As preliminary steps we shall first try to determine the corresponding terms in Latin, Greek and Arabic sources and to decide the date of the duana baronum’s appearance.6

A. Corresponding terms (Latin, Greek and Arabic)

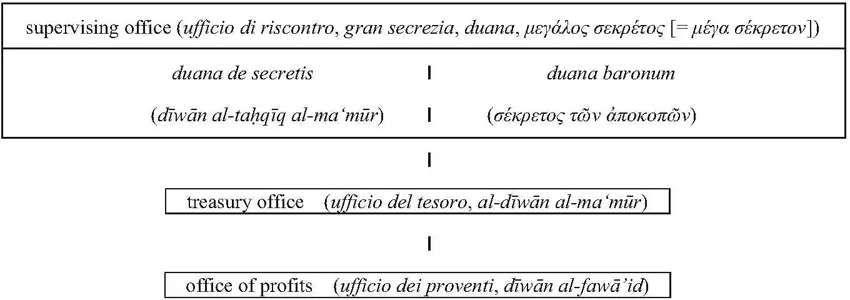

In this section we shall fix the Greek and Arabic corresponding to the most essential Latin terms: duana de secretis, duana baronum, magister duane de secretis, and magister duane baronum (see Figure 1.2).

First let us compare Latin and Greek documents of 1180. These differ a little in details but have the same content:

[Latin] Geoffrey of Modica (Goffridus de moac), palatinus camerarius and magister regie duane de secretis et duane baronum, (send) greeting and love to all baiuli and portulani of Sicily, Calabria, and the principality of Salerno, that is, his friends to whom this letter will be shown.7

[Greek] Geoffrey of Modica (ἰοσφρὲς τῆς μοδάκ), ho epi tou megalou sekretou kai sekretou tōn apokopōn (ὁ ἐπὶ τοῦ μεγάλου σεκρέτου καὶ ἐπὶ τοῦ σεκρέτου τῶν ἀποκοπῶν) and ho palatinos kapriliggas (ὁ παλατῖνος καπριλίγγας), [send] greetings to all exousiastai (ἐξουσιασταί) and parathalattioi (παραθαλάττιοι) of Sicily, Calabria, and the principality of Salerno, that is, his friends reading this letter.8

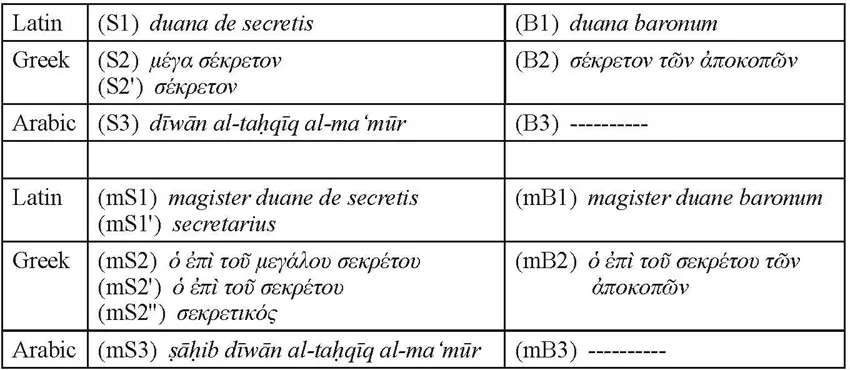

We find close correspondence of Latin to Greek. Magister regie duane de secretis et duane baronum corresponds to ho epi tou megalou sekretou kai sekretou tōn apokopōn (ὁ ἐπὶ τοῦ μεγάλου σεκρέτου καὶ ἐπὶ τοῦ σεκρέτου τῶν ἀποκοπῶν). So, (mS1) magister duane de secretis corresponds to (mS2) ho epi tou megalou sekretou (ὁ ἐπὶ τοῦ μεγάλου σεκρέτου) and (mB1) magister duane baronum to (mB2) ho epi tou sekretou tōn apokopōn (ὁ ἐπὶ τοῦ σεκρέτου τῶν ἀποκοπῶν). Therefore, (S1) duana de secretis corresponds to (S2) mega sekreton (μέγα σέκρετον) and (B1) duana baronum to (B2) sekreton tōn apokopōn (σέκρετον τῶν ἀποκοπῶν). For the Arabic correspondents, our source is a Latin document translated in 1286 from the Arabic of 1175:

[Latin] and Sanson baiulus in the Marrani River presented the document of the dohana mamur, that is, doana secreti including the declaration of the aforesaid division (divisa), and was read in the presence of these aforementioned Christians and Saracens who knew the names of these places… and confirmation was firmly made among them on what was said in the presence of Shaikh Bicca’ib magister doane de secretis which is called in Arabic duén tahki’k elmama. This is doana veritatis in the aforesaid old times.9

We are able to establish that (S1) duana de secretis corresponds to (S3) dīwān al-taḥqīq al-ma‘mūr (duén tahki’k elmama in this document). But we cannot verify the relation of (S1) duana de secretis and (*) al-dīwān al-ma‘mūr (dohana mamur in the document).

Figure 1.2 Corresponding terms I (Latin, Greek and Arabic)

Our next sources are Greek and Arabic documents of 1161. They have the same general contents but slightly differing styles of expression:

[Greek] Martin, Matthew, and other gerontes (γέροντες), that is, ho epi tou sekretou (οἱ ἐπὶ τοῦ σεκρέτου) who confirm this document below admit the following.10

[Arabic] This is the writing in which they recorded what Ya‘qūb b. Faḍlūn b. Sāliḥ had bought from al-shaikh al-qā’id Martin, al-shaikh al-qā’id Matthew and al-shuyūkh who are aṣḥāb dīwān al-taḥqīq al-ma‘mūr.11

In these, (mS2) ho epi tou sekretou (οἱ ἐπὶ τοῦ σεκρέτου) corresponds to (mS3) aṣḥāb dīwān al-taḥqīq al-ma‘mūr. Therefore (S2) sekreton (σέκρετον) corresponds to (S3) dīwān al-taḥqīq al-ma‘mūr. Here one should note the terms gerōn (γέρων, pl. γέροντες) and shaikh (pl. shuyūkh). These are not official posts but only titles of honor. They mean something like “elders.”12

The aforementioned terms are the only exact correspondents that we can verify. We can ascertain further information from bilingual sources. In documents of October 1172, a certain Geoffrey was called iosphres ho sekretikos (ἰοσφρὲς ὁ σεκρετικός) in Greek and al-shaikh Jāfrāy ṣāḥib dīwān al-taḥqīq al-ma‘mūr in Arabic.13 (mS2’) sekretikos (σεκρετικός) corresponds to (mS3) ṣāḥib dīwān al-taḥqīq al-ma‘mūr. Similarly, in documents of February 1172 the same Geoffrey was called domini gaufridi secretarii in Latin and τοῦ σεκρετικοῦ κυροῦ ἰοσφρὲ in Greek.14 (mS2’) σεκρετικός corresponds to (mS1’) secretarius. These are rough but not exact correspondences, however.

In summary, one can arrange the correspondent words in order as in Figure 1.3.15

B. Date of the duana baronum ’s appearance

Figure 1.3 Corresponding terms II (Latin, Greek and Arabic)

Caravale says of the duana baronum, “This office appears for the first time in two sources of 1174.”16 Mazzarese Fardella states, “We desire to emphasize that the duana baronum is documented only since 1174 and that, therefore, we should examine what competence the duana de secretis had had before this date.”17 Jamison also suggests the year 1174.18 Is it certain, however, that the duana baronum had not existed before 1174?

We have established in the former section that the term duana de secretis corresponds to μέγα σέκρετον or σέκρετον and dīwān al-taḥqīq al-ma‘mūr, and the term duana baronum to σέκρετον τῶν ἀποκοπῶν. Why does the duana de secretis have two Greek names, μέγα σέκρετον and σέκρετον? That is to say, why was the magister duane de secretis called ὁ ἐπὶ τοῦ σεκρέτου in January 1161 and November 1167, though he was entitled ὁ ἐπὶ τοῦ μεγάλου σεκρέτου in 1180?19 The reason must be that the office corresponding to σέκρετον was originally the duana de secretis, but that when another σέκρετον, that is, the duana baronum, appeared, one had to call the duana de secretis as μέγα σέκρετον to distinguish it from the other σέκρετον.20 Therefore, to find the date of the duana baronum’s appearance, we must search for the date when the expression μέγα σέκρετον began to be used. Μέγα σέκρετον appeared for the first time in a document of October 1170: