![]()

1 Surveying EU defence industrial policy

European defence industrial cooperation has been an important issue for many decades. In the Western European Union’s 1998 Rome Declaration the then member states acknowledged that Europe’s

operational potential cannot be realised without an adequate purpose-adapted European defence capacity and this in turn demands harmonisation of operational requirements and rationalisation of research and technology, development and procurement as well as of the industrial base in the field of armaments.

(Western European Union 1998: 3)

Even in the 1950s, Articles 107 and 109 of the failed Treaty for a European Defence Community referred to the need for European states to standardise and jointly procure defence equipment (Fursdon 1980: 163–162; Ruane 2000). In more recent times, former president of the European Council, Herman Van Rompuy, has surmised that greater cooperation is a way of strengthening Europe’s broader industrial and manufacturing base because it supports scientific ingenuity and a high-skilled labour force (European Council 2013a: 6). Bodies such as the European Defence Agency support this sentiment by working to ensure that Europe produces cutting-edge defence capabilities (European Defence Agency 2006a, 2007; European Council 2013a: 6). As the Agency’s 2007 EDTIB Strategy makes plain, if a strong European defence industrial base is to underpin the EU’s CSDP then Europe ‘cannot continue routinely to determine [its] equipment requirements on separate national bases, develop them through separate national R&D efforts, and realise them through separate national procurements’ (European Defence Agency 2007: 1).

More recently, the EU Global Strategy makes clear that strategic autonomy is a goal for EU defence and that the industrial elements of this autonomy require sustained EU support (2016: 45). This strategy has given rise to a number of defence industrial policy initiatives. For example, the member states have agreed to a Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD) which will see the EDA ensure greater synchronisation between the national defence planning processes of EU member states. The idea is for member state defence planners to share information on defence planning horizons and future technology/capability plans with the EDA in the hope that duplication can be avoided and future cooperative programmes can be defined. The hope is that CARD may lead to greater opportunities for capability development and defence research collaboration (Fiott 2017a).

Furthermore, in 2016 the European Commission established a European Defence Fund where it has committed €90 million for defence research until the end of 2019. This total is planned to rise to €500 million per year after 2020, making the European Commission the fourth largest investor in defence research in the EU when compared to the member states. Furthermore, under the fund the Commission has set aside €500 million over 2019 to 2020 to support the development of joint capability programmes in the EU, and after 2020 the Commission expects this total to rise to €1 billion per year (European Commission 2017). This initiative seeks to enhance European cooperation through the use of financial incentives. These incentives are designed to ensure that no financial support will be provided to the member states without first agreeing to standardise defence requirements at the beginning of a capability project and to develop these programmes in collaboration with two or more partner member states (De La Brosse 2017; Fiott 2017b).

One other notable initiative that emerged in December 2017 is the agreement between 25 EU member states to engage in Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO). As foreseen under the Lisbon Treaty, PESCO is designed as a political framework that should lead to the progressive framing of a common EU defence. PESCO is divided between two levels of cooperation. First, the participating member states – all EU states minus Denmark, Malta and the UK – agree to 20 binding commitments that are subject to a yearly review by the HR/VP (with support from the EDA and the EU Military Staff) that range from spending more on defence, enhancing European capability development to engaging with defence research endeavours. Second, the participating member states are involved in developing specific capability projects. In 2018, a first wave of 17 projects, including maritime surveillance, armoured vehicles, a medical command, etc. was agreed to with further project phases to be defined in the future. PESCO is designed to give a structured, political framework to European defence cooperation (Fiott, Missiroli and Tardy 2017; Biscop 2018).

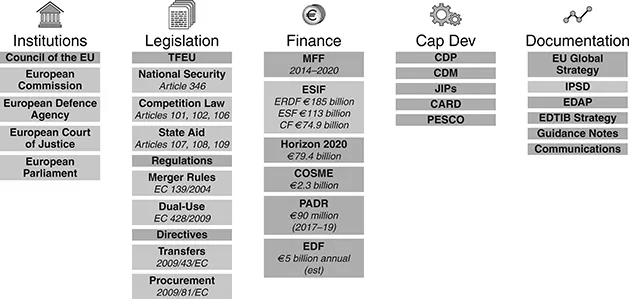

In the face of defence market fragmentation and greater global competition, these new initiatives combine with the examples of cooperation found in this book to form the basis for the EU’s defence industrial policy framework. The book opts for the notion of a ‘defence industrial policy framework’ (see Figure 1.1 below) instead of the often-used ‘EDTIB’ because the EDTIB is a contested concept.1 Instead, this book focuses on law and regulation, capability development programmes, financing mechanisms and policy initiatives. This chapter in turn raises some of the challenges associated with national preference formation and interdependence in the European defence sector. Accordingly, this chapter takes stock of how the balancing of market openness and autarky, economic health and military strength and sovereignty and cooperation plays out in a European context. This chapter is consequently divided into four main sections that look consecutively at the constituent parts of the European defence industrial policy framework.

Law and regulation

The most developed element of the EU’s defence industrial policy framework is law and regulation, or, to be more precise, EU primary and secondary law. No other defence industrial cooperative framework in Europe – not the LoI, OCCAR or NATO – embodies a legal framework such as that found at the EU level. Not only do the EU treaties frame questions about national sovereignty, defence and industry in an EU context but the European Commission plays an important role in upholding key elements of legislation that relate to the defence sector. For its part, the ECJ serves as a mediator in disputes involving the member states, firms and the Commission. The European Parliament, as a co-legislator with the Council of the EU, plays an important role in amending and agreeing to defence-relevant EU secondary law such as the ‘defence package’. EU law is an important, albeit limited, mechanism through which to coerce the member states into adhering to laws that are aimed at liberalising the European defence market (Blauberger and Weiss 2013). The laws and regulations that underpin the EU’s internal market are a way to break down barriers between national defence markets and to enhance cross-border trade in defence equipment, while also pushing regulation to the EU level. As Trybus remarks, ‘[w]hile this Internal Market or “Community” regulation and policy cannot be considered a complete success [it has] established a viable legal framework for the operation of the Internal Market’ in the defence sector (2014: 222).

This is a familiar facet of European market integration. Hix and Goetz (2000) observe that the European Commission has traditionally supported a process of market liberalisation at the EU level. As they remark, ‘the EU is a deregulatory project. The removal of technical, fiscal and physical barriers to the “free movement” of goods, services, capital and labour in the single market programme’ has led to ‘considerable deregulation and liberalisation of domestic markets’ (ibid.: 4). While the drive towards more market liberalisation cannot be disputed, even in the defence sector, it is worth reflecting on the tools required to achieve greater liberalisation in Europe’s defence markets. Regulation – that is, regulation at the EU rather than the national level – is a vital part of the liberalisation process (McGowan and Wallace 1996; Majone 1997; Damro 2012: 687). Thus, whereas the European Commission has pledged ‘to further develop the Internal Market for defence’ it can only do this via regulation that tackles persistent ‘unfair and discriminatory practices and market distortions’ (European Commission 2013a: 10). The European Commission favours the simultaneous liberalisation of economic activities in the internal market and greater EU-level regulation. While market liberalisation is a way to dismantle barriers to trade within the internal market, regulation at the EU level is defined as the ‘promulgation of an authoritative set of rules, accompanied by some mechanism for monitoring and promoting compliance with those rules’ (Levi-Faur 2008: 103).

In many ways, the liberalisation/regulation agenda is to be expected, given that ‘supranational agents are characterised by a common preference for greater competences for themselves and for the European Union as a whole’ (Pollack 2003: 39). Yet, the European Commission does not have a free hand in its quest for a more liberalised and regulated EU defence market. There are several factors hindering a greater regulatory role for the Commission in the European defence market. First, given the European Commission’s responsibilities for a range of defence-relevant areas such as competition law, research policy, industrial policy, internal market, etc., it should not be assumed that each directorate general2 (DG) is enthusiastic about gaining greater competences over the defence sector – especially for those DGs with an overwhelmingly civilian focus such as research policy (Mörth 2000). Second, the European Commission finds it difficult to establish links with Europe’s defence firms because these firms still overwhelmingly deal with national governments – after all, governments offer procurement contracts and the Commission does not. As one official from the European Commission confirmed, ‘unfortunately we still only have an indirect and partial link with the defence industry’.3

The European Commission’s role in the formulation of defence industrial policy is therefore limited to a ‘structural approach’ that can be defined as the undertaking of initiatives that are designed to shape the internal market in defence via an emphasis on market regulation and competition. As the European Commission itself recognises, the best framework through which ‘to implement structural change’ in the European defence market is to use its regulatory, internal market-based, powers (European Commission 2013a: 8). The European Commission’s policy approach to European defence industrial policy is conditioned by its own mandate, which emanates mainly from EU primary and secondary law, and institutional form, because it is a supranational institution without automatic links to the defence industry or powers over national defence industrial decision-making. Confined to a specific mandate based on its position as the legal custodian of EU Treaties, the European Commission is, for now at least, largely restricted to its regulatory powers in the field of arms cooperation (Trybus 2006: 673; Britz 2010: 178; Calleja-Crespo and Delsaux 2012: 6; Hoeffler 2012).

Figure 1.1 The EU Defence Industrial Policy Framework.

Source: author’s own.

Nevertheless, the role played by EU law and regulation in driving defence market liberalisation and enhancing EU-level regulation has long been a key element of the European Commission’s strategy for the EDTIB. The Commission’s own steps to create an effective European Defence Equipment Market (EDEM) reflect its desire to see an ‘homogenous defence economy framework’ in which the civil, internal security and military market spheres are gradually brought together to form an integrated dual-use market (Schmitt 2005a: 10–11; Aalto 2008: 39). The idea for an EDEM gained particular traction in the 1990s and the policy concept was seen as a vehicle for market liberalisation based on the principles of the EU internal market and EU law (i.e. the free movement of goods and services, open public procurement, etc.). The ethos under the EDEM was that defence market liberalisation could be achieved through market regulation; in particular, the free flow of goods and services would eventually lower the cost of defence for European states. It is important to recognise the nuanced difference in meaning between the EDEM and the EDTIB, even though the two concepts are used interchangeably in policy and academic literature.

Whereas the EDEM referred more specifically to market liberalisation and defence equipment, the EDTIB addressed more strategically salient factors such as defence research, security of supply and equipment standardisation. Whereas the EDEM was mainly focused on reducing the barriers and costs associated with intra-EU cross-border cooperation, the EDTIB concept went one step further by channelling efforts towards improving the operational autonomy of EU member states and ensuring that Europe’s defence industrial base could survive and prosper over the longer term. In this regard, the ‘EDTIB Strategy’ of 2007 broadens the ter...