Misunderstanding 1: ‘sustainability is about ecological concerns’

Of course, sustainability is about ecological issues, but that’s only one part of the story. In particular in industrialised societies, the discussion about sustainability tends to be narrowed down to the ecological domain, while the challenge lies essentially in how we can develop societies that provide a high quality of life in a way that is simultaneously ecological and just, not only locally or nationally, but also globally. In fact, this was already part of the most influential definition of sustainable development, namely the one dating from the report Our Common Future, published in 1987 by the United Nations (UN). This so-called Brundt-land Report defines sustainable development as ‘a development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (WCED 1987, 8). Meeting needs obviously does not only refer to a clean environment, but also to food, housing, education and so on. This interpretation of sustainability as implying both the social and ecological domain has been reaffirmed in 2017 in the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that were approved by the UN (2017). The SDGs cover a broad spectrum of environmental, social, economic and institutional goals.

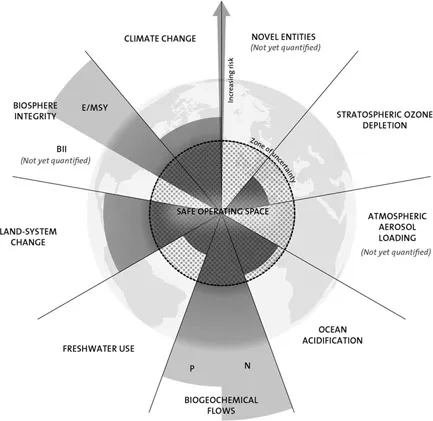

So what does it mean that the challenge of sustainability lies essentially in the combination of social and ecological goals? We start by briefly discussing them separately. One of the most influential interpretations of the ecological challenge derives from Rockström et al. (2009), who introduced the planetary boundary concept, which defines the environmental limits within which humanity can safely operate. An updated analysis of this framework (Steffen et al. 2015) shows that four of nine planetary boundaries have now been crossed as a result of human activity: climate change, loss of biosphere integrity, land-system change and altered biogeochemical cycles (see Figure 1.1) These four exceedances also have a pervasive influence on the remaining boundaries.

Figure 1.1 Estimates of how the different control variables for seven planetary boundaries have changed from 1950 to present

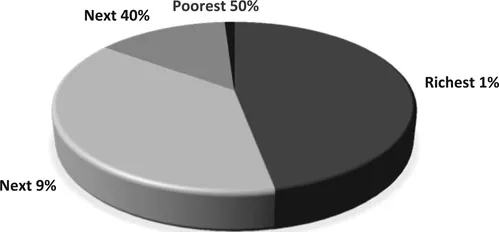

What about the social side of sustainability? While the number of people living in extreme poverty dropped by more than half between 1999 and 2013 – from 1.7 billion to 767 million (UN 2017) – too many are still struggling for the most basic human needs such as food, water, shelter, education and health care. Moreover, authors such as Wilkinson and Pickett (2009), Piketty (2014) and Alvaredo et al. (2018) have documented the growth of inequality and have shown that income inequality has increased in nearly all world regions in recent decades. According to the Credit Suisse Research Institute (2018) and as shown in Figure 1.2, the richest decile (top 10% of adults) owns 85% of global wealth, and the globe’s richest 1% owns almost half the world’s wealth, while the bottom half collectively owns less than 1% of total wealth.

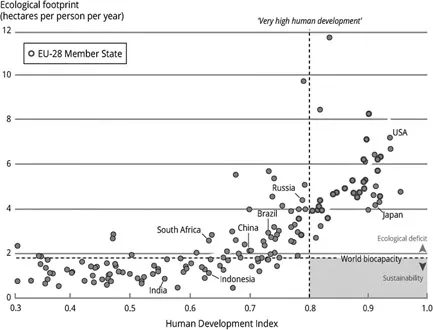

Such social and ecological concerns are challenging in themselves, but a typical characteristic of sustainable development lies in the combination of the two. Sustainability is about ecological and social concerns at the same time. An interesting way to assess sustainability is, for instance, by combining the ecological footprint (EF) for the ecological concerns with the human development index (HDI) for the social concerns. The EF relates to the impact of human activities measured in terms of the area of biologically productive land and water required to produce the goods consumed and to assimilate the wastes generated. An EF of less than 1.7 global hectares (gha) per person makes the resource demands globally replicable (this is sometimes called ‘the fair earth share’), but the average per capita is currently 2.7 gha per person. So the average EF per person worldwide needs to fall significantly, especially in Northern countries where the EF is often higher than 7 gha per person. The human development index is an index that measures key dimensions of human development: life expectancy, years of schooling and gross domestic product per capita. The UN considers an HDI over 0.8 to be ‘very high human development’. With these two thresholds, we can define two minimum criteria for global sustainable development, namely an average EF lower than 1.7 gha per person and an HDI of at least 0.8. Figure 1.3 shows that only a few countries come close to achieving sustainability in this definition.

Figure 1.2 Division of global wealth

This figure also makes clear what the main sustainability challenges are: (1) for countries in the left lower corner: creating a high level of human development without depleting the planet’s or a region’s ecological resource base, and (2) for countries in the upper right corner: creating a lower ecological footprint while retaining high human development. This global idea of sustainability as a combination of quality of life, ecological limits and justice can also be used to define the rough contours of sustainability within a country, a city, a neighbourhood, a project, a course, etc.

Figure 1.3 Correlation of ecological footprint and the human development index

Misunderstanding 2: ‘we need a waterproof and objective definition of sustainability’

A fixed definition of sustainability ignores the political character and the custom-made approach this guiding concept requires. Even the oft-cited definition from the Brundtland Report (see above), or another regularly cited definition such as the one of Agyeman et al. (2003, 5), i.e. ‘the need to ensure a better quality of life for all, now and into the future, in a just and equitable manner, whilst living within the limits of supporting ecosystems’, make clear that ‘sustainability’ is based upon normative principles such as needs, equity and ecological limits that cannot be unequivocally defined. Instead, the sustainability concept is shaped, used and ‘owned’ by an ever-widening range of stakeholders (Hopwood et al. 2005). This democratisation of sustainability is a positive evolution as it testifies to the power of attraction and the enduring relevance of the concept (Hugé et al. 2016). But a consequence is that the diversity of stakeholders engaging with sustainability (e.g. academics, governments, business, NGOs) gives rise to a multitude of interpretations, because actors try to produce interpretations that favour their interests.

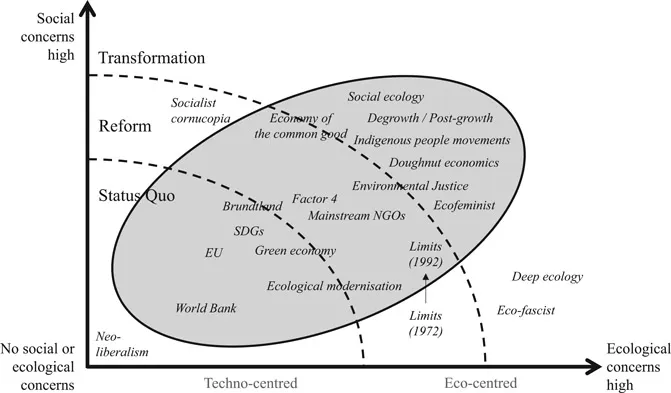

Inspired by an article of Hopwood et al. (2005) of 14 years ago, we mapped different interpretations of sustainable development (see Figure 1.4). Hopwood et al. use a socio-economic and an environmental axis to distinguish between three views on the nature and scope of change, ranging from status quo to reform-ist to transformation.

Figure 1.4 Mapping of views on sustainable development

Views in the status quo band aspire to a belief in ‘business as usual’: sustainability can be achieved within existing political structures and economic growth models. Growth provides resources to pay for environmental measures and technologies, and ‘trickle-down economics’ will solve the poverty problems (as in this view economic benefits for the wealthy will trickle down to the poorer members of society). This perspective counts on eco-efficiency, international competitiveness and free markets (Hopwood et al. 2005). The challenge essentially lies in finding the right combination of technologies to meet rising demands in sustainable ways. Within status quo approaches the market is often the agent of transformation, through which pricing, creating markets and property rights regimes unleash new rounds of ‘green accumulation’ (Scoones et al. 2015). Reformist models are critical of current policies of governments and business, but they still believe that sustainability problems can be solved within the current political and economic structures. Green economists support capitalism, but give the government an important role (Hopwood et al. 2005). The starting point is often the need to re-embed (global) markets in stronger frameworks of social control, combined with a recognition of the state’s historically central role in previous waves of innovation and financing of technology and growth (Scoones et al. 2015). According to transformative approaches, a fundamental change is needed because sustainability problems ‘are located within the very economic and power structures of society’ and in ‘how humans interrelate with the environment’ (Hopwood et al. 2005, 45). Therefore, approaches such as degrowth or doughnut economics postulate that besides eco-efficiency, also sufficiency, redistribution and decommodification are essential sustainability strategies (D’Alisa et al. 2014). Transformative approaches suggest that transformations often arise from political action of groups outside the centres of power (indigenous groups, women, the poor and working class).

Over the years, the mainstream of the debate – mainly carried by UN organisations, national governments, the EU, World Bank, international NGOs, etc. – has been a mixture of the status quo view and the reform view (Hopwood et al. 2005; Paredis 2013). This fits perfectly within the idea of ecological modernisation, an approach that argues that the capitalist economy benefits from moves towards environmentalism. Through a smart interaction of technology, science, business and markets, with a government that intervenes by setting standards and providing incentives through market mechanisms, ecological modernisation promises a ‘positive-sum game’, where economic growth and ecological protection can be combined (Hajer 1995; Paredis 2013).

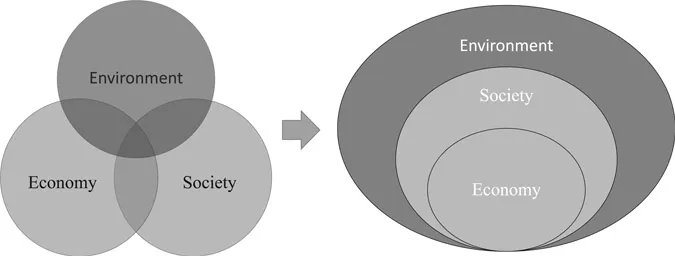

As stated in the introduction, we argue that the diversity of interpretations is a consequence of the political character of the concept of sustainability. But does that mean that all interpretations are of equal merit? Although we do not advocate a fixed definition of sustainability, neither are we in favour of ‘anything-goes’ relativism. For us, the concept of sustainability opens up a space to think beyond status quo views, and as such beyond the ideas of ‘technological fix’ and ‘trickle-down economics’. In this respect, we propose to use the nested model to visualise the essence of sustainability and not the iconic figure of the triple bottom line (see Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5 From the iconic figure of the triple bottom line (left) towards the nested hierarchy model (right)

The triple bottom line, also expressed in the phrase ‘people, planet and profit’, considers ‘business’ and ‘profit’ as goals in itself, next to social and ecological challenges, and focuses on the mutual maximisation of the three dimensions. The win-win assumption behind this model neglects the obvious link between current economic activities and planetary environmental degradation (Isil and Hernke 2017) or the growth of inequality. The nested hierarchy model applies a logic from ecological economics that takes as its basis a socially discussed ecological scale which subsequently determines the contours of a fair distribution and only then leaves room for the market to determine how to realise an efficient allocation (Daly 1992; Martínez-Alier and Muradian 2015).

This plea for taking reform and transformative approaches seriously implies automatically a call for fundamental changes in societal structures, practices and ways of thinking. For understanding such changes, we appeal to transition studies, a discipline which is also confronted with some misunderstandings.