![]()

1 Neutrality of money1

The Cantillon effect constitutes an important argument in the debate on the neutrality of money. Before I get into the details, I want to explain what the economists mean when they say that money is neutral. This will provide the necessary context for the proper understanding of the first-round effect.

In broad terms, neutrality of money means that monetary phenomena have no impact on real variables. The question of whether money is neutral – and if not, in what way does it affect the real sphere – is one of the central economic issues that every school of economic thought must address. Monetary phenomena, however, may be viewed from different perspectives, which leads to the existence of diverse concepts of money neutrality. Therefore, before we begin discussing neutrality of money, we should define it more precisely. Neutrality of money may be understood as a situation in which the existence of money has no effect on the functioning of the economy, or in which the volume of money has no effect on the real prosperity, or in which changes in money supply during the transition period do not impact the real economic variables, or in which varied pace of changes in money supply does not impact the sphere of real economy, or as a situation in which neither surplus demand for money nor surplus supply appear. Those meanings are shown in Table 1.1 – let’s analyze them now and prove that economists often wrongly color conclusions from one concept of neutrality with conclusions from another concept.

Table 1.1 Types of money neutrality

| Types of money neutrality | Impact |

| Institutional neutrality | The existence of money does not impact the functioning of economy |

| Static neutrality | Quantity of money does not impact real prosperity |

| Dynamic neutrality | Changes in money supply do not impact real economic variables |

| Super-neutrality | Changes in the pace of increasing money supply do not impact real economic variables |

| Monetary neutrality | Existence of equilibrium on the money market, expressed as the MV constant (quantity of money in circulation multiplied by the speed of circulation) |

Source: Author’s compilation

Institutional neutrality2

According to the first view, neutrality of money is defined as a situation in which monetary economy behaves like barter economy.3 In other words, in this definition money “is merely a ‘veil’ that can be removed and relative prices can be analyzed, as if the system was based on natural exchange” (Lange, 1961). Barter market, due to its supposed lack of “frictions”, is a standard benchmark used for analyzing the impact of monetary factors on economy (Hayek, 1935, pp. 130–1). The problem with this view is that barter economy in actuality experiences great frictions – that being one of the reasons which inclined people to begin using money, because it makes trading much quicker and more convenient. To put it another way, there is no sense in comparing monetary economy – which is something qualitatively different – to barter economy, as for the latter there would be no reason to use money if it were truly free of “frictions” (Visser, 2002).

Such approach, named by Schumpeter (2006) the real analysis (as opposed to monetary analysis), was common among classical and neoclassical economists, who maintained that there is so-called classical dichotomy, in which nominal variables can be analyzed completely separately from real variables. Therefore, they treated money merely as numéraire, impacting only the nominal prices, while the relative prices were – according to them – determined solely by real variables (Mill, 2009 [1848]).

Mises (1998 [1949], p. 203) describes such approach as follows:

The whole theory of catallactics, it was held, can be elaborated under the assumption that there is direct exchange only. If this is once achieved, the only thing to be added is the “simple” insertion of money terms into the complex of theorems concerning direct exchange.

In other words, researchers working in this tradition maintained that the introduction of money doesn’t change the economic reality in any way, other than making the exchange of goods easier to perform and that such exchanges will involve two separate transactions.4

The erroneous character of this thinking is largely due to the misconception of the nature of money5 and not appreciating that it is a good, the value of which is established the same way as with other goods or services. It isn’t merely a veil covering the real economy or “the great wheel of circulation” (Smith 1904 [1776]), but a good desired by the participants of the market for its usefulness in an uncertain world and for enabling economic calculations, which, in turn, lead to the creation of advanced economy.

What’s more, as a common means of exchange, money impacts all other markets. To put it another way, using the thought process of barter economy isn’t wrong in itself, and in some aspects of economy is indispensable; however, economists often draw erroneous conclusions based on this thought process, an example of which is the very concept of neutral money (Mises, 1998 [1949]).6

Static neutrality

The second view attributes neutrality to money from the perspective of comparative statics, meaning that social welfare depends not on the nominal amount of money in possession of an individual, but rather on the purchasing power of money – the amount of goods it can buy. According to Friedman (1969b), that is the essence of quantity theory of money. It is true that, historically speaking, John Locke created that theory (which says that increase in money supply leads only to an increase in prices) partly in response to the mercantile view, which stated that wealth is determined by the amount of bullion per se.7 The latter is obviously false, because “society is always in enjoyment of the maximum utility obtainable from the use of money” (Mises, 1953 [1912], p. 142).

That statement, however, will only be true within comparative statics. As Mises (1953 [1912], p. 145) continues:

If we compare two static economic systems, which differ in no way from one another except that in one there is twice as much money as in the other, it appears that the purchasing power of the monetary unit in the one system must be equal to half that of the monetary unit in the other. Nevertheless, we may not conclude from this that a doubling of the quantity of money must lead to a halving of the purchasing power of the monetary unit; for every variation in the quantity of money introduces a dynamic factor into the static economic system.

Unfortunately, many economists draw erroneous conclusions from comparative statics and argue that changes in money supply are neutral in the long term. As Blaug (1985, p. 19) accurately noticed, “this confusion between comparative statics and dynamics is one which we will encounter time and time again in the history of economic analysis.”

Dynamic neutrality

So far, I’ve talked about the concept of money neutrality from the perspective of statics. The first view assessed whether the mere existence of money led to any perturbations in the real world, the second assessed whether the amount of money in an economy actually matters. The third view – the one usually associated with neutrality of money – deals with variations in the supply of money,8 therefore conclusions drawn from the analysis of this concept are vital for monetary policy.

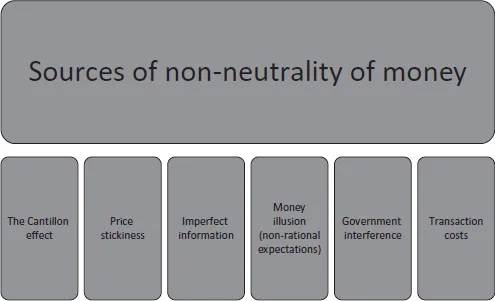

According to this view, money neutrality is achieved when any fluctuations in its supply result only in proportional changes in nominal values. Non-neutrality of money implies – obviously – the opposite case, or a situation in which changes in the supply of money impact real variables, such as production or employment. Non-neutrality of money is the consequence of several factors. The most important ones are shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Key factors in (dynamic) non-neutrality of money

Source: Author’s compilation

As may be clearly seen in Figure 1.1, in order for the changes in money supply to impact only nominal variables and nothing else, several conditions would have to be satisfied. First of all, the new money would have to simultaneously and proportionately increase the cash balances of all entities. That assumes the absence of the Cantillon effect, or the price-distribution effect resulting from the uneven changes in the money supply, therefore from the very fact that new money reaches the economy only through certain channels. However, with that effect, some people – those who were the first to receive new money – would be able to spend the newly acquired money in an environment in which prices haven’t changed yet. People further down the line in this “monetary food chain” – when this new money finally reached them – would be met with prices that had already been raised. As can be seen, irregular increases of money supply cause changes in the distribution of income and wealth, as well as changes in the relative price structure (prices of products purchased by the first beneficiaries of increased money supply increase in relation to the prices of products purchased by the later recipients of the new cash).

Second, people would have to be aware of the fact that, for instance, the money supply increased evenly and that now everybody has twice the amount of cash at their disposal. As an example, if sellers don’t anticipate that consumers will be able to commit twice as much money to purchase their goods, they won’t necessarily raise prices right away. Individuals would also need to know how the changes in money supply will affect prices. In other words, for the changes to affect only nominal values, everyone should be fully informed and have rational expectations. Take, for example, employees who consider the nominal increase of their paycheck as a real increase, which then inclines them to increase the amount of work they do. The outcomes of monetary illusion have been researched by monetarists. Similarly, if manufacturers take an increase in prices of their products as a relative price increase, without tying it to the increase in money supply caused by the arrival of Friedman’s helicopter, they may increase production. The outcomes of imperfect information – and the resulting “money surprise” – are dealt with by the new classical economics.

Third, all prices would have to change simultaneously, as is the case in Walras’ general equilibrium model. Otherwise, the relative price structure would change, which would impact allocation of supplies and production. So, what’s required is not only the so-called price rigidity, but also that everyone would try to spend their nominally increased cash balances at the same time and with identical elasticity of prices.9 Full price elasticity implies, among other things, that information about changes in money supply should be not only full, but also “retroactive”.10 In other words, in situations with long-term contracts, each unforeseen increase in money supply causes real changes. The significance of price rigidity in the adjustment process following monetary fluctuations is dealt with by the New Keynesian school.11

Fourth, it would be necessary to assume an unchanged expenditure structure of business entities. Therefore, in order to avoid any real effects, business entities would have to allocate the newly acquired funds in the same proportions as before not only for consumption and investments (including cash balances), but also for particular goods and services.

Fifth, for money to remain neutral in the situation described by Friedman (1969a), people would have to assume its unexpected gain to be a singular event (or that it will occur in predetermined periods and the volume of increase in money supply will be known). Otherwise, the uncertainty regarding the possible arrival of the helicopter might affect the cash balances of business entities and thus the real sphere of the economy. In other words, there would have to be no destabilizing expectations. As can be seen from the above examples, accurate predictions play an important role in the hypothesis of money neutrality; however for money to be neutral, business entities would have to know about not only the increases in money supply and the overall prices, but also the details of the money’s flow through the economy.12

Sixth, money neutrality may refer only to fiat money, currency without intrinsic value, which itself is not a traded commodity nor a claim to it (Zijp and Visser, 1994). This is obvious when you look at gold as money – if its supply increased, the buying power would decrease, thus diminishing the profitability of gold mines and increasing the use of the yellow bullion for non-monetary purposes, which in turn would impact the relative price structure.

The seventh condition, which may seem obvious, is the non-interference of government, such as price controls or sales quotas. Cantillon (1959 [1755]) recalls a ban on cattle imports to Great Britain and from that example concludes that if consumer demand increased in response to an increase in money supply, meat prices would rise relative to price of bread, as cheaper corn could still be imported from abroad to replace domestic grain that had been made more expensive due to inflation. Also, taxes – since they are calculated on nominal income – would have a significant impact on the fruition of the Cantillon effect. An obvious example is becoming subject to a higher tax rate due to a nominal incre...