access to the small story fragments that populate people’s conversations (Sools, 2013).

Stories serve many purposes. Autobiographical stories can help us understand the past, as lived experiences are given form and evaluated by narrators, often in collaboration with others. This is a key process in psychotherapy and in many research settings. Stories can also shape the future, because the insights gained from telling or listening to a story can influence people’s actions (Garro & Mattingly, 2000). Crucially for this project, they convey something about the character or identity of the narrator and characters in the story, and often persuade us to interpret events from the narrator’s perspective (Frank, 2010).

Narrative and identity are linked in the concept of master narratives: stories told and authorised by powerful or higher status groups within a society (Nelson, 2001). Master narratives identify members of less powerful or lower status social groups in particular ways. The persistence of these stories can constrain the identities that those depicted in them are able to construct for themselves, and consequently the ways in which they can act in the world. However, they may construct counter-stories, resisting the identities imposed upon them by those in more powerful positions. This illustrates how the rhetorical or persuasive functions of a story can be used for political as well as social ends (Garro & Mattingly, 2000; Nelson, 2001).

While I highlight the important relationship between storytelling and identity, I acknowledge the argument that some people do not perceive their lives as having a narrative quality. Strawson (2004) argues that it is possible to flourish and live an ethically good life without thinking narratively. This argument seems to be based on the idea of narrative as the story of a person’s life, with a recognisable narrative structure. In contrast, I am interested in the small story fragments from everyday human interactions. These may be considered autobiographical in that they contain stories from or about the narrator’s life, but they need not be integrated into a coherent whole. Besides, not all stories are well-structured – indeed, some illness narratives have a chaotic quality, and their lack of coherence can express their narrators’ bewildering experience more eloquently than the words from which they are composed (Middlebrook, 1996; Rimmon-Kenan, 2002; De Peuter, 1998).

During my fieldwork I often discussed with students their encounters with patients. Many students wondered why their attempts to elicit the history of a patient’s illness often resulted in long, rambling stories. When I examined these stories closely, I realised that they accomplish much more than just the transmission of facts. Whenever someone tells a story, they also convey something about who they are in relation to others. This identity work takes place whenever people interact with each other. In a teaching hospital, this can include patients, doctors, nurses, allied health professionals, family members and housekeeping staff as well as students. In this book, I focus on encounters between medical students and patients, which often involve doctors as well in a teaching or supervisory capacity.

Aims

I have several aims in writing this book. The first is to show how students and patients use interactive storytelling to construct identities in relation to each other. Identity work is an integral part of all learning interactions. When clinical teachers recognise that identity work is taking place, they can encourage learners to reflect about it. Gaining insight into the struggles associated with identity formation may help educators to support medical students and doctors-in-training through times of conflict or distress (Dyrbye, Thomas, & Shanafelt, 2005; Monrouxe, 2010).

Secondly, I want to demonstrate why paying attention to patients’ stories in medical education is important, even when they seem irrelevant to the presenting problem. These stories may offer insights into patients’ experiences of participating in clinical teaching, which can be positive, negative or mixed. Clinical teachers who appreciate this are better placed to reduce the likelihood of discomfort or harm to patients and maximise the potential for benefit (Chretien, Goldman, Craven, & Faselis, 2010; Nair, Coughlan, & Hensley, 1997; Rice, 2008). In this book, I use stories to explore the inter-relationship between identity, power dynamics and ethics in clinical teaching and learning interactions. This offers insights into how patients are recruited for clinical teaching, and how some common practices can compromise the validity of their consent to participate.

Finally, I will show how appreciating the importance of storytelling can humanise the practice of clinical teaching and care. A patient becomes a unique individual when they are given space to tell stories about their life, and again when these self-identifying stories are shared with other people. Without them, a person can be perceived as just another case of some condition. Storytelling opens a window into patients’ lives and helps students and clinicians relate to them with empathy and compassion.

Outline of theory and methods

A detailed explanation of my research methods and supporting theory can be found in Chapter 2. This brief outline shows how my research relates to the published work discussed later in this chapter. The theoretical foundation for the study on which this book is based is the work of Mikhail Bakhtin, a Russian theorist and literary critic who proposed that human relations are best understood as a dialogue (Gardiner & Bell, 1998). By this he meant that people construct selves – analogous to identities – in relation to the people they interact with, and that this process involves a creative struggle (Holquist, 2002). Bakhtin’s ideas influenced social theorist and psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva, who proposed the idea of the self as dynamic and constantly changing (Guberman, 1996). Like Bakhtin, Kristeva highlights negotiation and struggle as essential to identity construction.

I used an ethnographic approach to study medical student and patient encounters in a large metropolitan teaching hospital in Australia. I was interested in how medical students and patients experience and interpret their interactions with each other in a teaching hospital. Ethnographic researchers spend extended periods of time, often months or years, engaged in the practice of fieldwork. This involves immersion in the everyday life of a cultural group, collecting stories through observations and interactions, including interviews and informal conversations.

After obtaining approval from the relevant ethics committees, I recruited three groups of participants: students in their first clinical year, patients and clinical teachers. I gathered stories from observations of clinical teaching interactions and undertook in-depth, semi-structured interviews. After repeated reading of the transcribed data and listening to the audio recordings, I constructed tables and charts highlighting important stories and drawing links between them. I observed emerging themes and connections, and selected stories for deeper analysis that were most salient to my research focus, as well as those that were surprising or especially moving.

I analysed these stories using a process called dialogic narrative analysis, focusing on how a story was produced and performed within a particular context (Gubrium & Holstein, 2009; Reissman, 2008). I incorporated elements of critical discourse analysis, enabling meanings to emerge from the way a story was told as well as its content. This involved looking closely at how language was used within a story to convey context-specific meanings. I identified multiple voices used by a single narrator and juxtaposed stories told by different narrators, placing them in dialogue with each other. Finally, I considered what had been accomplished by telling a given story in a particular context (Frank, 2010).